Why are My Prescriptions So Expensive?

Cost Plus Drugs Founder & Mayo Clinic Doctor Explain

Prescription drug prices in the United States are significantly higher than in other nations. In fact, 1,200 prescription drug prices rose faster than the rate of inflation between 2021 and 2022.

In this conversation, Alex Oshmyansky, founder and CEO of the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company, and Dr. Vincent Rajkumar, a hematologist oncologist at the Mayo Clinic, talk about the exorbitant costs of medicines, the impact it has on patients and families, and why the current system needs to change.

The interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

The more you delve into it, you find it’s not simple and that’s why no one is able to fix it… You just don’t even know where to start if you want to pick something.

Dr. Vincent Rajkumar

Introduction

Dr. Vincent Rajkumar, Mayo Clinic: I work at the Mayo Clinic. I’m a hematologist oncologist and my disease specialty is multiple myeloma. I do research, education, and practice as far as myeloma is concerned.

I also have an interest in drug pricing, which started because I run a lot of clinical trials and work with new drugs. I do studies on racial disparities so I’m aware of the impact [of] cost of medicines and health care [on] various communities.

I also edit the Blood Cancer Journal along with my colleague, Dr. Tefferi.

When it comes to drug prices, there’s [an] impact on the patients, who are the people actually affected by the disease, as well as the cost of taking care of the disease. [I] hear not only from patients that I myself treat but also from patients across the country.

I wrote my first paper on [the] cost of prescription drugs in 2012 and it was focused on cancer — the high price of cancer drugs and what we can do about it. It was mainly because I worked on Thalidomide, which was the drug that was banned in the 1950s because it caused teratogenicity.

I’m probably the only physician in the world who actually used Thalidomide to treat leprosy, which was approved for, and subsequently started using it for myeloma. I was in India using Thalidomide for leprosy and it was given to us basically free of cost in huge buckets that you could use to treat patients.

Then I come to the US and I find Thalidomide costs $10,000 a month. This drug should cost $10!

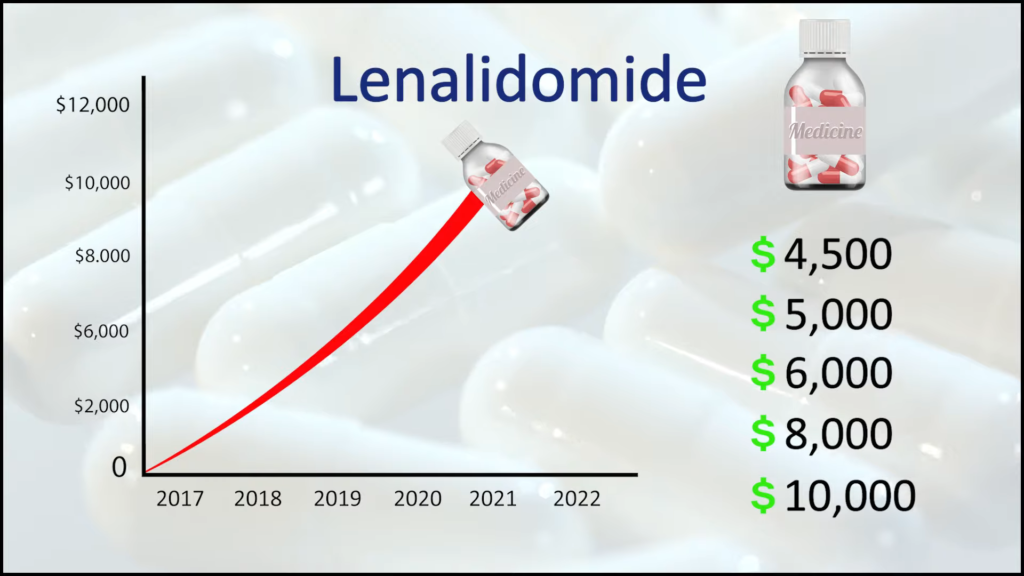

I see the price of Lenalidomide launched at around $4,500 and then going up every year to $5,000, $6,000, $8,000, $10,000… and you’re going, What’s happening? That’s when I said I really need to understand the root cause of these problems.

The more you delve into it, you find it’s not simple and that’s why no one is able to fix it. It starts with monopolistic pricing then the middlemen and the whole infrastructure that you just don’t even know where to start if you want to pick something.

Alex Oshmyanksy, Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company: I’m a board-certified diagnostic radiologist. I have a PhD in applied mathematics. When I was a kid, I was going to be a string theorist, so a high-energy particle physicist. I was being fast-tracked into that. With all the wisdom of a teenager, I decided that wasn’t going to be impactful enough in the real world so [I] made a hard shift [in] my last year of college and decided to major in biochemistry instead. [I] graduated at 18 and went on to medical school and completed an MD-PhD program.

While I was at Hopkins, I was working with a pulmonologist on a research project. One day, he came in infuriated because two of his patients died over the same weekend. They both needed a drug called Bosentan, which treats primary pulmonary artery hypertension — hypertension specifically of the big blood vessel that comes out of the heart and goes to the lungs — and they both needed it urgently.

At the time, the medication cost $10,000 for a month’s supply, despite the fact that it was long off-patent [and] was a generic product at that point. They were meant to apply to a patient assistance program set up as a nonprofit by the manufacturer who made the product, got caught in the red tape, and both of them tragically died [on] the same weekend.

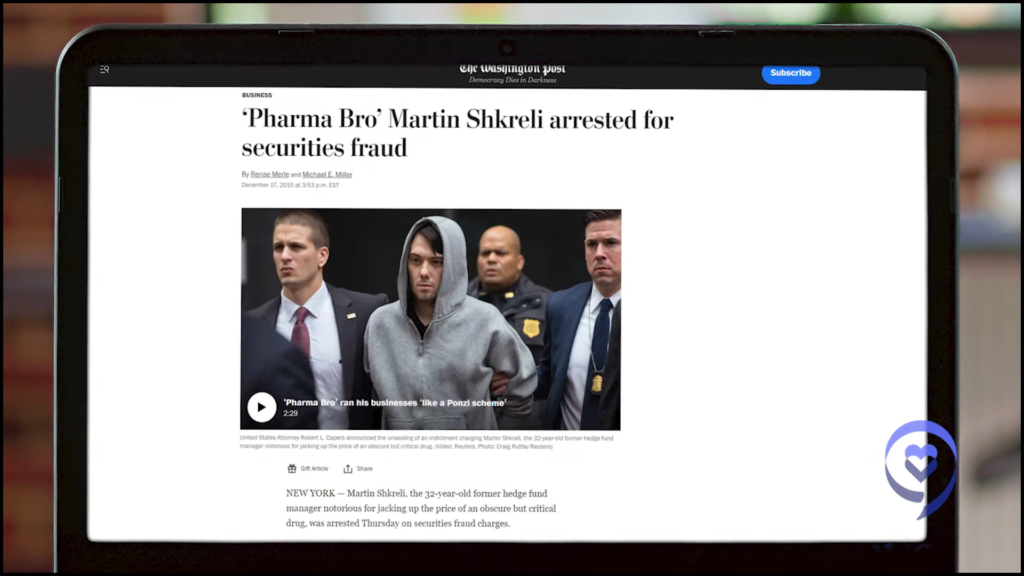

I had been angry about these topics for some time and you think that’d be enough to set me off. But what really became the straw that broke the camel’s back was Martin Shkreli, the so-called pharma bro.

In 2015, he was a social media villain-of-the-day type [of] guy. He was a hedge fund manager who took over a pharmaceutical company and increased the price of a drug called Daraprim — generic Pyrimethamine, primarily used by indigent patients or immunocompromised — by over 10,000%, hundreds of dollars a tablet.

I got very mad and some of my friends, who are also doctors, [also] did. We decided very naively, “Let’s set up a nonprofit pharmaceutical company that will make drugs [and] sell them at cost.” While working as a doctor, [I] went out for the better part of three to four years trying to raise funding for the nonprofit and did not succeed. Failed spectacularly — raised $0 beyond what I put in myself.

Eventually, [I] got talked into converting it to a for-profit public benefit corporation — [a] for-profit company but with a registered public mission with the state. [I] sent Mark Cuban a cold email on a whim and surprise, surprise! He reads all his emails. And the rest, as they say, is history.

The path is incredibly complicated. It’s very convoluted and that’s by design.

Alex Oshmyansky

The path from pharma to pharmacy

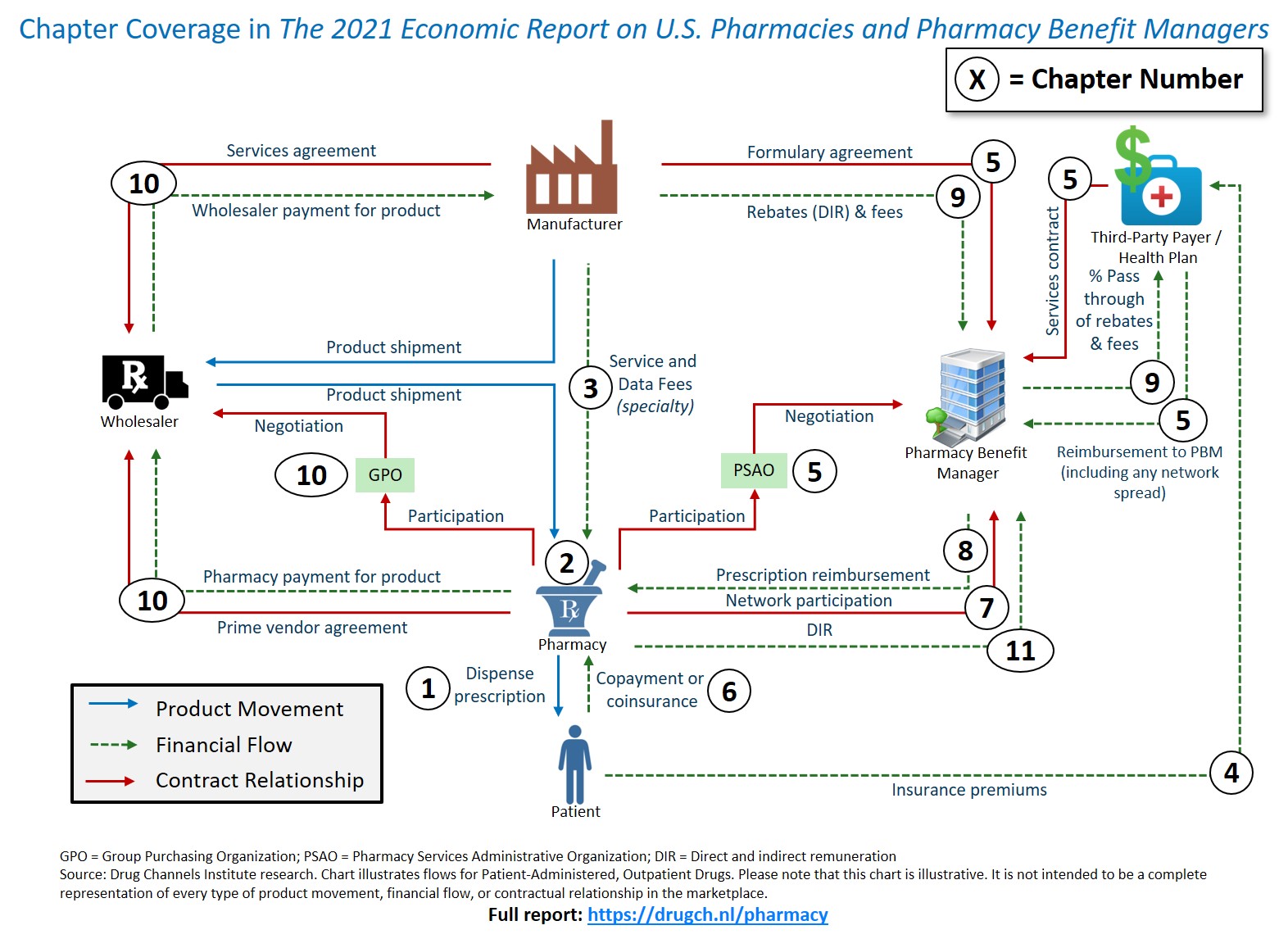

Stephanie, The Patient Story: There is this path that goes from the pharmaceutical companies — with the research and development of these drugs — to the pharmacies where you and I go to pick up the drugs and the prescriptions. Could you summarize what happens? What is in this path here?

Alex, Cost Plus Drugs: The path is incredibly complicated. It’s very convoluted and that’s by design. There’s a layer of financial engineering that takes place between you and actually purchasing the product.

Pharmacy benefit managers are firms [that] are outsourced to by insurance companies to decide which products are covered by insurance. They manage all the payments. Back in the 1980s, before computers were as widespread, they were initially there to literally process payments. They would get paid to do the paperwork when a prescription insurance claim was submitted.

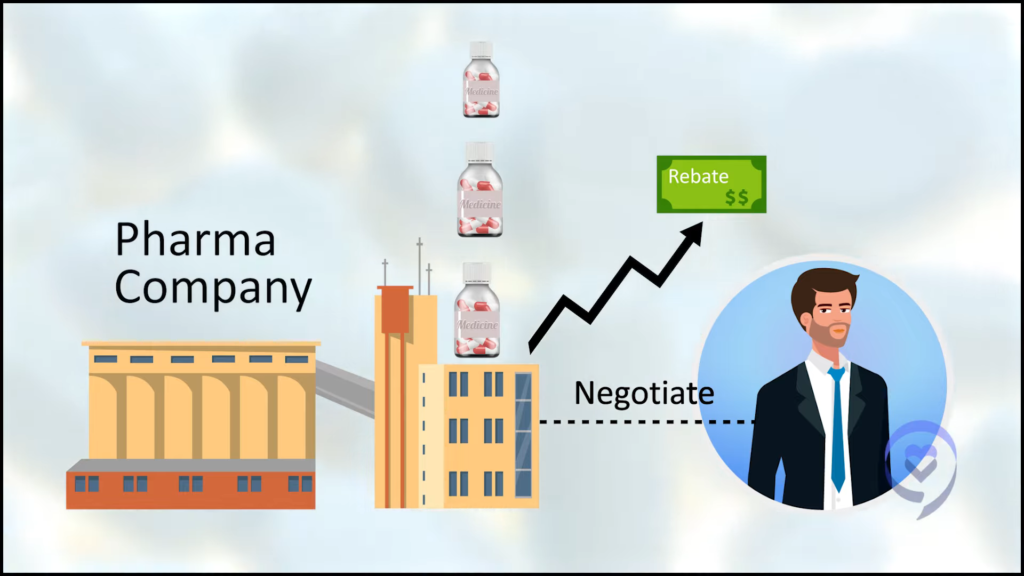

What they realized over time was, Since we’re paying for the drugs anyway, we can collectively bargain for the drugs. They turned into negotiators for drug prices, which sounds good.

Eventually, what they realized was, The way we’re getting paid is we take a percentage of the savings. The best way to make the most money was for the drugs to be as high a price as possible to start out with before they started negotiating down.

Imagine you wanted to buy a [car] but you hate negotiating at the car lot. It’s miserable. Everybody hates that. Somebody comes up to you and [says], “Hey, I will do the negotiating for you and in exchange, I get 10% or 20%,” or whatever the amount of money they save you. You’re like, “You know what? That’s worth it to me. I hate negotiating.”

The negotiator comes back and says, “Hey, amazing news. I got you a great deal. I got you 90% off of your [car].” “That’s amazing. How did you do that?” “I’m really, really good at negotiating.” Come to find out the sticker price on the [car] was $1,000,000 and you’re paying $100,000 for your [car] plus the fee from the negotiator, which is another $90,000. All of a sudden, you’re paying $200,000 for your [car]. That sounds like a crazy, over-the-top example, but it really happens.

What they (pharmacy benefit managers) realized was… the best way to make the most money was for the drugs to be as high a price as possible to start out with before they started negotiating down.

Alex Oshmyansky

The example drug that I use all the time — because it’s the most extreme edge case — is a product we offer called Imatinib, which is a chemotherapy product. It’s a tyrosine kinase inhibitor for chronic myelogenous leukemia and you need to be on it for many, many years. The list price, the so-called average wholesale price, is $10,000 for a month’s supply.

Now, if you get it through your insurance and you have a high deductible plan, it’ll be “adjudicated” at between $2,000 and $3,200 as the negotiated discount price plus the margin for the PBM. Meanwhile, if you get it from the Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company, it’s $39 for a month’s supply. That delta between $3,200 and $39 is being taken by somebody and it’s actually not the pharmaceutical manufacturer. It’s the intermediaries in the pharmaceutical supply chain taking a percentage of the rebate. It’s just one of the many, many scams [that] has evolved over the past 30 years to take advantage of the sick and vulnerable and it’s absolutely morally repugnant.

That delta between $3,200 and $39 is being taken by somebody and it’s actually not the pharmaceutical manufacturer.

Alex Oshmyansky

Drug price disparity

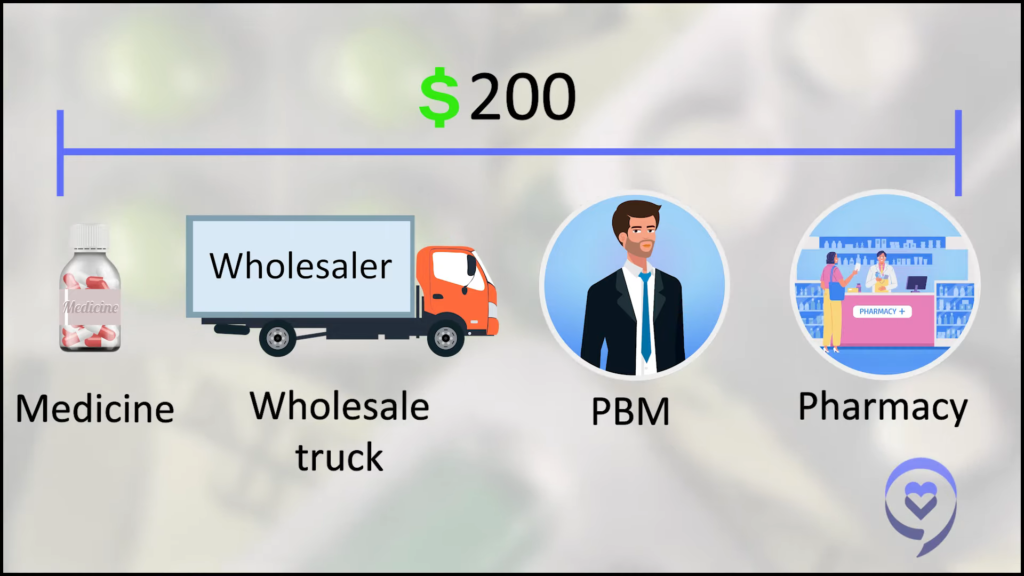

Dr. Rajkumar, Mayo Clinic: You don’t see that kind of spread anywhere else with any other product. It’s happening because there are many people marking the price up so that what is $400 when it leaves pharma could be marked up to $4,000 by the time it reaches the patient.

Unless the patients are aware, you could be vulnerable to high prices, whether it’s insulin, Gleevec, a new cancer medicine, [or] an old medicine. What we find is where the prescription goes, how the prescription is written, [and] what you’re aware of as far as the coupons and rebates you get can really affect how much you pay for that medicine. And it’s not a small dollar amount.

There are many people marking the price up so that what is $400 when it leaves pharma could be marked up to $4,000 by the time it reaches the patient.

Dr. Vincent Rajkumar

Stephanie, The Patient Story: We know about pharma companies and the R&D that happens there. There’s a price set. Can you describe the path?

Alex, Cost Plus Drugs: Basically, the wholesalers do take a markup. On specific products, it can be a very, very high markup. Our initial product, Albendazole, an antiparasitic drug, is available from us for [about] $30 for two pills and a complete course of treatment tends to be two pills. But, as far as we could tell, about $70 a pill from the pharmaceutical wholesalers if you purchase it directly from them.

There is a lot of inflation that happens at the wholesaler level. As a general rule of thumb, the price of a drug approximately doubles once you purchase from a wholesaler. That sounds like a lot and it is. It’s perhaps a bit too much but at least they serve a function. They send the products around the country.

The best way I can describe it is it’s basically a pile of spaghetti with lines going [in] every direction from all the various different actors — PSAOs (Pharmacy Services Administrative Organizations), GPOs (Group Purchasing Organizations), the insurance companies, the pharmacy benefit managers, patients — about the way money winds up flowing in the pharmaceutical industry.

The way I think about it is this is a feature, not a bug. The system is so artificially complicated that it permits basically theft in the service of it.

There is a lot of inflation that happens at the wholesaler level. As a general rule of thumb, the price of a drug approximately doubles.

Alex Oshmyansky

Understanding drug pricing

Stephanie, The Patient Story: Let’s just give an example for a $10 pill. Let’s say that’s what the pharmaceutical company has set the price on. Can you give an example of “roughly” what that could look like by the time it gets to us?

Alex, Cost Plus Drugs: On average, it’ll be about $20 from the wholesaler. The pharmacy will probably add on let’s say $10 just to keep the numbers round. It’s usually maybe more $6 to $8, but let’s say at the pharmacy, it’s about $30. Then the price manipulation starts to happen and that’ll be the actual price at the end of the day.

There’ll be a number of artificial prices put on it depending on if it’s a brand name drug [or] a generic drug. Let’s say it’s a generic drug for the sake of argument. Generally, a generic drug is priced at a pharmacy benefit manager at about an 85% discount. They will say that the price of the drug is, in this case, $200 so that’ll be the price you see if you try to pay cash at a pharmacy without using a special program of some kind. It’ll be artificially inflated to $200 so they can negotiate it back down to $30 and then charge a little bit more for the service of negotiating.

The manufacturer will have to pay a rebate to the PBM, who in turn takes a cut and forwards part of the rebate to the insurance company that’s paying the ultimate bill. But the insurance company has to pay the whole thing first. [Plus] the wholesaler, somewhere in the mix of all of this, holds the money for six months and makes money off of the interest. It’s a whole morass.

Dr. Rajkumar, Mayo Clinic: Unfortunately, there’s no rhyme or reason for these prices. Patients can go and play around on some websites, like GoodRx.com. [If] you enter the name of a drug and order a 30-day supply, you would find a coupon for [a] 90% discount. If you order [a] 60-day supply or a 90-day supply, you may get a [bigger] discount.

For example, Lenalidomide, which is Revlimid. Medicare spends more money on Lenalidomide than just about every other drug. The drug costs the same whether it’s a 5 mg tablet, 10 mg tablet, 15 mg, or 25. [If] you take two 5 mg tablets, [you’ll] be paying double the amount — $36,000 instead of $18,000. I’m giving an extreme example but [for] many drugs, you have to really look. Taking the drug twice a day just because you want to break it down is not going to be the same price. You pay double.

Stephanie, The Patient Story: How can there be such a disparity going from point A, which is the same, but in a hundred different locations? It’s just all over the map.

Dr. Rajkumar, Mayo Clinic: Yeah, and it’s hard to regulate. There is no transparency. If you try to say let’s not have rebates, then the people in the middle could just convert rebates into fees. This is how much I charge for me to buy the drug from someone and give it to you. They can add five different types of fees in between so that the price of the drug gets marked up.

I think government and regulators have to take a close look at this. The Federal Trade Commission [has] to really look into who’s making profits, how, what is competitive, what is anti-competitive — all of that has to be looked into.

Meanwhile, patients, as well as physicians, can be aware of the system. Be aware that it’s not just simply getting a prescription and getting it filled at the closest pharmacy. Be aware that your copay for insurance might be higher than if you just paid cash for the same drug without going through your insurance company. And that could be substantial.

After I posted my tweet, people were posting, “It cost me $250 with insurance and $10 cash.” Then why have insurance? Unfortunately, even physicians are not aware of all of the disparities. You must be aware of it. Just check. Make sure your physicians check.

I tell my colleagues [to] make sure you ask patients about affordability. Can you afford this medicine? What is your insurance like? How much copay do you have? Just talking to patients and inquiring [about] their situation so that if somebody says, “No, doc, don’t worry. My prescription drugs are fully covered. I have a $10 fixed copay.” Fine, no problem. But if someone says, “I pay 5% of my prescription cost as a coinsurance,” then you better be careful how much that drug is billed, that you’re sending it to the right pharmacy.

Finding the best price for your prescription

Alex, Cost Plus Drugs: As a general rule, the worst prices will be at your big national chain pharmacies. Obviously, I’m biased but generally, for most products, we tend to have the best price or at least close to it.

We are a registered pharmaceutical wholesaler. We buy the products [directly] from the manufacturers at our flat 15% markup on top of it, a $3 dispense fee, and $5 shipping and handling at CostPlusDrugs.com. You can get any of about 1,000 generic products from our site as of today and we’ll be adding on brand-name products in the near future.

Dr. Rajkumar, Mayo Clinic: Many, many people are finding out that just going to Cost Plus Drugs and getting the generic might be much cheaper than paying the coinsurance and that shouldn’t be that way. It just doesn’t make sense.

Stephanie, The Patient Story: What can people do? What about the people who don’t have their drugs covered yet by Cost Plus? I know you’re working on that. What can they do at home?

Alex, Cost Plus Drugs: There [are] a number of different resources. Always check with the manufacturer’s website. There may be a co-payment assistance card or other cash assistance program. They might not be the most convenient things in the world but, oftentimes, you can get the cash out of pocket. You have to pay down significantly that way.

Discount card programs, like GoodRx or SingleCare, might be an opportunity. They tend to be more generic-focused as opposed to brand-name products. I think those would be the two easiest things if you need a brand-name, on-patent medication.

Generally, the easiest way to know is if it has a really easy name to pronounce, it tends to be a brand-name medicine. Google the name of the medicine, check the manufacturer’s webpage, and see if there’s a program available to help you afford it.

If it’s a generic one, check CostPlusDrugs.com. If we don’t have it, look for a discount card program; maybe there’s a discount available there. You can even ask your pharmacy, “Can I pay cash?” and see. Oftentimes, the discount cards are unnecessary and they’ll just sell you the drug cheaply.

Always check with the manufacturer’s website… Discount card programs might be an opportunity.

Alex Oshmyansky

The road ahead

Stephanie, The Patient Story: That’s amazing advice. Between the brand name and the generic, has it been much harder with one than the other?

Alex, Cost Plus Drugs: The generic companies, it’s been easier to get ahold of those products just because there [are] more of them. There’s more competition and more people looking at ways to get their products across

The brand-name companies [are] not necessarily beholden to the PBMs but it’s a big risk to them to go outside of the PBM structure, which is not great. They’re not thrilled with it because, from their perspective, they do all the R&D, they take all the legal risks, [and] they take all the bad publicity from the public when people complain about high drug costs. They’re like, Why are these companies getting a third of the revenue from our products? It’s insane.

At the same time, the status quo works for them. It’s a bit of a risk going with us but I think in our conversations behind the scenes, they’re willing to take that risk at this point. They’re kind of sick of the status quo as well. We’ll be bringing them on in the near future.

Stephanie, The Patient Story: What is the next big vision of what this landscape will be like for people?

Alex, Cost Plus Drugs: Adding more and more products, brand-name products, on a very tactical level. Beginning to work with insurance companies over the course of the next year — on our terms, of course.

Hoping long-term to change the status quo to something more sustainable based on taking the pharmaceutical marketplace and making it like any other marketplace — where you can see what the prices are and make rational, informed decisions as a patient and as a consumer based on real prices instead of make-believe numbers.

Thankfully, things are changing and they’re changing for the better.

Dr. Vincent Rajkumar

Advice for patients and families

Stephanie, The Patient Story: This was a huge eye-opening conversation. Is there anything else you’d like patients and families to know?

Dr. Rajkumar, Mayo Clinic: I just want patients and families to know, number one, people are taking notice and people are aware. People are becoming aware that this is a problem and have decided we have to change. People like me, Patients for Affordable Drugs, [and] many others are now taking notice that the others in the system are not playing well — pharmacy benefit managers, wholesalers, pharmacies — and we have to advocate for reform in that area.

I am also very happy that people like Mark Cuban have taken it on themselves. When the CEO was talking at Mayo, he said they started with 12 drugs and within a year, they’ve got almost 1,000 drugs at prices that are lower than any pharmacy in the US. Then now, hopefully, they can negotiate with pharmaceutical companies and get insulin and brand-name drugs. We’ll have to wait and see.

I don’t have any inside information, but patients should be aware that, thankfully, things are changing and they’re changing for the better. As long as they are aware that prices can be varied and physicians are aware, then even within the current system, they can find a lot of drugs — including cancer drugs — at affordable pricing.

Hoping long-term to change the status quo to something more sustainable… taking the pharmaceutical marketplace and making it like any other marketplace.

Alex Oshmyansky