Dan’s Stage 4 ALK+ Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Story

At 34, Dan was diagnosed with stage 4 ALK+ non-small cell lung cancer.

He shares the importance of patient advocacy, sharing your story and experiences, having doctors in your corner and willing to fight for you, and being honest and open with your children.

- Name: Dan W.

- Diagnosis:

- Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC)

- ALK+

- Staging: 4

- Symptoms:

- Cold symptoms

- Shortness of breath

- A little bit of tightness in the chest

- Loss of voice

- Course of Treatment:

- Stent placement

- Radiation

- Targeted therapy (Alectinib)

- Stent removal

- Radiation

- Targeted therapy

Being a dad is something that’s very special for me so I don’t think I took it for granted. I think it just has more meaning now being able to do those things

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Pre-diagnosis

Introduce yourself a little bit

I like to have a great time. I try to see [the] positivity in things, even before [my] cancer diagnosis. I try and get along with a lot of people. I really want to have positive interactions with people that I come across, whether it’s just meeting them for the first time or just saying hi to someone. [I’m] very loving and outgoing.

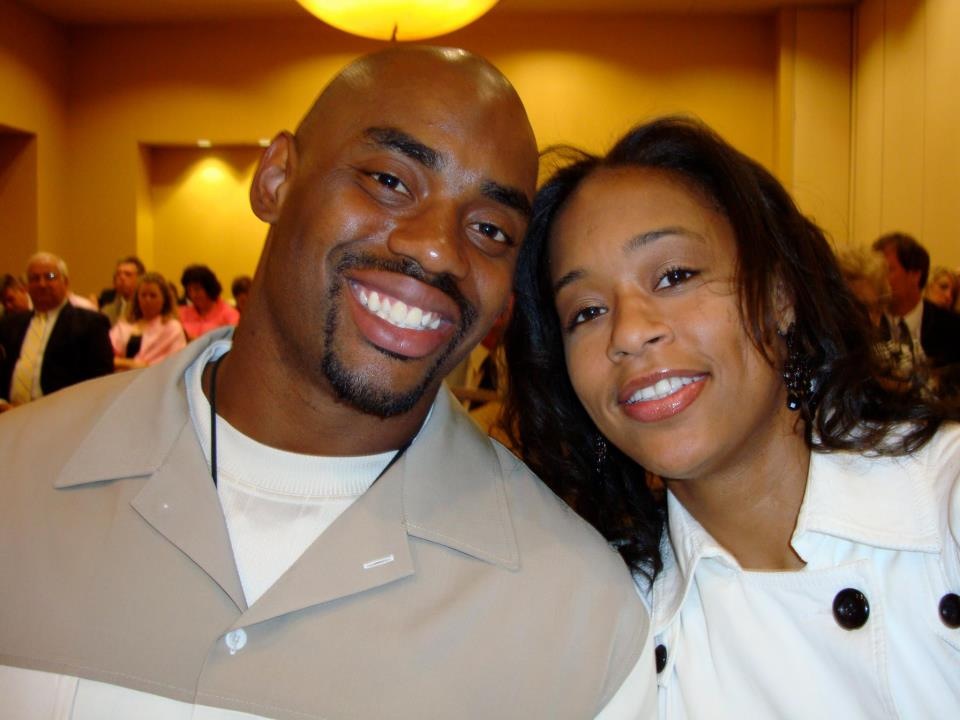

[I have a wife and] two daughters. Francesca is seven and Georgia is five. The oldest one is named after [my wife’s] grandmother and my grandfather and goes by the name of Frankie.

My oldest is very outgoing [and] has to have social interaction [on] any given day or any given time. She’s very much like me. Always has something to say. She’s been talking as long as she could get a word out. She’ll talk until she falls asleep every night.

Georgia is very shy. She just turned five. She likes to hide behind us and [have] us as a sense of security. But when she’s out with friends, family and people that she’s comfortable with, she’s just as outgoing as Frankie is, so it’s great to see that side of her personality come out when she gets comfortable with people.

It wasn’t until a CT scan was performed that they had come across a large mass in my chest.

Initial symptoms

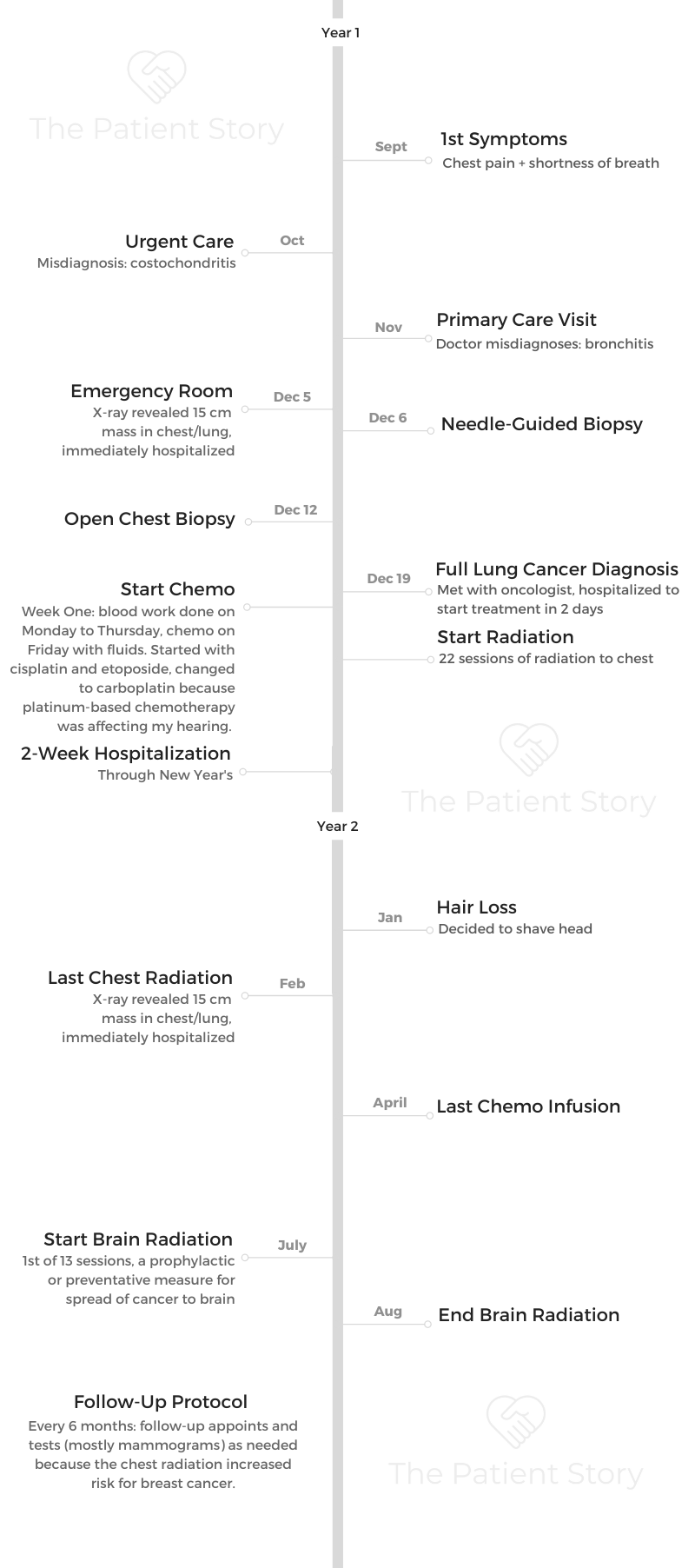

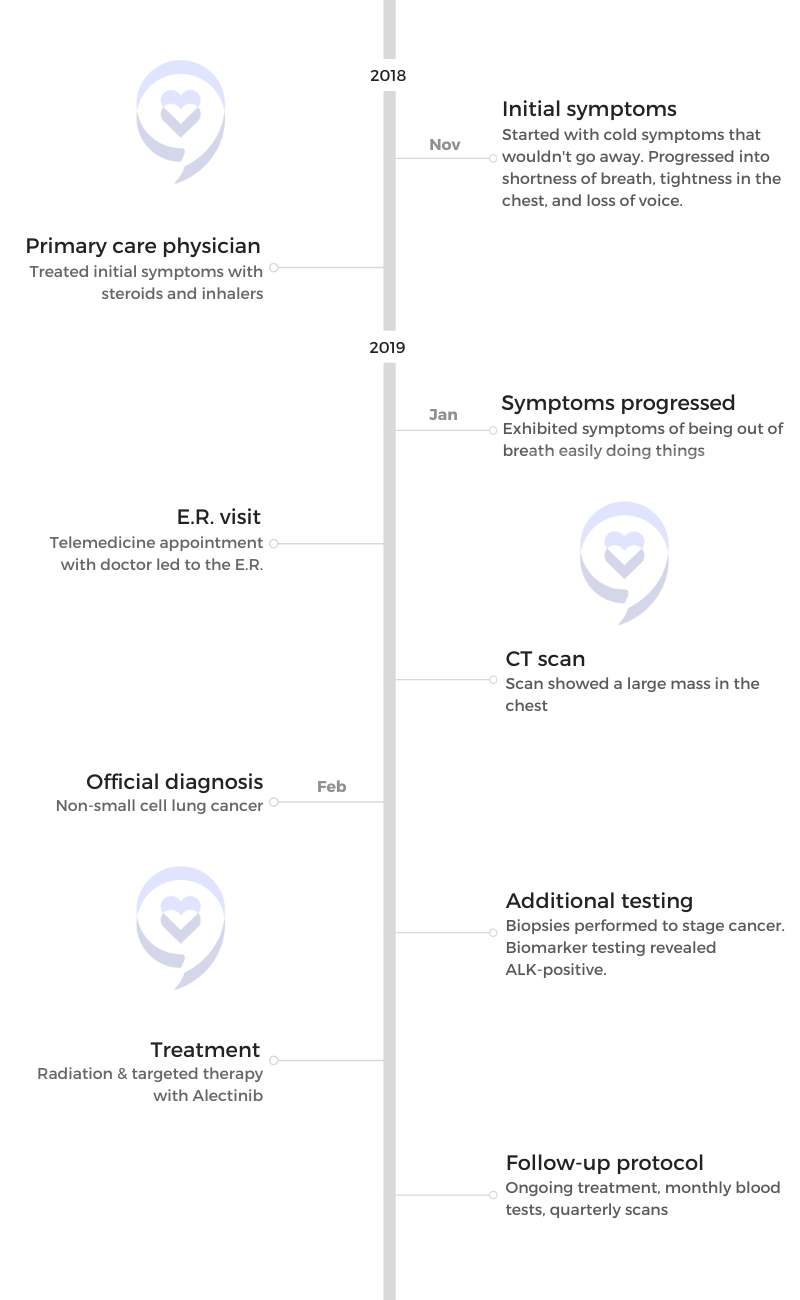

I started with cold symptoms about mid-November of 2018. Then the cold just wouldn’t go away. It progressed into shortness of breath, a little bit of tightness in the chest, [and loss of] my voice.

[I was] going to my primary care physician and just being pumped with steroids or inhalers — nothing seemed to work at any point and no additional tests were ordered. It was all the way until the very end of January [2019] that I was chasing my youngest across the dance studio and I was out of breath within steps. I had already exhibited symptoms of being out of breath easily doing other things, but I was always resilient to push through.

I had a telemedicine appointment and the doctor said, “You could have had a minor heart attack at some point. We need you to go to the E.R.” I went to the E.R. and a number of tests were done. It wasn’t until a CT scan was performed that they had come across a large mass in my chest.

Diagnosis

The doctor had come in to tell me, “You have a large mass in your chest. We’re pretty sure it’s cancer. And we think it’s lymphoma.”

My uncle had passed away from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma just after six months of being diagnosed back in the mid-2000s and the first thought that ran through my head [was] what his kids went through. Not necessarily him but what his family went through because of the diagnosis.

It struck home for me right away and I knew it was serious at that point.

Things really get real and put into perspective when someone throws around a cancer diagnosis.

Receiving the news

I didn’t go to the hospital until about 10:00 or 10:30 at night. It wasn’t until two, three o’clock in the morning that the doctor had actually come back into the room in the E.R. I was by myself not thinking that anything was going on [and] wasn’t really scared going to the hospital in any way.

My wife stayed home with our girls because, obviously, they couldn’t stay at home alone. At that point, I called my wife and we had a family member come over and watch the kids. Then my wife rushed over as soon as she could.

Thinking about your children

Children’s innocence was so prevalent in my mind at that point. The thought that they don’t know what cancer is, what it means… if they had to put their mind around something, it’s just probably going to be death associated with cancer.

The thought that my kids would grow up without a dad or without that influence in their life, it was really hurtful to me. Not that I ever took life for granted, but things really get real and put into perspective when someone throws around a cancer diagnosis.

How do I tell my children about my cancer diagnosis? »

They were four and two, so pretty extreme for them to hear that daddy has cancer.

Getting the official diagnosis

From the day that I went into the hospital, I would say 10 or 11 days later, we realized that it was non-small cell lung cancer. At that point, it was at least stage three and they were going to do some staging.

In the coming week or two, there were a number of different staging tests that I had gone through and biopsies to determine [if it was] stage three or stage four.

It was a snowy Tuesday. My wife, a school teacher, was home from school. I was working from home. We had received a phone call from the lymphoma oncologist as well as the interventional pulmonologist who had done the bronchoscopy to get the sample. They had given us three ideas of what it could have been — sarcoidosis, lymphoma, and lung cancer. We’re not expecting lung cancer, but here it is. We’re going to tell you it could be lung cancer, but we really don’t think it’s that.

When that Tuesday afternoon came and they called, they asked us to write some things down. Thankfully, my wife was home. They gave us the news that it was lung cancer; at that point, at least stage three. But I had a biomarker, a driver behind my cancer that was ALK-positive. We had no idea what that meant.

In a career that’s not medically related in any way and my wife being a teacher, we’re street smart at that point. She’s much more book smart than I am, but [we] immediately went to survival mode. Let’s start looking up what this means. Let’s see who to see in situations like this. Second opinions. Who do we go to? Who do we talk to? What are our resources and how do we navigate this new norm for us? Because, at this point, we didn’t know therapies, treatment, [or] what was going on in that initial diagnosis, so a lot of unknowns for us.

Reaction to the diagnosis

It’s kind of a blur, to be honest. There [are] so many vivid memories from a lot of the events that had taken place.

Your life is a whirlwind when you’re first diagnosed or when you’re going through some of those traumatic experiences [in] that you don’t remember everything. Some things stick out more than others, but I remember placing the call. I remember the doctor coming in, sitting on the bed, and saying that to me, but I don’t recall when she had come in.

I thought about my kids. Cancer sometimes runs in your family. Is this something that I can pass on to my kids? Is this genetic mutation something that would also be related to my brothers? I’m one of four. Do I need to have a conversation with them that they have to get screened?

What are my kids going to go through? I brought kids into this world not knowing much about cancer itself. Had I known before, would I still have brought kids into this world? Those were some of the thoughts that went through my mind.

[We] immediately went into survival mode… at this point, we didn’t know therapies, treatment, [or] what was going on in that initial diagnosis, so a lot of unknowns for us.

Later on, as I’m starting to additionally digest some of the information, it’s — How did I get lung cancer? Where did that come from? What have I done to expose myself to second-hand smoke? Not being a smoker or [having] a history of smoking myself, what environmental factors have I been exposed to where I’m susceptible at this point to lung cancer? [I] just couldn’t really hang my hat on anything specific.

The doctors assured us that from what they can tell, it’s not environmentally driven, but there’s a switch in your body, something went off. We don’t know what caused it, but we would say that would not be environmental.

It was a little troublesome to put myself in the position of looking at how that affected my kids and my family.

The more and more that we learn is crazy. The stories that we hear, the people that we follow, the people that we become connected with and friends with, being diagnosed at such a young age and then living a healthy lifestyle is completely difficult to fathom. At the end of the day, it just doesn’t make sense to us.

Patients share how they reacted to a cancer diagnosis »

Treatment

Radiation and targeted therapy

The plan was to radiate the largest mass in my chest, at the base of my mediastinum where it splits off to either lung. That would provide relief. Largest cancer site, let’s radiate it. [I] went through five sessions — Wednesday through Tuesday, [then] Saturday and Sunday off.

It wasn’t too bad. I’m pretty resilient so if I’m tired, I’m not necessarily realizing that I’m tired. I’m just pushing through things. Probably a good quality but, at the same time, probably a bad quality where you have to listen to your body and understand what it’s telling you at times.

Once radiation was done, we were starting [the] first-line treatment with targeted therapy. The idea with the targeted therapy was, hopefully, [my] quality of life would go back to where it was before and I’d be able to do the same things that I was doing with my kids, my wife, and in my personal time prior to cancer.

Find answers to popular radiation therapy questions and experiences of radiation therapy »

Undergoing radiation and targeted therapy again

Thankfully, living in the Northeast, [there are] two great hospital systems in Philadelphia. There [are] more than just two but I focused my care at two, [partnered] with some doctors in Boston, [and] continuously reviewed the plan [and] best course of treatment. How do we continue to move forward and be as successful as possible [in] navigating my diagnosis?

The idea was to do consolidated therapy. They were going to go to the right side of my lung — top and lower lobes — and radiate. They were going to radiate those sites with the idea that if progression does occur, it’s going to most likely go back to those original cancer sites. Since it wasn’t treated previously from radiation, they wanted to go back and just clean up those spots [and] make sure that there [weren’t] any residual cells there as well.

Find answers to popular targeted therapy questions and experiences of targeted therapy »

Importance of biomarker testing

Neither of us [has] a background in health care or in medicine so just what you see sensationalized on TV or if you have a family member or friend that’s going through something, that’s your exposure to it if it’s not part of your expertise.

Thankfully, we have access to great healthcare systems and that was the norm for them. We just said, “Hey, something’s not right.” And they said, “We’ll help you out. We’ll take the reigns from here and do what we’re supposed to do.”

Little did we know that meant biomarker testing and so on, but we’re thankful that that was done and identified very early on. Hearing other people’s stories, that’s not always the case.

Advocating for yourself

You hear nightmare stories where people just go straight to chemo and certain cocktails of treatment options that are used in lung cancer can be fatal for someone who is ALK-positive. Right then and there, knowing that you’re giving something to someone from a therapy standpoint that could actually kill them before it could even help them is troublesome.

It’s so difficult when you’re putting yourself out there and someone’s telling you that what they do for a living isn’t going to help you in any way.

You just have to advocate for yourself. We did early on not knowing what we were going into and what we were navigating at that point. But it was very important for us to pull together doctors that would be in our corner and would fight for us. It wasn’t about them. It was about us as patients.

We actually had not a great experience with the hospital that I went into when I was first experiencing symptoms. We left with the intention of never coming back.

We had an oncologist come into the room the day after I was admitted and just said very vague information, didn’t have much to give from an outlook standpoint or what was going on, or what he thought was going on.

When you go to the doctor and you break a bone, you’re used to looking at an X-ray, right? You’re expecting. We did a CT scan [so we were expecting], “We’re going to show you the CT scan, what we’re looking at, and what’s going on.” He said, “I don’t read pictures.” And we were like, “What do you mean? You’re an oncologist. How do you not?” “Oh, well, we have people that do that. I don’t.”

We lost a lot of hope right then and there for any proper guidance from him as an oncologist, even just from a general standpoint. We had asked them to leave. It was a very difficult situation for us. But, thankfully, [the] interventional pulmonologist followed up and came into the room a short period later and was able to explain some things to us as to what he was seeing and navigate those scans with us.

It’s so difficult when you’re putting yourself out there and someone’s telling you that what they do for a living isn’t going to help you in any way. You get very turned off. We left a few hours later from that hospital with the intention of never coming back there.

Hear from cancer patients on what self-advocacy is and how they advocated for themselves »

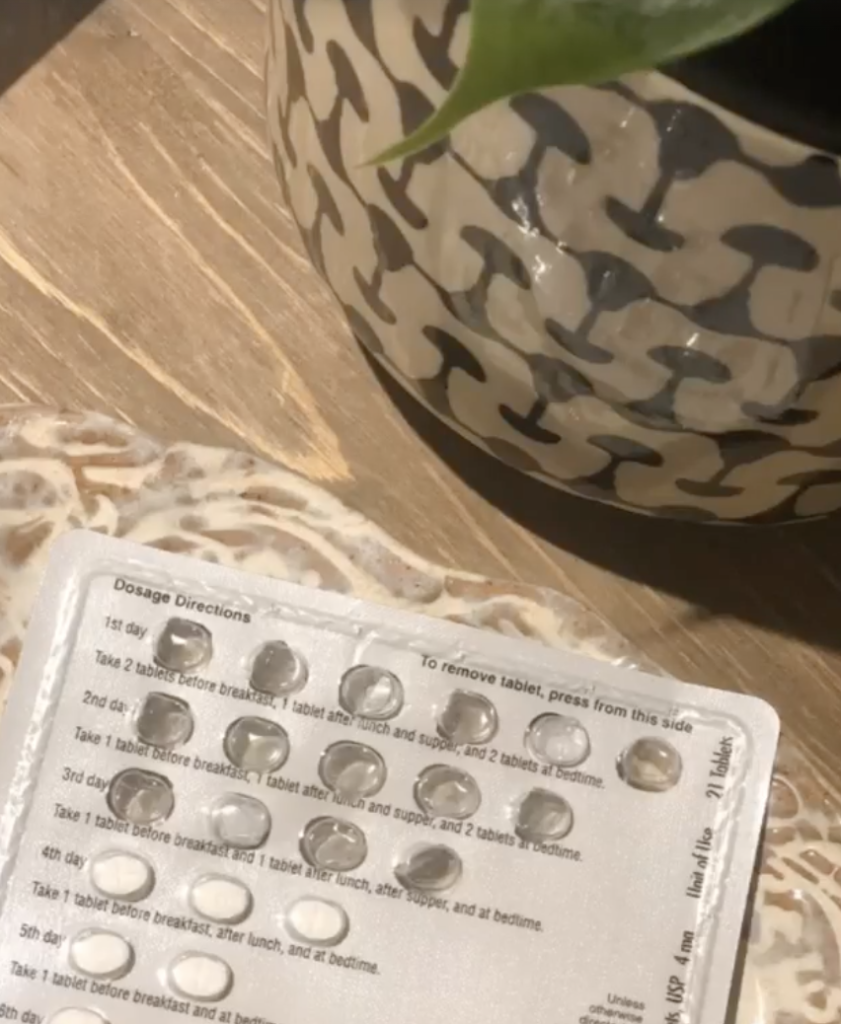

Targeted therapy

I’m on targeted therapy called Alectinib. I’m very fortunate to have that accessible to me and have insurance that does cover a large portion of the cost because it is very expensive, but I’ve responded very well to it.

I have [had] stable scans since the spring of 2020, so very relieved to get that news and, hopefully, continue to get that news every quarter. It’s allowed me to be a dad. It’s allowed me to have manageable side effects, fortunately for me. I know it reacts differently for everybody.

How does Medicare cover cancer? »

There were times early on that were very difficult. It’s a fine balance — what the medicine was doing to my body and how to react — to find that comfort zone of taking it and what am I eating that’s affecting my body. It was tough, but we’re in a much better spot now.

Eating healthy during cancer treatment »

Side effects from Alectinib

The biggest one that I’m challenged with now is being out in the sun. [I’m] very susceptible to burn and being outside as frequently as I am — I don’t like to be indoors at all. I could never live in a big city because I would never see grass. I’ve always got to be outside, so that’s very difficult.

High UV rays, going to the beach — I’m always wearing long sleeves, I’m always wearing a hat, and trying to cover up. Even in early spring, 10 minutes out in the sun on a high UV ray day, I’m getting what feels like chemical burns on my hands, on my face, on my head, and it’s difficult.

Bilirubin levels, liver functionality. There [are] a number of different known side effects that come with the therapy that I’m on so it’s all things that I’ve navigated earlier on than now but continuously monitoring that through blood tests every month.

Everybody needs advocacy. Everybody needs a platform.

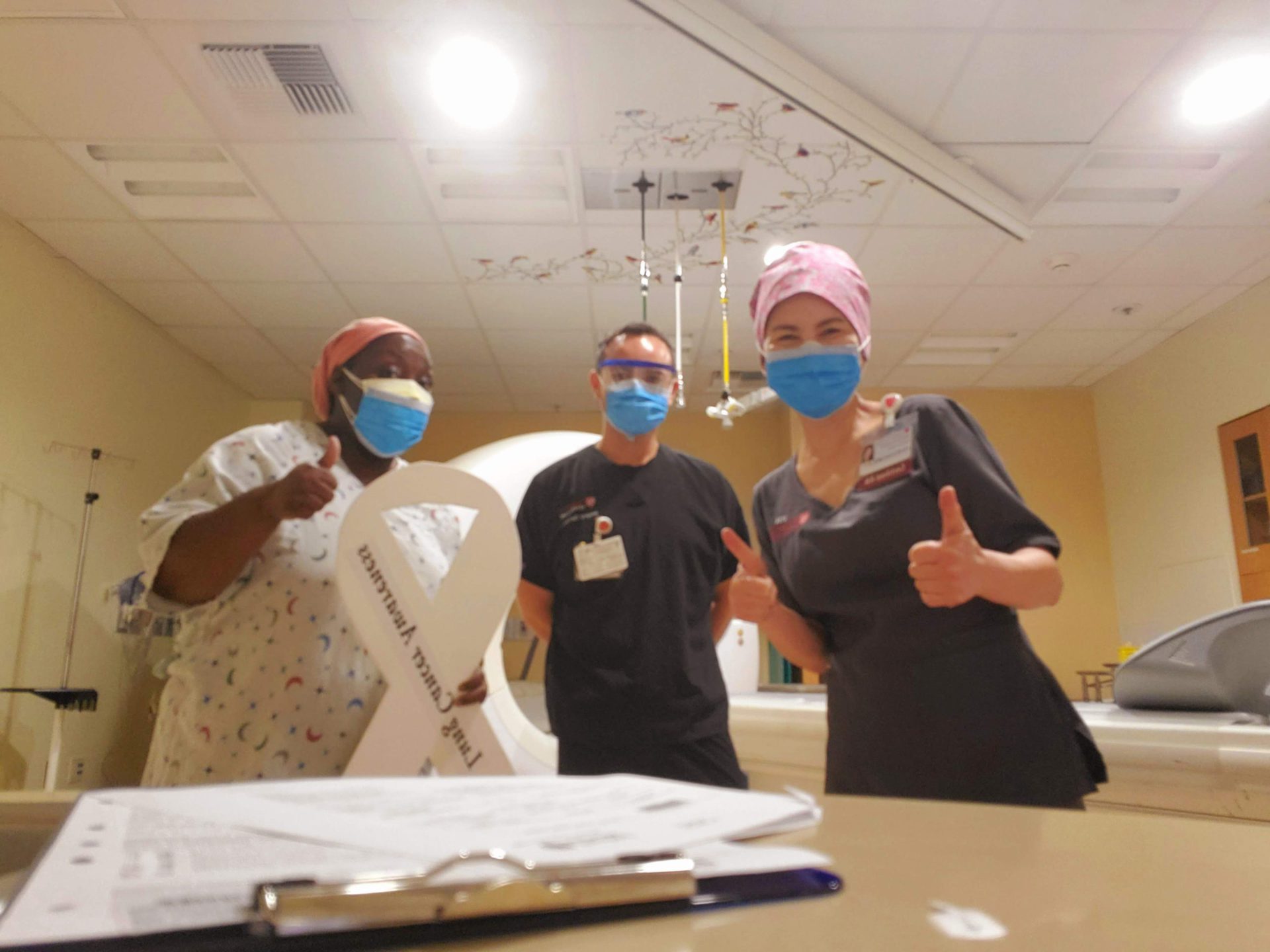

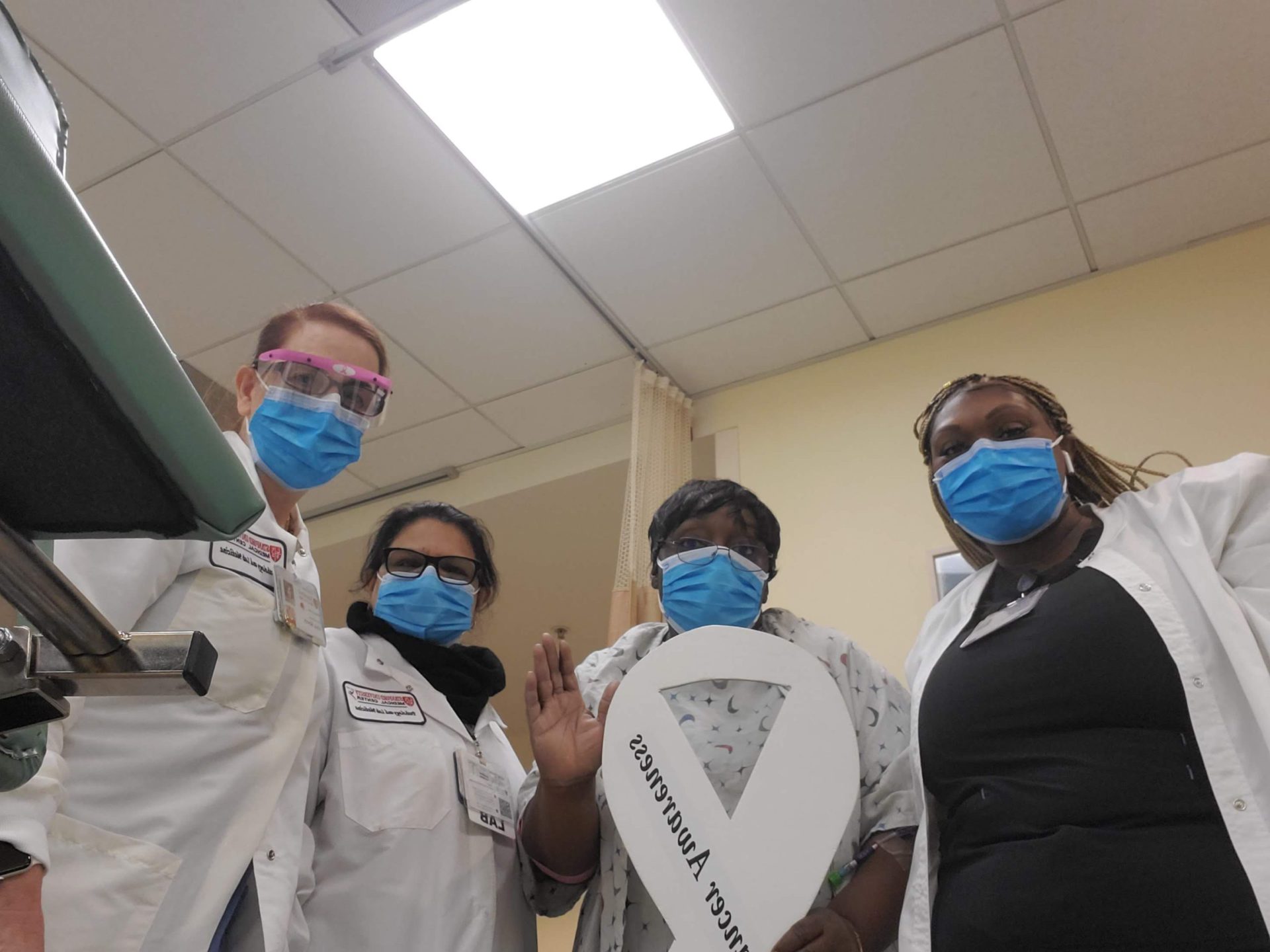

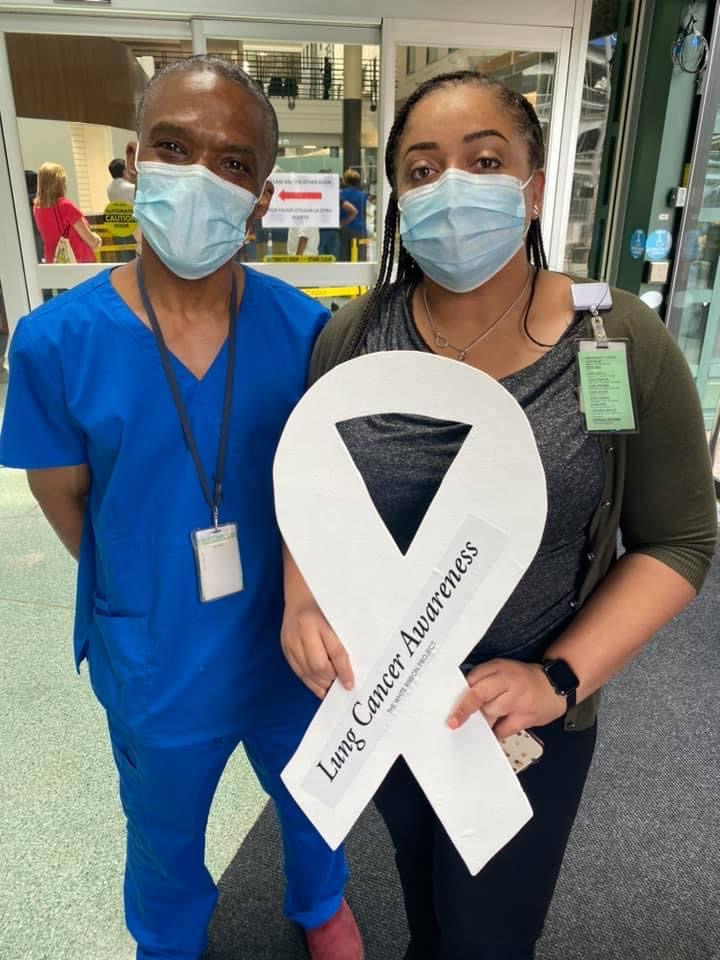

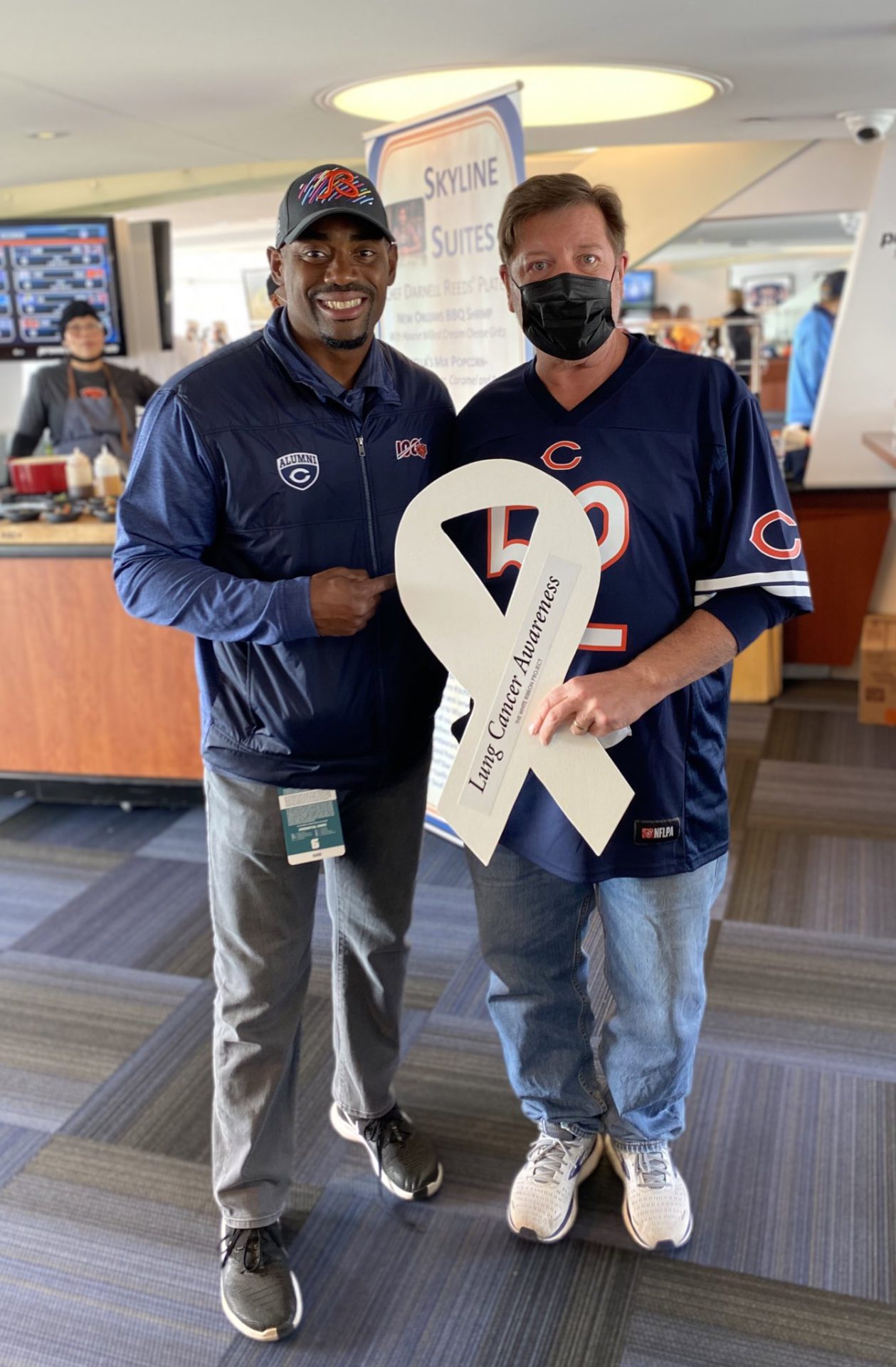

The White Ribbon Project

We’re very active on social media. My wife had seen something and had reached out to Heidi to get a ribbon to display. I didn’t really know much about it, but I’ve had numerous conversations with Heidi.

Heidi’s visions are amazing. It’s not to say that it can’t mean something different to someone else that’s involved. When someone goes and displays a ribbon, if it’s on their front door, [it] could be in support [of] someone else in their family or a friend. It may not be them. How they’re advocating or showing that they’re supporting someone or the community can be different.

When we received our ribbons, we received three and I delivered two to both healthcare systems that I was receiving care at in Philadelphia and then we kept one for [ourselves].

Find out more about The White Ribbon Project »

What does it mean to you and your family to have that?

To me, my thoughts are all-inclusive. Everybody needs advocacy. Everybody needs a platform to push whatever cancer they would like to push from an awareness standpoint. It just so happens that I have lung cancer so when I talk about cancer, it’s probably going to be about lung [cancer] and my experiences and experiences of the individuals that we’ve come across since our journey began.

It’s so important to tell your story and what that means for us is not just for us; it’s for everybody.

It’s so important to cherish that time and experiences that you do have together.

Sharing your cancer story from a father’s perspective

It’s been powerful. It definitely puts things into perspective when it comes to life. What to be upset about, what not to be upset about. It’s okay to get upset still about little things but at the end of the day, it’s so important to cherish that time and experiences that you do have together.

I found sharing my experiences or my story has paid off for other individuals to put things into perspective for them, whether they’re going through something or not. You can always take something from an interaction with someone else and apply that to your own life.

I feel as though we’ve gotten feedback as to how we have navigated this and how we continue to tell our story and help other people [and] how powerful that is to other individuals.

Being able to go out and advocate, that’s what I want my girls to see and learn from because I think that’s really important and that will help shape them in life.

Living with cancer as a parent with young children

Very early on, we received some guidance, to be honest with them. At that point, they were four and two so pretty extreme for them to hear that daddy has cancer. They don’t know what that means so to them, that’s their new norm – Dad going to appointments and whatnot.

We’ve been honest, open, and talk to them. We’ve also shared experiences where there’s the dark side of cancer, but there [are] so many good things that come from sharing your story and putting yourself out there where other people rally around you within what we call our village. Feeling the love from that is pretty special.

Being able to go out and advocate, that’s what I want my girls to see and learn from because I think that’s really important and that will help shape them in life.

I thought [my] quality of life was going to be very poor and I thought the outlook was very poor. But the further we get through this journey, the outlook continues to get pushed out. The further we get, the further that outlook is going to exist.

Is this where I thought I would be? No. I thought [the] treatment was going to be different. But continuing to advocate for us, myself, [and] my family has always been my number one goal. Keeping things as normal as possible for my kids [and] being able to grow from these experiences was very important to us early on.

Learn from other patients about how to talk to kids about cancer »

Being involved in the children’s lives

A lot of bad things come through the pandemic but one of the good things is I get to spend more time with my kids.

Being able to drop Georgia off at school every morning, taking Frankie with me, coming home, putting Frankie on the bus, and then going and picking Georgia up at the end of the day — I can’t describe how important that is for me just to have that interaction and talk to her. When I pick up Georgia, I just talk to her about her day and see what made her happy and what made her upset that day, whatever it was. Just [having] that positive interaction with her is pretty special.

I coach both their soccer teams. And I think, selfishly, with my knowledge and experience with soccer, being able to coach and share that interaction with them is pretty special for me as well.

Being a dad is something that’s very special for me so I don’t think I took it for granted. I think it just has more meaning now being able to do those things.

Inspired by Dan's story?

Share your story, too!

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Stories

Yovana P., Non-Small Cell, Invasive Mucinous Adenocarcinoma (IMA), Stage 1B

Cancer details: Had no genetic mutations; IMAs comprise between 2-10% of all lung tumors

1st Symptoms: No apparent symptoms

Treatment: Lobectomy of the left lung

Dave B., Non-Small Cell, Neuroendocrine Tumor, Stage 1B

Cancer details: Neuroendocrine tumor

1st Symptoms: 2 bouts of severe pneumonia despite full health

Treatment: Lobectomy (surgery to remove lobe of lung)

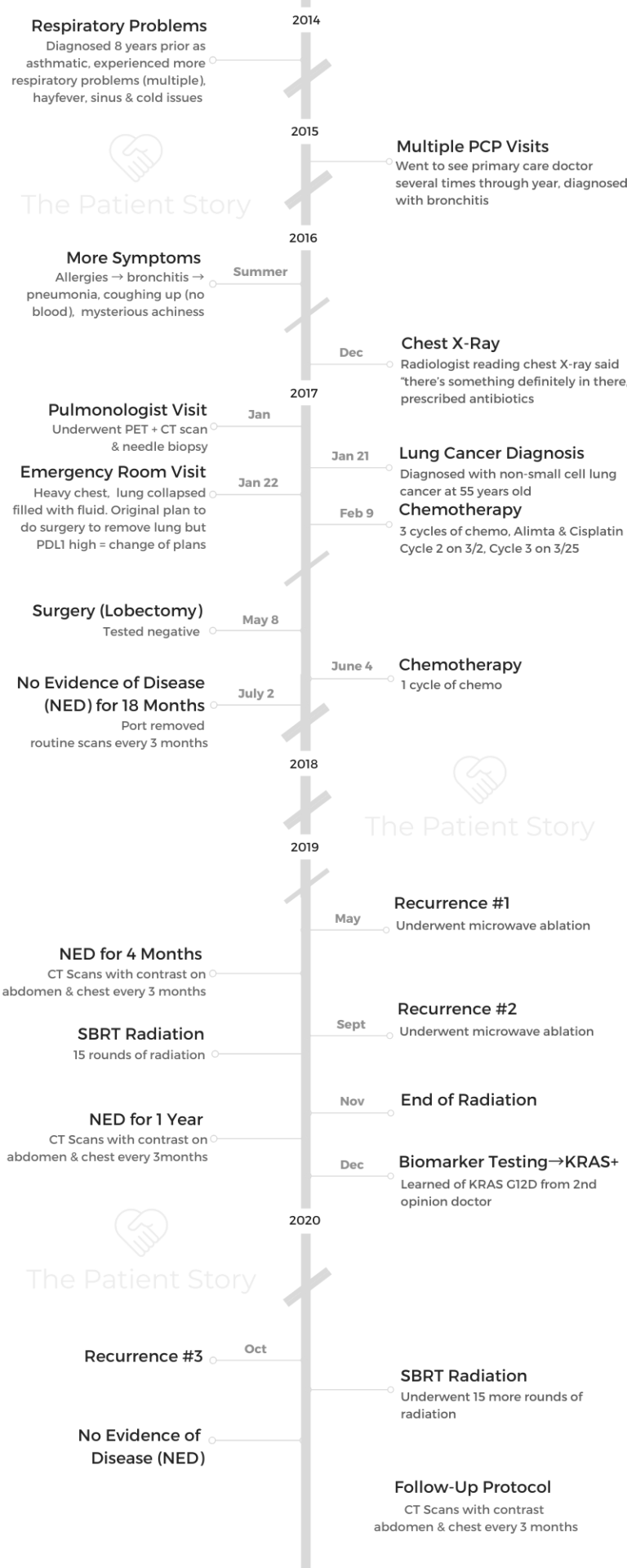

Terri C., Non-Small Cell, KRAS+, Stage 3A

Cancer details: KRAS-positive, 3 recurrences → NED

1st Symptoms: Respiratory problems

Treatment: Chemo (Cisplatin & Alimta), surgery (lobectomy), chemo, microwave ablation, 15 rounds of SBRT radiation (twice)

Heidi N., Non-Small Cell, Stage 3A

Cancer details: Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

1st Symptoms: None, unrelated chest CT scan revealed lung mass & enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes

Treatment: Chemoradiation

Tara S., Non-Small Cell, ALK+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Cancer details: ALK+ occurs in 1 out of 25 non-small cell lung cancer patients

1st Symptoms: Numbness in face, left arm and leg

Treatment: Targeted radiation, targeted therapy (Alectinib)

Lisa G., Non-Small Cell, ROS1+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Cancer Details: ROS1+ tends to be aggressive. It can spread to the brain and to the bones.

1st Symptoms: Persistent cough (months), coughing a little blood, high fever, night sweats

Treatment: Chemo (4 cycles), maintenance chemo (4 cycles)

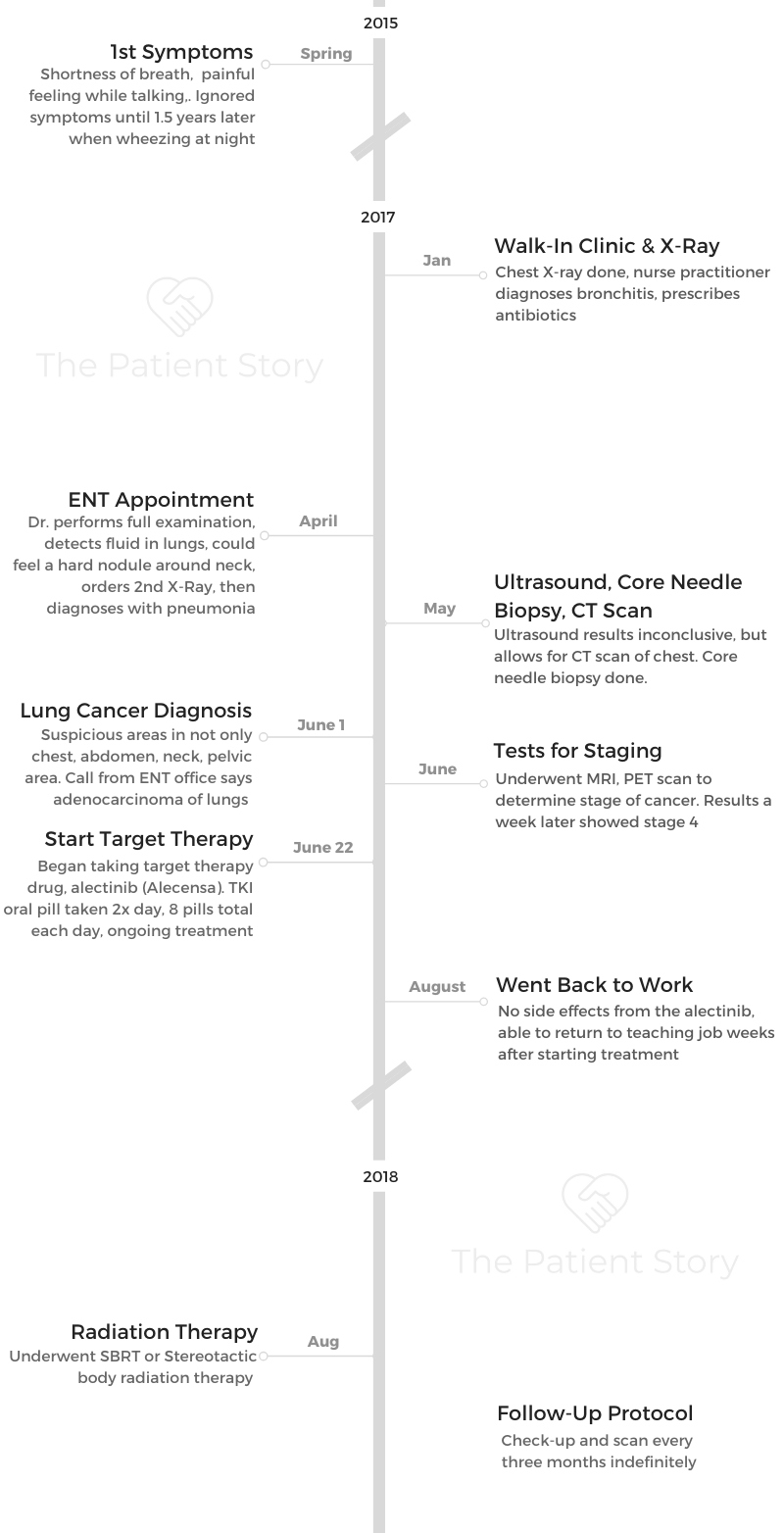

Stephen H., Non-Small Cell, ALK+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Cancer details: ALK+ occurs in 1 out of 25 non-small cell lung cancer patients

1st Symptoms: Shortness of breath, jabbing pain while talking, wheezing at night

Treatment: Targeted therapy (alectinib), stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT)

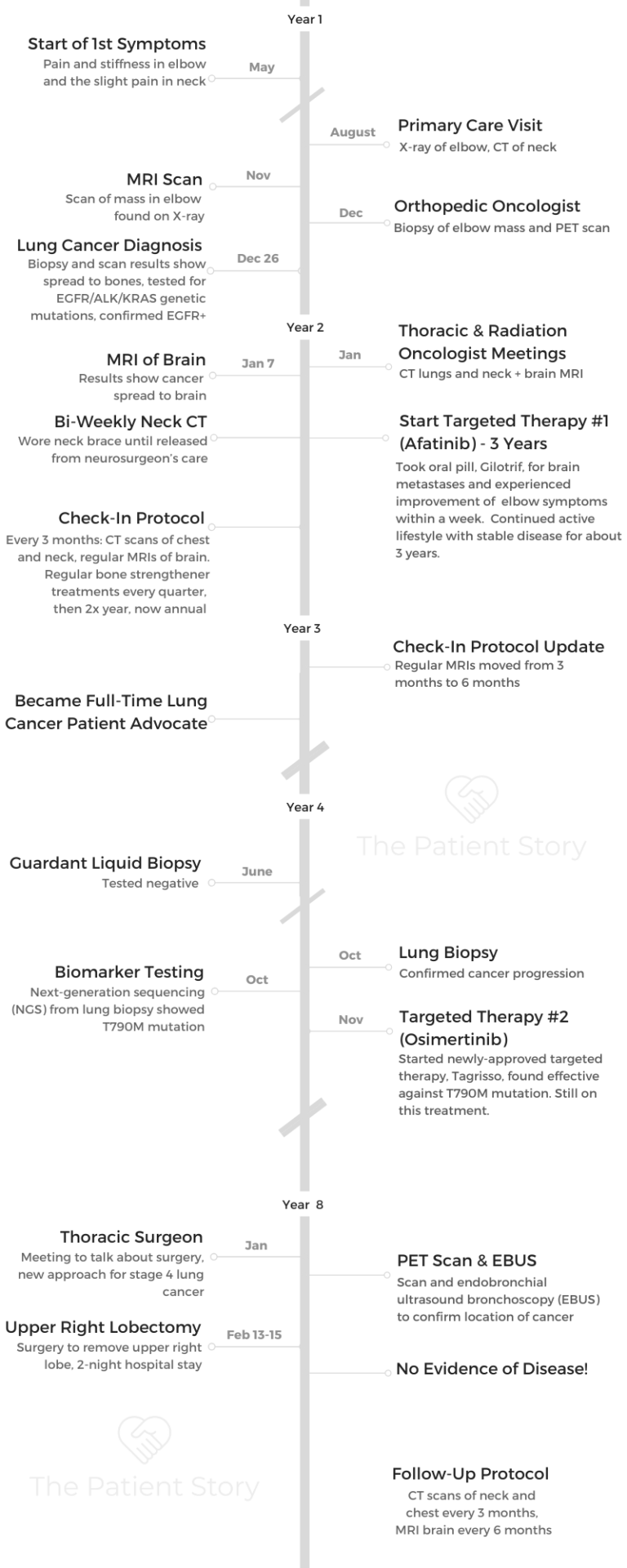

Ivy E., Non-Small Cell, EGFR+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Cancer details: EFGR-positive

1st Symptoms: Pain & stiffness in neck, pain in elbow

Treatment: Two targeted therapies (afatinib & osimertinib), lobectomy (surgery to remove lobe of lung)

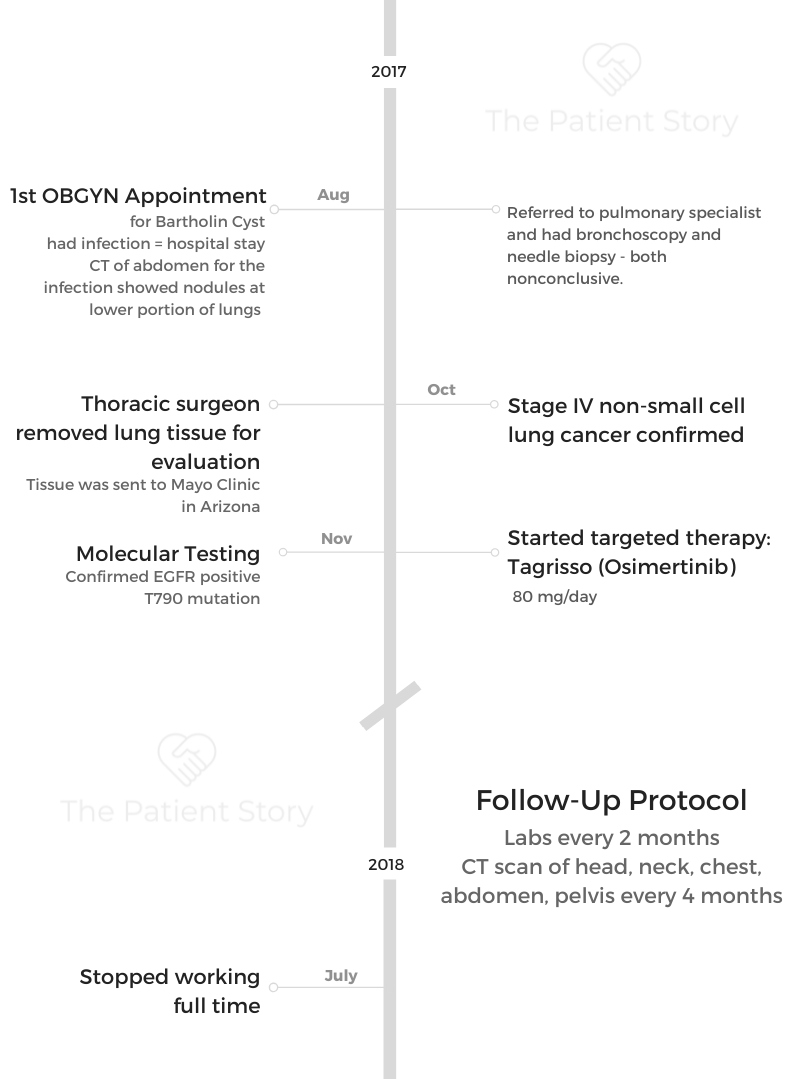

Ashley R., Non-Small Cell, EGFR+ T790M, Stage 4

Diagnosis: Stage IV Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

1st Symptoms: Tiny nodules in lungs

Treatment: Tagrisso (Osimertinib)

Shyreece P., Non-Small Cell, ALK+, Stage 4

Cancer details: ALK+ occurs in 1 out of 25 non-small cell lung cancer patients

1st Symptoms: Heaviness in arms, wheezing, fatigue

Treatment: IV chemo (carboplatin/pemetrexed/bevacizumab), targeted therapy (crizotinib, alectinib)

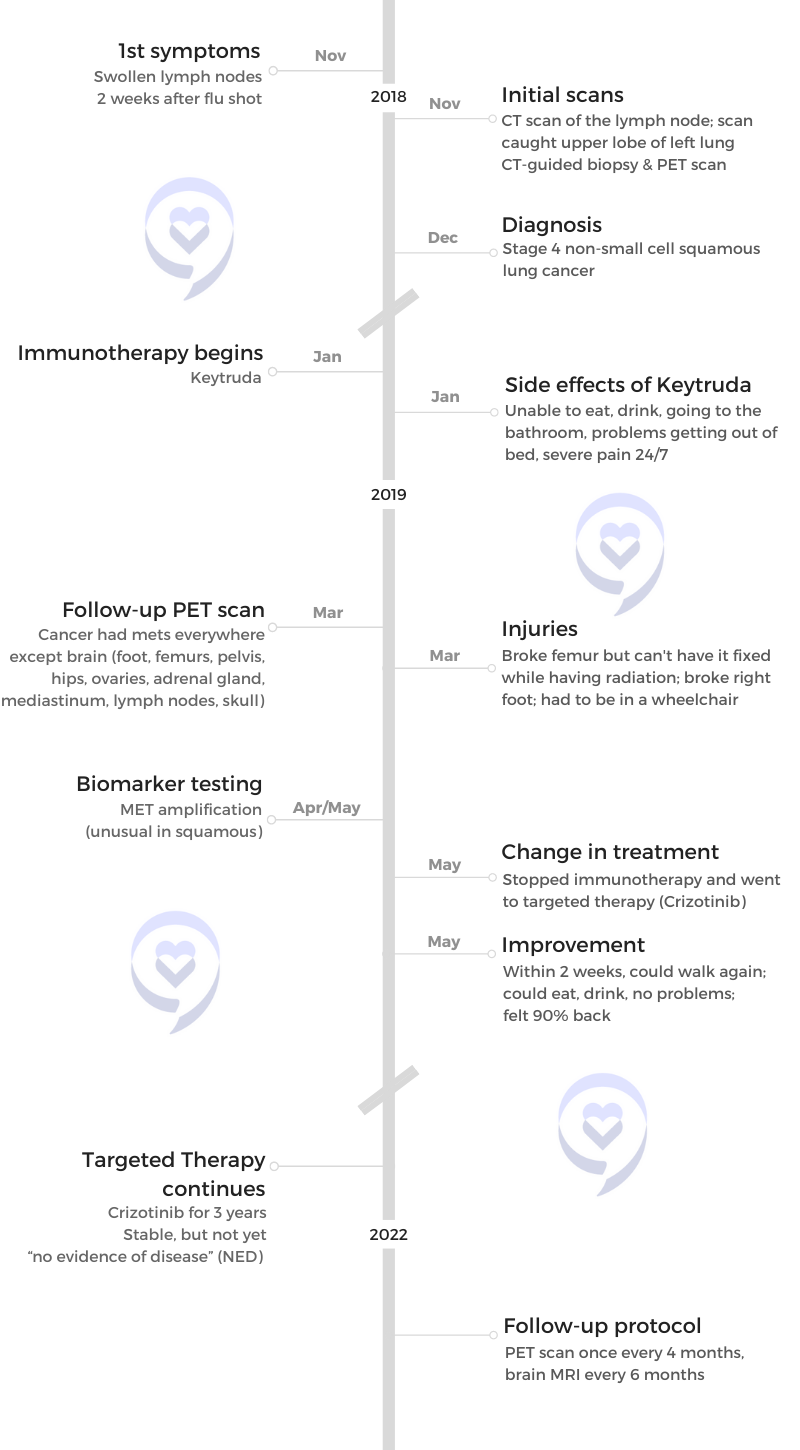

Amy G., Non-Small Cell Squamous, MET, Stage 4

1st symptoms: Lump in neck, fatigued

Treatment: Pembrolizumab (Keytruda), SBRT, cryoablation, Crizotinib (Xalkori)

Dan W., Non-Small Cell, ALK+, Stage 4

1st Symptoms: Cold-like symptoms, shortness of breath, chest pains

Treatment: Radiation, targeted therapy (Alectinib)

Tiffany J., Non-Small Cell Adenocarcinoma

1st Symptoms: Pain in right side, breathlessness

Treatment: Clinical trial of Tagrisso and Cyramza

The White Ribbon Project

Lauren C.

Symptoms: Chronic wheezing, difficulty breathing, recurrent pneumonia and bronchitis

Treatment: Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS)

Dr. Michael Gieske

Background: Doctor fighting for early lung cancer screening story Focus: Encouraging more screening for lung cancer

Heidi Nafman Onda

Background: Diagnosed with stage 3 lung cancer, started The White Ribbon Project to push awareness of anyone with lungs can get lung cancer

Focus: Encouraging lung cancer story sharing, inclusion of everyone in the community

Dave Bjork

Background: Underwent stage 1 lung cancer surgery, in remission for decades, hosts own cancer researcher podcast

Focus: Encouraging lung cancer story sharing, passionate advocate for early screening and biomarker testing

Anne LaPorte

Background: Spent 35 years as nurse, then caregiver to father & daughter both diagnosed with cancer, before diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer, herself (EGFR+)

Focus: Encouraging patient and caregiver advocacy, biomarker testing for more treatment options, early detection

Bonnie Ulrich

Background: Focused on family and being the "fun grandma," 3x lung cancer survivor with a smoking history

Focus: Building empathy for all patients, regardless of smoking history, and encouraging early detection for everyone to save lives

Rhonda & Jeff Meckstroth

Background: Jeff was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer and given months to live, but his wife, Rhonda, fought for a specialist that led to biomarker testing and better treatment options

Focus: Education of biomarker testing for driver mutations, patient and caregiver self-advocacy

Pierre Onda

Background: Primary care physician whose wife, Heidi, diagnosed with stage 3A lung cancer. Built first white ribbon for The White Ribbon Project.

Focus: Building empathy for all patients, regardless of smoking history.

Chris Draft

Background: Chris' wife Keasha passed away from stage 4 lung cancer one month after they married. He's been a passionate lung cancer advocate ever since.

Focus: Leading with love, making connections to grow lung cancer community, NFL liaison