Sara’s Stage 3A High-Grade Serous & Clear Cell Carcinoma Ovarian Cancer Story

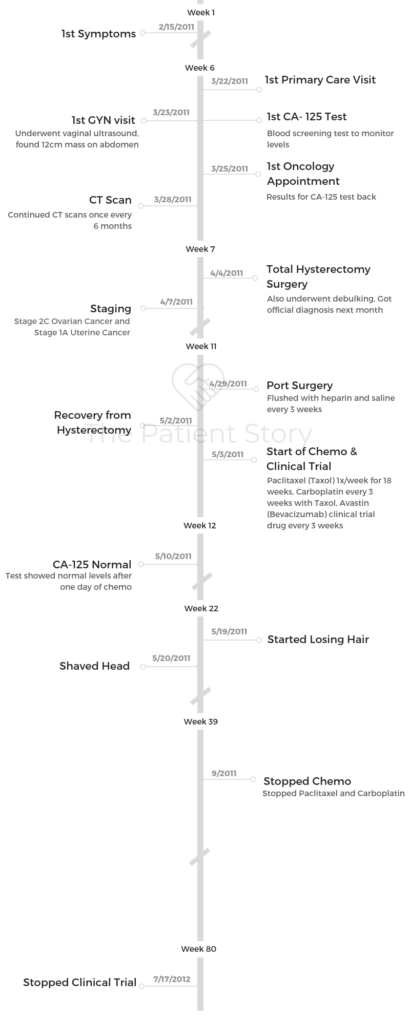

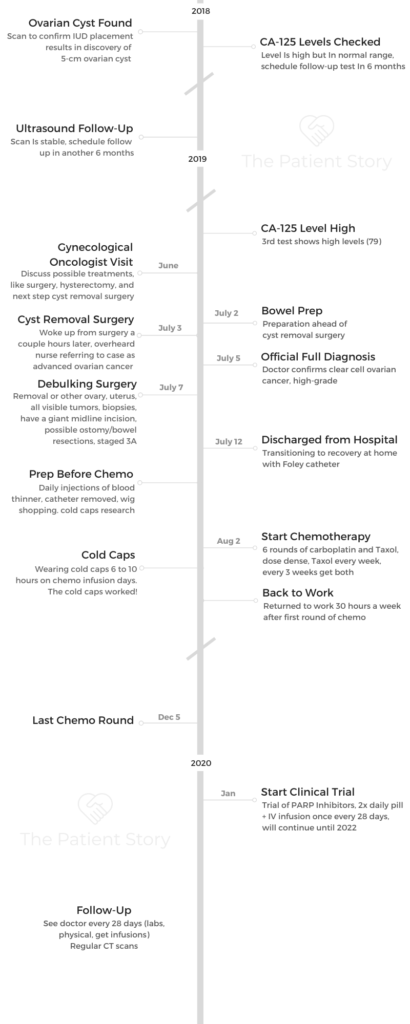

Sara shares her stage 3A clear cell, high-grade serous ovarian cancer story, from getting diagnosed at just 34 years old to going through debulking surgery, chemotherapy, and a clinical trial involving PARP inhibitors.

She also dives deep into how she navigates life with cancer. Sara describes how she’s managed quality-of-life issues, including using cold caps to prevent hair loss, self-advocacy as a patient, finding her cancer community, dealing with scanxiety, processing the loss of fertility, and transitioning to survivorship.

You can read her in-depth story below and watch our conversation on video. Thank you for sharing your story with us, Sara!

- Name: Sara I.

- Diagnosis (DX)

- Ovarian cancer

- High-grade serous

- Clear cell

- Stage 3A

- Age at DX: 34 years old

- 1st Symptoms

- Random sharp pains

- Unrelated scan shows cyst

- Treatment

- Debulking surgery

- Chemotherapy

- Carboplatin

- Taxol

- Clinical trial

- PARP inhibitors

- Twice daily oral pill + IV infusion once every 28 days

- Two-year trial

- Sara's Story on Video

- First Symptoms

- Getting Diagnosed

- Treatment Decisions

- Debulking Surgery & Recovery

- How did you make the decision to pursue a debulking surgery?

- Self-advocating for more anesthesia pre-surgery

- Describe waking up from the surgery

- Transitioning to recovering at home

- Dealing with the mental recovery

- How long did surgery recovery take?

- When could you resume “normal” pre-surgery activity?

- How did you manage the Foley catheter

- Processing the situation at home

- Chemotherapy & Side Effects

- Describe the chemotherapy regimen

- Dealing with having to delay chemo because of neutropenia

- When did the side effects get the worst?

- Describe the Neupogen shots

- List all the chemo side effects

- How did you manage side effects?

- Did side effects get better or worse?

- Describe your work schedule during chemotherapy

- Working and working out were ways to feel “in control”

- Managing Hair Loss

- Clinical Trial

- How did you start a clinical trial the following month?

- Describe the preparation ahead of the clinical trial

- Learning how not to put things off

- Describe the clinical trial

- What drove you to participate in the clinical trial?

- Knowing about the drugs in the clinical trials

- Describe the clinical trial drug side effects

- Managing the side effects

- Why did your doctors say they wanted to pursue the clinical trial?

- The nature of ovarian cancer and recurrences

- Quality of Life

- The importance of self-advocacy

- You advocated to get paperwork for your own records

- The power of being an informed, engaged patient

- The need for more awareness about ovarian cancer

- Finding your cancer community

- The importance of having caregivers

- Guidance on how to support cancer patients

- Drawing boundaries for yourself as a patient

- Maintaining a sense of self and positivity

- Your tips on how to minimize “scanxiety”

- How have you processed the loss of fertility from cancer?

- How has the transition been to survivorship?

- Ovarian Cancer, High Grade Serous Stories

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Sara’s Story on Video

How I Got Diagnosed

Treatment (Surgery, Chemo, PARP Inhibitor Clinical Trial)

Navigating Life with Cancer

First Symptoms

Tell us about yourself outside of the cancer story

I love activities — physical activities, outdoor activities. I have been a nurse for more than 15 years. I’ve always taken care of people, but my family is very, very important. I love to travel. I feel like everybody says those things, but I do.

I’m in the gym at least five days a week. Snowboarding — I skipped a couple of years and impressed myself with actually not face planting completely this past year. I’m completely down for skydiving, traveling, hiking, climbing mountains.

Whatever is going to be a new adventure for that day, I’m in for it.

What were the first signs something wasn’t right?

About a couple years ago, I had random sharp pains. We tried to figure out what they were. We couldn’t figure it out.

My mom had breast cancer, so I always veered away from hormonal birth controls just for that reason. Also, because I just didn’t feel right on them.

Eventually, I ended up getting an IUD placed. They do a one-month follow-up ultrasound, so they did that follow-up ultrasound and saw a cyst on there.

My doctor was like, “Okay. There’s a cyst. It’s a decent size. Let’s monitor it and see,” because I wasn’t really having symptoms.

Describe the follow-up

We followed it up six months later, and things were fine. My CA 125 level was still normal, but on the higher side.

Then at my one-year mark, she had done another ultrasound and had some concerns that it had changed. In hindsight now, if I had known more of what the ovarian cancer symptoms were, I may have been like, “Yes, I have had some bloating, or I have had some like unusual things as far as that goes.” But I was completely unaware of any of the symptoms.

Meeting with a gynecological oncologist

I went in with the fact that I didn’t really have any symptoms of anything. I did end up having to meet with the gynecologic oncologist for surgery.

He was more concerned. I think I still was very oblivious. I thought there’s no way that this was cancer. He’s telling me all of the possible treatments, like the surgery, the hysterectomy, all this, and that.

I’m like, “We’re having a cyst removed. I’m going back to work in three days. It’s going to be laparoscopic.”

Getting Diagnosed

When did you realize things were pretty serious?

I feel like I went in pretty optimistic. About four minutes after I got to pre-op, when they did a urine pregnancy test, it came back positive.

Then I was like, “That’s not good.” They had to do some blood work. They were trying to convince me that I was pregnant, and I knew very well that there was zero chance of being pregnant.

I knew that that was not a good sign. You don’t have a positive pregnancy test. A tumor can cause a positive pregnancy test. That’s when I started having the, “Oh, no. This is not a good situation.”

Describe the cyst removal

I was going to have the cyst removed. My doctor and I talked at length on what the plan was, and I had to go into it positive.

I knew that I had to go into it with my head on straight, so I had told my doctor, “We’re going to go in. We’re going to remove the right ovary. We’re going to do the cyst. Then we’ll make a plan from there.”

I was not willing to sign consent to have a hysterectomy. I wanted kids still. I hadn’t had kids. I was very much trying to control what I could control, and he was very much trying to lay out the facts of things.

The doctor finally said, “Okay, we’ll do surgery,” because he was still concerned about this positive pregnancy test.

What do you remember of the surgery?

I didn’t go into the operating room (OR) until July 3rd, and it was late at night. We didn’t go until three o’clock at night because they had to wait for the surgeon to come out, talk to me, and everything.

We went in, and I was in there until about nine or ten o’clock at night that night. I ended up coming out of the OR and was immediately admitted just because it was a long surgery. I stayed in the OR for so long.

We also didn’t really know what’s going on at that point.

I woke up, and I just had some small, tiny laparoscopic incisions. I was like, “Is this still a cyst, or we don’t know?”

You heard your diagnosis by accident

When I was in the wake-up recovery room waiting to go to my room, I heard the PACU nurse call report up to the floor and said, “I have a 34-year-old female with metastatic ovarian cancer.”

Now, I’m completely out of it, have no idea what’s going on, and I’m the only person in there. It’s nine, ten o’clock at night in the recovery room. There’s nobody there. It’s me and the nurse. I’m sure he didn’t want to be there.

That’s when I was like, “Oh, this is why we are staying the night. This is why we are not going home.”

He just closed up surgery after taking out that cyst and said we would have to talk about it. I ended up getting admitted to the hospital. Then my family was still all there. We went to the room. I broke down a little bit and was like, “It’s cancer. It’s cancer. It’s cancer.”

No one in my family really knew about the cancer because I told my doctor he wasn’t allowed to tell my family until he told me. I was the medical one, and they didn’t understand, so they didn’t know anything.

They weren’t even prepared for me coming out to OR to start telling them that I had cancer. They weren’t expecting that either because I hadn’t talked to anybody. I had just heard about the cancer myself.

Then my doctor came in the next morning, and he said, “We have to make a decision. We have to wait and see if it is cancer. If it comes back as this kind of ovarian cancer, we can just do chemo and stay the course. If it comes back as this, then we have to go back for more surgery.”

We just had a waiting game at that point.

Processing the official cancer diagnosis

On July 4th is when I found out it was cancer. Up until that point, they had done a lot of work with my bladder. I couldn’t pee. I had to get a Foley catheter put in; my electrolytes were all off. I was a disaster on July 4th.

How did you handle those first days in the hospital?

I was very much not myself. I wanted out of there, and I wanted to escape. I’d let myself do what I wanted to do. I was like, “I’m going to go for a walk. I’m going to do whatever.”

My big thing was I needed to get out of my room. I needed to get out of that hospital room.

We had a big courtyard in the hospital that I was able to go to for a long time, and I honestly spent probably the entire July 4th out there with my Foley catheter hanging out, not caring, because I did not want to spend any time in that hospital room.

I had lots of visitors come in throughout. That helped a lot. I had tons of visitors come in and out. I was still on a full liquid diet for many more days.

Getting the full cancer diagnosis

On July 5th, my doctor came in and was like, “We’re going to keep you. We don’t know what’s going on, so we’re going to have you stop eating. I’ll come in, and I’ll talk to you about things.”

He came in finally at 5:00 p.m. and told me that I had clear-cell ovarian cancer, high-grade. That’s when I just straight broke.

I’m one of the rocks in the family. I’m the medical one. I know what’s going on for the most part. I’m the one who’s going to support the family, but I broke.

I completely lost my mind. I ripped off my shirt that I had on. It was down to a bra and shorts and just basically screaming and crying.

It’s funny now because at the time, I never wanted to put myself back in that spot because it was when I just broke. My whole family watched me. My whole family didn’t know what to do. No one knew what to do with me. I was completely irrational. I didn’t want anyone touching me.

My cousin had been there just visiting, and he was getting ice packs for the nurse because I was sweating. It was so hot.

Finally, I almost was like, “Okay. I just needed out of that room.” I went and found my nurse assistant, and I was like, “You need to dump this Foley out. I need to go for a walk. I need to get out of here.” I just randomly wandered the hospital at that point. I just needed to get out of there.

Treatment Decisions

How did you break the news of the cancer diagnosis?

I had a very close group of friends. My family was all there. A lot of my friends knew I was going in for this cyst removal procedure. They were aware of that.

I didn’t really tell many people about it just because I didn’t know. I didn’t want to be like, “Okay. I’m having an ovarian cyst removed, and I need attention.”

I’m very much someone who is very independent, so I didn’t want to go there with people. Once I found out that it was cancer, I started to tell some people. Obviously, the news trickled down through my family.

After I had my major debulking surgery, one of my best friends started a GoFundMe for me because I live alone with a single income. I was going to be out of work.

She typed up a story, and it got out really fast through that way. I ended up having a blog at one point just to take it away from my Facebook.

It goes back to the whole issue of control and the fact that I didn’t want cancer to be everything at that point. I was still trying to be in denial as well.

Tip: bloging helps prevent repeating information all the time

The doctors would say stuff to me, and I would have to explain it to my family. Then it’s like, “Okay. Now, I’m just going through it over and over again multiple times.” I ended up being like, “Okay. This is where I can put updates, and everyone can look there.”

My mom would try to do some things, and then I’m like, “Just send anyone there.” Everybody goes there. They can read there. They can follow there.

I had so much love and support. It was great, but it was also so overwhelming, where everybody wanted to know how I was. I was like, ‘I actually don’t know how I am.’

My best friend, Courtney, was very helpful with going through this group of friends, just trying to keep them in the loop. My brother was great. My mom was great.

There are so many people who just were great to take pods of people and keep them informed, helping the information trickle down. Eventually, I don’t even know if I eventually just blurted out on Facebook and said it, or if it just got to enough people and that’s how they found out about my cancer.

It was a weird time frame, especially since we didn’t think I was having surgery, and then everyone’s like, “Oh, you had surgery? Oh, my God. You have cancer. When did this all happen?” I was like, “Well, I didn’t think it was cancer either.” I didn’t want to bring that attention ahead of time.

Did you consider getting a second opinion?

I did not consider getting a second opinion. I went to Karmanos Cancer Institute in Detroit. It’s basically connected to the hospital that I work at.

I work in the pediatrics [department] and across the courtyard that I spent my entire time I was in the hospital. It was actually funny that I was walking around with a Foley catheter in front of my colleagues.

I would walk there. It just was the first place that I knew. I had gone there for my mammograms and all that stuff because I started getting mammograms so young because of my mom.

My OB-GYN recommended them, and then someone else recommended them in the beginning when we were just trying to look for someone.

He encouraged me to get a second opinion. He said, ‘If you want to get a second opinion, go get a second opinion.’ My only other second opinion would have been through a main hospital.

I honestly think having a cancer center made a huge difference on a lot of things. I see a gynecologist and oncologist. He runs my chemo. He runs my treatments. He runs all my stuff.

In the beginning, was I super overwhelmed? Yes, but at that point, I have cancer. It’s like when I first was going in for surgery, I’m like, “Oh, I may never see you again.” I kept playing dumb.

I just started researching what the treatments were. There wasn’t much of a difference. Since then, I’ve established a relationship with my doctor. From follow-up visits, I’ve established quite a relationship with the staff there and everyone else there.

Importance of good relationship with doctor

My own physician gave me his cell phone number the day I was diagnosed in the hospital. He said, “If you need anything, you can text me anytime.” We have a really good communicating relationship.

If it were to come down to later down the line, if I were to have recurrences or something like that, maybe I would go somewhere else.

He’s fairly young as well. I feel that he’s going to stick with me for quite a while, so that’s nice.

I do think second opinions are great for some people. You have to trust your physician and your team. You have to have that communication. Everybody’s different. Everybody has different personalities.

In the beginning, I was like, “Maybe he’s not good for my personality,” but then we’ve grown on each other where I just have trust in my team.

You’ve got to be able to trust them — not even that they’re going to do the best thing for you, but that they have your best interests in hand. Sometimes, they’re going to tell you no, and that’s because it’s in your best interest.

Debulking Surgery & Recovery

How did you make the decision to pursue a debulking surgery?

I knew that I wanted to get out of the hospital. Again, I’m a firm believer that you need to have communication with your team.

You need to advocate for yourself. I was like, ‘What’s going to get me out of the hospital faster? What’s going to have a faster recovery?’

I had talked to my doctor about that, and we talked about doing a nerve block versus an epidural at surgery time because I was like, “An epidural keeps me in the hospital longer. A nerve block could be less.”

The surgery involved making a giant incision right below the rib cage, all the way down to the pubis bone, and opening up and taking out what needed to be taken out.

Sometimes I would forget that I had this major surgery, because it is major. Everything’s taken out and put back together. They looked at things. Once you’ve had surgery, you see the actual incision. You don’t see what they’ve done on the inside.

Self-advocating for more anesthesia pre-surgery

I was very firmly telling them before surgery that I didn’t want to remember going into the operating room. I remembered going into the operating room my first surgery. I remembered it was just cold and sterile, and I was alone and scared.

I begged the anesthesiologist to give me some more medicine to keep me in la-la land before surgery. Again, a little bit of my control just wanting to not be there at that moment. I feel like a lot of it was just trying to escape those moments.

Describe waking up from the surgery

My surgery was seven hours long. The next day, I got back out of the operating room. It was probably ten or eleven o’clock at night when I got back to my own hospital room.

I ended up waking up in the recovery room with no nerve block, not any pain medication on board. They thought I was too sedated, so they didn’t do it.

I was in excruciating pain from not having that. I still do not regret the fact that I didn’t get an epidural. Once the nerve block worked, it was really, really good.

As a pediatric surgery nurse, I knew that number one was I had to get up. The next morning, I woke up and was like, “We have to walk. I need to get in my normal clothes. I want out of this gown.”

I ended up coming off pain medications pretty fast. I ended up walking as much as I could. I was just moving around. As soon as I could, I got moving.

Transitioning to recovering at home

My nurses were great. I ended up having to go home with a Foley catheter. That’s when I feel that a lot of things hit home.

The pain was bad from the surgery, but I never felt that it was so bad. I was pretty physically fit beforehand. I felt strong. I knew that my arms were strong to help me get in and out of bed. My legs were strong to get me in and out of bed. I just tried to not use my abdominal muscles.

Just from being a nurse and knowing positioning and stuff like that, it was really easy for me to get moving. The fatigue was something that started hitting at that time, where I’m like, “I’m going to walk down the hallway. I want to take a nap now.”

Dealing with the mental recovery

I remember I had talked with my doctor as soon as I was diagnosed and said, ‘I’m not going to be okay. I want to talk to somebody.’

They sent a psychologist in there. She may have come in the day before surgery. She came and found me the day after my surgery, later on that day. I was just crying. She asked, “What is wrong with you?” I’m like, “I’m tired.” She’s like, “Why don’t you sleep?”

I had been trying to entertain everybody around. It’s hard to take care of yourself. You forget that you’re a patient. You’re like, “Okay, there are people here. I need to stay awake.” My family was like, “Just sleep. Just sleep. Just take a nap.”

It was very hard for me to step back and be the patient and be like, “Oh, your body needs this. Your body needs rest.”

Then the next day, I was sitting there just sleeping all the time. I felt much better. I felt that there was so much of me that knew what to do, but then so much of me that needed to be told what to do.

That’s where my two worlds were clashing, where I was like, “I want to be better. I want to be home.” Then the other part of me was like, “You’re not there.” It was this kind of meet-in-the-middle situation after surgery.

How long did surgery recovery take?

As far as recovery from surgery, it took two months, if not longer. I felt really good at my three-and-a-half-week post-op visit with my doctor.

But then I started chemo about three weeks after surgery. It was almost like, “Now, this is just happening.” Probably 14 days after surgery, I was much, much better.

I was stubborn. My sister-in-law had a bridal shower. I got out of the hospital Friday. The bridal shower was Saturday, and I went.

My brother had taken such good care of me. I was so excited for their shower. I needed to be there.

Do I regret it? Not at all, but it was so much. It was very exhausting, but I did it, and I’m so happy that I did do it, even though I was miserable the entire time.

About 14 days after, I was able to get in and out by doing things, moving around. The Foley catheter was gone. Things were much, much better.

When could you resume “normal” pre-surgery activity?

As far as working out, my doctor said I could start three, four weeks after surgery. You can wait longer.

I had a five-pound weight restriction from surgery until six weeks. I was only allowed to lift five pounds until six weeks. I also had four weeks of no driving.

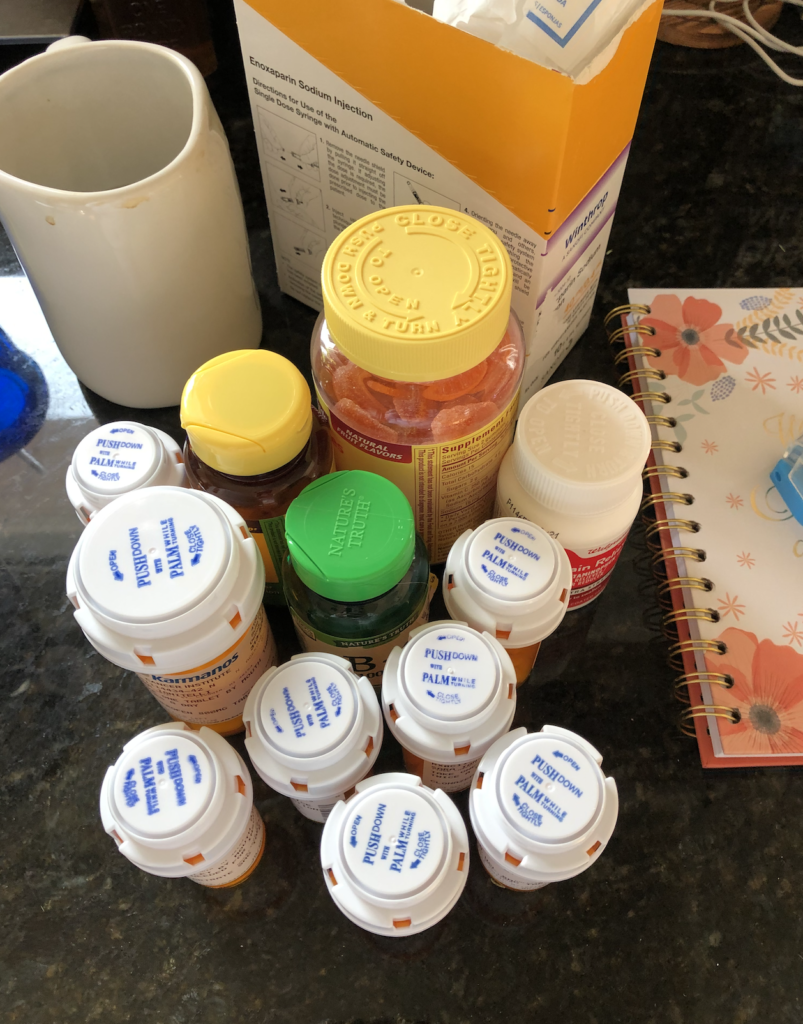

As with most people, they know that narcotics cause constipation. I weaned myself off the narcotics as fast as I could. I went to just Motrin, Tulane, Tylenol. I didn’t want to take any medicine.

Every single time I told my doctor, “Can we stop taking this one? Can we stop taking that one?” He’s like, “Just let it happen for a while.”

At around four weeks, I started light jogging. Once he gave me the go-ahead, I started to lift weights again. It was probably at least three months until I could do a sit-up. I would do sit-ups, and if I could do them, the next day I was in excruciating pain.

Everyone would be like, “You did have a major surgery.” I had to be reminded all the time, because I was so mad that everything else was starting to work and that was not working. I played the whole game that I tell my patients, “If it hurts, don’t do it. If it’s sore, it’s okay.”

I went with like, “Okay, I just can’t do abs.” Once a week, I would try to do it again, and then I would be like, “No, not time yet.” I played around with that. I probably would say at about three months I was fully surgically healed. At about six weeks, I was feeling much more like my normal self.

How did you manage the Foley catheter

The first surgery happened, and they had to do some stuff where they had to check the bladder. Part of the cyst was against the bladder. My urethra was basically pretty swollen.

The next day, I was in and out of the bathroom peeing enough. Then I just didn’t feel that I was peeing enough. They asked me, “How are you?” I was like, “I don’t know if I am emptying my bladder all the way.”

They did a bladder scan, and they were like, “You have an ova leader in your bladder right now.” I was like, “Oh, I don’t really have to pee that bad.” I went to the bathroom, and I peed literally like 800 milliliters, and they bladder-scanned me for leader cells.

They have no idea how much I had in there because I’d just gone to the bathroom. They were like, “You’re not emptying your bladder. We have to put a Foley catheter in.”

They talked about just doing a straight catheter just to do a one-time only to empty my bladder, but my nurse was like, “No, she’s had this surgery.” She pushed for me not to. It was probably the most embarrassing experience, being a nurse.

You’re naked from the waist down; you’re spread eagle. My nurse couldn’t get it. The charge nurse couldn’t get it. The resident came in to try to do it. They had to get a Foley catheter from the children’s hospital because it was so swollen.

Then once they got it in, it was not horribly painful. Honestly, I was really hyped up that it was going to be more painful than it was going in.

It wasn’t comfortable, but it wasn’t a devastating kind of thing. Then it was not bad because it was just like, “I don’t have to get up and pee. It’s great.”

I was just walking around with the catheter, and it was astonishing how much urine was coming out and the fact that I was not peeing beforehand by any means.

Then at surgery, my doctor decided we were going to keep it. At that point, they did change it out in surgery, but to a regular size one. It was not painful.

I was okay with this. I knew what it was. It was not going to stay permanently.

Processing the situation at home

It was when I got home with a catheter when a lot of things hit, like, “This is real. This happened.”

When you’re in the hospital, you have IVs, [and] you have all these things going on. You go home, and you’re like, “Wait, my home hasn’t changed, but I have changed.”

That was a lot. Even as a nurse, I wasn’t prepared for that. I didn’t even know that kind of thing. I knew that you go home and it’s harder, and I always just thought it was because you didn’t have the help there.

It wasn’t that I didn’t have the help there. I was totally fine to get myself in and out of bed and do all of my things on my own. It was more that I went home, and reality hit the day I got home.

Chemotherapy & Side Effects

Describe the chemotherapy regimen

My doctor decided to do carboplatin and Taxol. I did six cycles, but since it was weekly, I did carboplatin every three weeks and then Taxol every week.

Starting out, I’d do the both of them, then the next two weeks I would just do Taxol. Then the week after those two were done, I would start up with the carboplatin again.

My carboplatin and Taxol weeks were miserable. It was like my double chemo week. I was there much, much longer. It was the week that I would get the sickest.

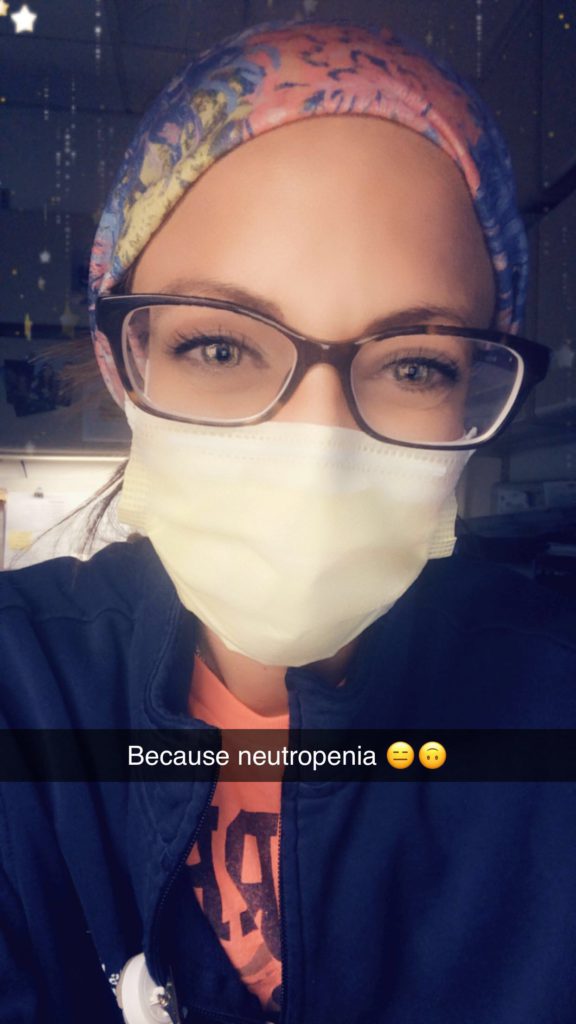

Dealing with having to delay chemo because of neutropenia

After Round 2, my counts had gotten really low. My absolute neutrophil count (ANC) is what they were monitoring. It was very, very low. I had to skip a week, and then I came back the next week and my numbers were exactly the same they were the week before.

When you go to chemo and then get told you can’t get chemo, it is devastating. You’re ready for chemo. You’re ready for the battle of chemo, and then they tell you to go home.

For me, I also had cold caps. I had two people there who were going to help with cold caps. They’ve taken off work. They’re here for me today, and I have all this dry ice for the cold caps. We’ve dragged this giant thing in here.

Then the staff says I have to go home. I’m like, “No, no, no, no, no. I can’t go home. I need chemo.” I would literally point out to someone in the chemo suites who was lying there half asleep.

I’m like, “They’re getting chemo. Why can’t I get chemo? I’m walking in here just fine.” It was hard. We ended up adding on some Neupogen. I couldn’t do the Neulasta because I was getting chemo every week and [with] Neulasta, you have to have more of a break.

We started adding on Neupogen. I would get my double chemo, and then the next week I would get just the Taxol. Then the following week, I would get my Taxol and then the Neupogen.

When did the side effects get the worst?

My chemo infusions were always on Thursdays, and then Friday I felt great. All the steroids and everything would kick in on Friday.

Saturday about noon, it happened. I would go to the gym Friday, I would go to the gym Saturday morning, and I had to get home by noon because I would turn into a pumpkin. That’s when I needed to go and not come out of my house for three days.

I would go home at noon on Saturday, I would feel miserable, and then I worked on Mondays. I was still able to work but not in the best shape. By Tuesday, I felt good, and then unfortunately, by Thursday I was back in the chemo chair.

The weeks that I just got the Taxol was fine. I was tired and wasn’t feeling the best, but I never was really bad. The following week, I got the Taxol, and then I got the Neupogen.

Describe the Neupogen shots

Neupogen is like giving yourself the flu. You had to do these shots. I did a shot once a day. Being a nurse, I’m not able to give myself shots.

I had many people lined up to give me shots. I had my nurse friend stop by. I had to do heparin after the hospital for about a month, then the Neupogen. I never wanted to give myself an injection.

I had an amazing group of friends and family. My brother, who is an engineer for GM, learned how to give shots in the hospital because I was like, “I can’t do this.” He would come to do my shots, and we would do my shots in public. I was like, “At this point, I don’t care where we’re doing them.” We would have a family dinner, and he would be like, “Okay, let’s do your shot.”

I just never had to do my own shots. It was basically like you had the flu. I would typically do Neupogen Friday, Saturday, Sunday, so pretty much by Saturday afternoon I was like, “Okay, this is terrible.”

List all the chemo side effects

My biggest side effect was fatigue. That was number one. When I had the double chemo, it was nausea. Normally, I didn’t really have an appetite with the carboplatin and Taxol. I was super nauseated.

There were only a couple of times when I actually got sick. I’m not a person who typically vomits, and so I wanted to do everything not to.

How did you manage side effects?

I pretty much ate blueberries and goldfish my entire chemo because they were the only foods that I liked and tolerated. I kept my Zofran on hand, and I would make sure that I took that around the clock, especially as soon as I started feeling nausea and wouldn’t eat.

I made a plan with myself that every time we had a different round, I tried a new food. Every single time, it failed. Nothing new was going to work. It was just the chemo.

The first round, I focused on staying hydrated and did my best to drink some water. If I was not going to eat, I’d try to drink water and hoped I’d be okay.

The second round, I realized that didn’t work that well, so I would try to eat even though I just wasn’t hungry. I wasn’t thirsty, but if I could force myself and not throw up, maybe I could keep myself somewhat doing okay. I ended up just being like, “If I can just drink some fluids, I’ll keep myself going, and I just have to make it to Tuesday.”

I still worked out. I didn’t work out on the night before chemo and chemo days. Basically, four or five days a week, I still worked out, and I worked 30 hours a week.

I had to work. I needed the money. I needed to financially keep myself afloat. Working out was something that was mine, so I was not giving that up.

Neither working or working out were done very well. My work was very generous with being understanding that I was more tired, letting me be a little bit more “lazy” with things.

It was more that I am a high-energy person, so even some of my friends would be like, “Okay, well, you’re just normal energy now.”

I was still functioning, but no one really cared because I was still doing things at work. I felt like, “You have no idea the energy it is taking me to do those things.”

Did side effects get better or worse?

The first chemo, I was very surprised and like, “This is easy. This isn’t that bad.” In hindsight, it’s funny to me because I feel that that’s where everybody is. You’ve never gotten chemo. Your body’s adjusting a little bit.

Then it’s Round 4. I’m like, “Oh my God, I basically might be dying. What is this?” It’s much worse. You still try to play the game. You’re like, “I’m not that sick. I’m not that sick.” It gets harder.

My last three cycles of chemo, I had one week when I felt fair, and then I was so tired. It’s just like a snowball effect I felt from the third round on. It got harder and harder.

Then the counts were always low; everything was always low. I remember right before my second-to-last chemo, I blew my nose, and it was bloody because my platelets were non-existent. I was pale. I was thin. I’m like, “I want to sleep anywhere, but I’m not sleeping. I’m just awake all the time.”

Describe your work schedule during chemotherapy

I worked Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday during chemo. I did chemo every single week.

I worked the first three days, and then I would work out. I controlled when I did these. Everything else was up in the air.

Working and working out were ways to feel “in control”

The way I exercised control was to make sure I was eating as healthy as I could when I wanted to. I did make sure that I had certain foods in my house.

Working out was a big thing for me, where I had control of what I did with this hour of mine. No one was going to tell me how long to be here. No one was going to tell me what to do. No one was going to tell me how to do it.

I’m doing whatever I want. If it’s just riding a bike for 15 minutes, I’m riding a bike for 15 minutes. I very much think that there’s something that you need to control because you’re not going to control your schedule.

You’re not going to control when you’re going back to the doctor; you’re not going to control your medication.

You lose complete control of everything that you have in life. It’s very overwhelming, and it’s very fast. One minute, you have control. I was going into the hospital totally fine.

The next day, I have a Foley catheter, I’m getting IV replacements, and I have cancer. It was just 12 hours.

Managing Hair Loss

Preparing for chemotherapy hair loss using cold caps

I had not really known much about cold caps. Funny enough, one of my friends at work and I were talking about the fact that I had to have the surgery. I was like, “What if it is cancer?” Like, “Oh my God, we actually probably should think about that.”

She’s like, “My aunt did cold caps. We’re going to keep your hair. It’s going to be fine.” I never heard anything about cold caps. Somehow, I feel like someone put it in my head. I love my hair. I hated it when I was younger, but I love my hair. It’s thick, and it’s exactly how I wanted to do it. It works how I want.

I’m like, “I cannot lose my hair. I need to keep my hair. Okay, we’re going to do that.” But you also don’t know if it’s going to work.

My doctor had convinced me that it wasn’t going to work. He didn’t really have anyone that did it. It was more of a breast cancer thing that people had cold caps for.

Even the cold caps company told me that they don’t know for the most part about some chemo. Some chemos they can say they work on, but other chemos, they don’t know.

You have to wear the cold cap an hour before chemo starts, for maybe two hours after, and then the entire time during the infusion.

My brother’s wedding was going to be in the end of September. I did not want to be bald for his wedding. He had been my rock this entire time.

We have so many things that now we can laugh about during chemo, in that timeframe, like, “I can’t be bald for his wedding.” I wanted to find a way. I wanted to have something in case it happened.

For the most part, your hair falls out a little bit at a time, and then it’s gone. I didn’t want to wait until it was gone to have to be like, “What is going to happen?” I wanted to have a plan.

Describe the wig shopping experience

I went to an old lady wig shop, and it was horrible. I was like, “This is terrible. This is not going to go well.”

I didn’t get much help from my doctors. I didn’t even ask my doctor, but I did ask the nurses there where I should go. They were like, “We don’t know. Just go somewhere.” I was like, “Really? You’re an oncology office. You don’t have these options?”

I ended up finding this place called Wigs for Kids. The owner started out doing wigs for adults, but then switched over to doing kids. She was a godsend and amazing.

I went in there, we tried on a bunch of different wigs, and she helped me with the wig that I picked out that was almost identical to my hair. In the pictures that we had taken with a wig on, no one could tell that it was not my hair. The wig shop owner said she would hold the wig until my brother’s wedding, and then we would go from there.

My brother’s wedding was about eight weeks into chemo. I was like, “Okay, I’m either probably not going to have hair then, or it’s going well.” She said she would keep it until my brother’s wedding so that that way, worst-case scenario, I did have some kind of hair for his wedding.

That’s where I had that on the back burner. She was just a great woman who helped me with making sure that I had disposable makeup stuff. That way, I didn’t get any extra infections.

I ended up having some therapy sessions with their social worker at Wigs for Kids. It came a little bit full circle. I didn’t actually ever get a wig there, but I ended up having some therapy sessions there. I made a donation to them. I had just landed there. It was an amazing place to have landed, though.

Cold caps helped you keep the hair on your head

I lost all my hair besides my hair in my head, probably about 25% of my hair. It was still very nerve-racking all through chemo when I would wash my hair, and then there’d be hair coming out.

I’m like, “Oh my God. Is it going to be too much?” My hair did decently thin out a little. With the cold caps, I could only wash my hair in ice cold water. I would have to take a regular shower, then get out of the shower, hang my head over the sink, and wash it with ice cold water.

No blow dryer, no heat, no nothing. At some point, I was like, “This is worse than anything, than just shaving my head at this point.”

»MORE: Patients describe dealing with hair loss during cancer treatment

Clinical Trial

How did you start a clinical trial the following month?

I actually skipped my very last chemo, which was just a Taxol dose. I missed my last dose because I showed up, my platelets were like 30, my counts were non-existent.

My doctor decided the last Taxol was a third of a dose, I had done all the doses, and I could be done. He said, “You don’t need to come back. You’re just done.” December 5th, I finished chemo. December 12th is when I was supposed to get my last chemo.

Before that happened, we had talked about what the next step would be. For high-grade clear-cell ovarian cancer, there’s nothing. It’s a wait-and-see kind of game.

My BRCA genes were negative. It wasn’t that we were going to go to this route because of that. My genetics, everything was normal. There was one gene of unknown variance, but they don’t think that that means anything and obviously don’t have a plan for that one.

So it was very much a wait-and-see kind of game. Then the trial nurse who works with the hospital came and talked with me to describe a trial that was going on. They were taking people who were BRCA negative and trying to see if PARP inhibitors and immunotherapy were going to help them.

The key was that you had to start it within 60 days or so of chemo ending. You had to start pretty fast after chemo ended.

They were very much, “It’s up to you. You don’t have to. You don’t need to do this.” For me, I couldn’t do nothing. Nothing drives me like off the deep end. I have researched so much; I have seen what the statistics are for ovarian cancer. I can’t do nothing.

Whether it helps me or helps somebody else, I needed to do something. I was like, “Okay, we’re going to go with a clinical trial.”

Describe the preparation ahead of the clinical trial

Chemo ended on the 5th, but then the 12th I was there. They said to come back a week later because my labs were still terrible. My doctor said I needed Neupogen again. My counts had to recover to start the trial. At that point, it would be around Christmas, the New Year,, and I wanted to meet this new deductible.

I was all wet behind the ears, trying to make sure that we got everything done. I needed to get EKGs, my Neupogen, and my urine samples all ready for the trial because now we had the holidays in the mix.

I did two or three rounds on Neupogen after chemo ended just to get myself back to a normal count level so that that way I could start the trial. My CT scan was at the end of chemo as well. The month of December was jam-packed full of everything, including the holidays.

Luckily for me, at some point during early chemo, probably right after Halloween, I had put the Christmas tree up. I was like, “I might get sick. I need this tree up.”

I went Christmas shopping ahead of time, so I didn’t have anything I needed to do later. I was very much like, “I don’t know how sick I’m going to get, so I need to get all my ducks in a row so that that way, if I’m sick, I just don’t have to do anything.”

I very much was controlling the situation, where I would make sure that I wouldn’t be a burden on someone else. I wanted to make sure that everything was taken care of so I wouldn’t have to stress about it later.

Learning how not to put things off

Another thing that I feel is very important is that if something is weighing heavy on your brain, whether it’s, “I need to do Christmas shopping. I have a birthday party in a month and a half, but I don’t know how I’m going to feel,” do it now.

Do whatever you need to do now. I did all my stuff, so I was able to just go to my doctor’s appointments and rest. When chemo ended, a lot of the stuff I did for everybody else. My family wasn’t coming to appointments as much anymore because I didn’t need to do cold caps.

I would go from work over to the infusion center that was just across the street. I would get my IVs. It’s weird; I was like, “I’m a nurse in my nurse outfits.” Then I’m going over here, and I’m the patient. I had some issues sometimes being like, “I’m the nurse. I’m not the nurse; I’m the patient. I’m the patient in the morning and the nurse in the afternoon.”

It was a very weird mix. I was in the doctor’s office once a week, if not every two weeks, until I started the trial.

Describe the clinical trial

It’s a twice-a-day pill that I take, and then the infusions are once every 28 days. We started with getting the pills for about a month. After two weeks, they checked my labs. Then we started the infusion. They checked my labs again.

Now I’m at the point where I see my doctors once every 28 days. My CT scans are spaced out. Initially, they were every eight weeks, and I think they’re every 12 weeks now. They’re going to space out a little bit as well until we finish the trial, which should finish in either December or January this coming year.

They’re PARP inhibitors. It’s actually funny because I really don’t know exactly how to pronounce it. Rucaparib (Rubraca) is the one PARP inhibitor. It’s not the one that most people are on, and I actually have zero clue how to say the other one. It’s funny, my doctors would probably be like, “Really?” at this point because they say it so much.

What drove you to participate in the clinical trial?

If I can be a voice, I want to be a voice. I feel I didn’t find anything on the internet with someone like me.

I even asked my doctor. I said, ‘Where do I stand in a book?’ He’s like, ‘You’re not a book.’ He told me I was not going to find girls like me, women who have ovarian cancer at my age.

Somehow, I have found a giant community, and it’s great. I wanted to make sure that people had someone to reach out to or someone to know, someone who has been there in their shoes.

Like I said, if it doesn’t help me, then it shows that this doesn’t work for someone else. My fate is my fate.

Obviously, I plan to live until I’m 85. If I have to do this miserable treatment that’s making me still tired, still all this and that, and see my doctors once every 28 days for the rest of my life, so be it. It’s a lot. It’s one of those things that’s just part of my life now.

Knowing about the drugs in the clinical trials

Some months there are a lot of appointments; some months I don’t see my doctors but once every 28 days. There are stages of clinical trials. There are some clinical trials where their meds are brand-new and they’ve never tried them on anybody.

The PARP inhibitors, they’ve tried it. They just haven’t tried it with certain patients. The IV infusion is stuff that they’ve tried with different kinds of cancers or different kinds of autoimmune diseases.

They knew these side effects of these medications. They knew what these medications would do [and] how people would tolerate them. That made me much more comfortable with being like, “Okay, let’s just do it.” I had an idea. It wasn’t a very brand-new drug that I didn’t know anything about.

Describe the clinical trial drug side effects

Summary: nausea, gastrointestinal problems

The side effects of the oral medication was a bunch of nausea in the beginning. I was just getting back from not having nausea, so [with] that, I was like, “Oh my gosh, now I’m taking Zofran again.”

Nausea is, one, decreased appetite, and then GI upset is a big one, a sour stomach kind of thing. Fatigue is another big one. Every single time I went to my doctor, I’m like, “I’m tired. I’m tired. I’m tired.”

They had told me that someone else was on the same trial, and she slept for 20 hours a day. They had to decrease her dose.

They literally don’t care. Because I’m still going to work and I’m going to the gym, I’m like, “You have no idea. I’m so tired.” It’s not even the kind of tired where some days are better than others. It’s more of a tired like, “I just don’t want to do anything. I want to sit there and stare at the wall, and I’m totally fine doing that.” It’s more of that.

Even in the gym, I’ll go to the gym and feel every day the gym is the same new day. It’s the same first day of it. I’m trying to work out; I’m trying to run. I’m not building any endurance. I’m not building any muscle. I’m just doing the same thing for the first time every time.

Managing the side effects

It does get very frustrating for me, where I’m like, “I’m not making progress here. Why am I not? Some days I feel better.”

I’m trying to balance things out, where everyone’s like, “It’s the new normal. You’ll feel better after you’re coming off of it.”

There are more hot flashes, which are part of postmenopausal, surgical menopause. It’s a new lifestyle, but I also firmly don’t want to say it’s my new normal because I feel there are certain things that are triggers to people, certain things that are not to other people.

To me, telling me this is my new normal — I don’t want that. This is not my new normal, because this isn’t going to stay.

Hopefully, as the years go by, things will get even better, and I’m hopefully not as tired. I pick back up my energy a little bit. This is the season we’re in.

Why did your doctors say they wanted to pursue the clinical trial?

Going on this medication, I was hoping for one or two things. The PARP inhibitors are approved for some types of ovarian cancer, and sometimes that will help stop the recurrence from getting worse.

What I hope the immunotherapy does is either gain me two years with this trial before we would have a recurrence, or hopefully I don’t have the cancer come back.

There are a couple of different options. You’re either going to be on it until the end, or you’re going to be on it until I decide [to end it]. I could tell them tomorrow, “I don’t want to do it anymore,” and it’s no questions asked, I’m done. If I wasn’t tolerating it and my doctor felt that it was not safe anymore for me, he would pull me out of it.

Or if I had a notable recurrence, they would probably pull me from the study and say, “Obviously, this is not working.”

The nature of ovarian cancer and recurrences

With ovarian cancer, it’s like a 70% chance of recurrence. It doesn’t matter what kind of ovarian cancer you have. It’s more of being stage 3. It’s a very high recurrence rate. It’s a very aggressive cancer, especially being high grade.

With mine, I’m going to more likely develop a tumor that comes back, whereas with low-grade ovarian cancer, there is more of a chance of having these spots and lesions everywhere, slow-growing, and all of a sudden you have bad disease.

Ovarian cancer is very aggressive. It’s very hard to determine it and detect it. There’s no, “Just do this, and you’re great,” or “Just have your ovaries removed, and you’re not going to get it again.” I feel it’s a very underfunded, under-researched topic. I didn’t know anything about ovarian cancer beforehand.

Then [when] you delve into it, it’s like, “Oh, my God, this is very serious. Why do we not know more about this?” It is crazy.

For me, it was do nothing or do something, and I’m like, “We can do chemo every three months or something like that and just do a little bit of chemo, every once in a while, just to keep things at bay. I’m fine with that.”

Quality of Life

The importance of self-advocacy

If something’s not right and you know, “Okay, this is not my normal.” You have to know your body. I think that that’s number one with anything. If your body or if something happens where you just don’t feel right with what the doctors decide, push for more answers.

I think almost all ovarian cancer is diagnosed at least six months after the first symptom starts, which is crazy because most women are just told that they have bowel issues, irritable bowel this and that, and they’re pushed off. A simple once-yearly pelvic ultrasound could literally change the astronomical progression of this disease.

It’s diagnosed typically at stage 3 and above, but if it’s found smaller, just on a routine screening, there could be so many different things that would happen for women.

You advocated to get paperwork for your own records

I found my doctor in the hallway and I was like, “You need to give me the pathology report. I need to see my name on that piece of paper that says that.”

Still to this day, he gives me every single lab work. I need it all. Some of the things that you have to do for yourself, you have to do. That’ll make you feel better.

Not that I want to say it’s gotten easier now, but in the beginning I wanted every single piece of paper, every single thing that had my name on it, my lab work. I wanted to know what they were doing. If you’re giving me blood, if you’re giving me this, if you’re giving me electrolytes, I want to see why.

Half the time, I didn’t read any of it. Half the time, I just put it in a folder. The folder was full of lab work, and I just didn’t know what I was going to do with it at any point, but I needed to have it. My doctor just let me do that, which was good. I’m very thankful for that.

The power of being an informed, engaged patient

It’s important to have that information to understand. There were times in the hospital when I was just letting whatever happened happen, because I was very much confused by the whole situation and overwhelmed.

But when it came time for chemo, I would get my lab work, and I would see that my counts were really low, so I would need to be more careful. Not that I wasn’t listening to my doctors, but me having the medical background, I’m like, “Oh, we are really low this time. We need to be really careful.”

My doctor was very easygoing. Mainly, his things would be, “Just don’t be dumb. Keep washing your hands. Don’t touch the people that are sick. Wear a mask.”

I’ve been wearing the mask since back in 2019. I’m over the mask at this point, but even with my nephews, I wouldn’t kiss them on the face. My doctor said, “Still live your life and do those things.”

But when it came to even my electrolytes, he was like, “Please, don’t go home and do what you did in the hospital and drink just straight water.” I’d drink about five liters of water a day at the hospital because I wasn’t eating. Then my electrolytes were complete crap.

So then I knew during chemo that I needed to have some kind of electrolytes or a smoothie. My whole thing was I need to control something. I feel that that’s very important to find something to control, and it does not matter what it is.

The need for more awareness about ovarian cancer

I don’t fault any of the women I know who have gotten diagnosed. I don’t fault any of us for not knowing.

As a woman, someone should notice that the Pap smears are not causing you to have any kind of awareness or any checking on your ovaries.

Many, many women are told when they’re younger, “Oh, it’s your periods are just heavy, no big deal,” or, “Oh, this and that.” I feel that it’s something that our gynecologists need to be much more proactive about.

I feel that every woman should know the symptoms of ovarian cancer. Since I have been diagnosed, even some of my friends feel bad and think, “Do I have it?” because there are very common symptoms.

Bloating, abdominal pain, pain during sex, irregular periods, change in bowel habits — these things happen regularly, but if things happen and they last for longer than two weeks, you have to almost be like, “You know what? I need to see a doctor.”

Finding your cancer community

Absolutely, you need to find someone who’s going through it with you. I also feel that you need to find where you fit. When I got diagnosed, I was like, “I’m going to need help.” I couldn’t find anybody who was my age and who went through it who didn’t have kids yet.

Everybody was like, “Oh, I’ve had kids,” “I’m here with this,” or, “I’m here with that,” and it was very hard for me to find someone whom I connected with.

I found some people who were older, and they were just angry about it. They’re like, “I was so mad. Any time that time of year comes up again, I’m very angry.”

I had a really hard time finding that. I ended up branching out to Instagram because Facebook was more my friends and family. There wasn’t very much outside of that.

Then with Instagram, there was a wider community. You were able to find more people. I slowly started to find some women who had ovarian cancer.

I actually had a girl — she had reached out to me from California — who had breast cancer at the same time. She was diagnosed about a month after I was, and she was doing cold caps. She and I connected really well. We were going through chemo at the same time, and we had this connection. She would be like, “Is this happening?” Then I realized that that’s what I needed.

I needed to have a give-and-take kind of relationship. I didn’t want to just sit in a room and be talked to. I needed someone who was with me in the same timeframe.

A key, important thing I feel as far as your mental health during this experience is to figure out what you need. Just because everyone’s saying go to a chat room, it doesn’t mean that’s going to work for you.

For me, it was actually being able to help her while she was helping me. It’s made a huge difference that I was feeling needed, and then I was still feeling like I could help her, but then she was helping me by validating a lot of things that I was going through as well.

Then slowly, there were more ovarian cancer girls. You start to slowly find them, especially the more you’re public about it. There are some girls whom I met who literally created an Instagram account just to find somebody to talk to. They have zero photos. At some point, they would connect with me. They’d find me because I was more verbal with my story. Then they would be asking questions. It’s sad. These women are scared to ask questions.

There’s my poor doctor. I’m like, “Okay, sexual health, let’s talk about that.” It is one of those things that I am not afraid to talk about with someone or with my doctor.

So I met a lot of great women on Instagram. I’ve done a lot of Zoom calls with different groups. Quite a few girls and I have formed this Instagram community, where we meet once every three to four weeks.

We pick different topics, then we’ll post different conversations about things like chemo and tips, like what do you use for chemo, what do you do for anxiety when scans come up, what do you recommend someone take to the hospital?

Number one, everybody’s like, ‘Get a seven-foot cord for your charger,’ which no one even thought about. It’s the best thing ever. You need a 10-foot cord to plug your phone in so that you can sit in your hospital bed and use your phone.

It’s a community where we can all learn certain things. I so wish I had this. I’m so glad that I’m part of this, but I so wish I had it when I had gotten diagnosed because I felt so very alone.

I was 34 years old, and I’m now going through medical menopause. Nobody understands that. Nobody in my community, my group of friends. Yes, Mom does, but I don’t want to talk to my mom about menopause.

And I don’t understand what my body’s going through, so it was very nice to be like, “Oh, you’re having this? I’m also having that. What did you do for that?” It was very nice to finally find somewhat of a community that was a lot less structured and a lot just more open.

The importance of having caregivers

My mom was there. She had gone through breast cancer when she was 34 or 33. She had gotten cancer around the same age as I was, so she was very much there for me. She was there at the drop of a hat. She went to all my chemos. My mom was great.

We did have some issues here and there because she was having a hard time dealing with it. I do feel that to a certain extent, some caregivers are dealing with it themselves, and they have a hard time.

My mom would try to lean on me like we always did, and there’s many times when we would get in an argument. I’d be like, “I’m sorry that my cancer made you sad.”

I’m pretty sure that everyone who gets diagnosed with cancer cries the whole first year they’re diagnosed. If you don’t, then I’m proud of you, but I cried the whole first year. There would be times when I wasn’t crying, and my mom would be like, “Yes, I remember this part,” and I’m like, “Okay, now I’m crying again.” There was a lot of crying,

I had my mom there for me, very much so, but then there was a lot where I had to set the boundary to say, “Don’t bring it up unless I bring it up.” Then there were certain things that she was able to go through with me, and she showed up for a lot of things.

My brother, who came for my cold caps, just did things for me. Honestly, I don’t know what I would’ve done without him. He just did things, and there were no questions asked. If I needed it or I mentioned it, it was done. In the hospital, I was sitting there, and I would get hot. He showed up with a fan the next day.

I came home from the hospital, and he put a ceiling fan in my house, my bedroom, so that I could have a fan in my room. I had asked for one years ago. While I was in the hospital, he put a fan up.

After my big surgery, he came every single day. His boss was amazing and told him, “You do not come to work on Thursdays. You go to your sister’s chemo.” He was there for every bit of it. He learned my injections. And he was never pushy.

Guidance on how to support cancer patients

That’s the thing that I think makes a difference. Send flowers to someone. Food is a hard thing for a cancer patient because you don’t know what they’re going to eat, when they’re going to eat, what they want to eat. Someone sent me egg sandwiches one time, and I threw it all away. I feel so bad about it, but like, “I’m not going to eat this. I live alone. I’m not going to eat it.”

Find something that someone likes and do it, like a card you send in the mail. I would get random cards from random people, and it made my day.

Also, trying to do things that aren’t chemo or cancer related. One of the nurses whom I met in the hospital I became good friends with, and she texted me one Friday. She’s like, “I’m off work today. Do you want to go walk around Detroit and go to this Kanye West concert?” So we went to this thing.

It was totally random. It was weird for me because I sat there being like, “Oh, my gosh. I have cancer, and no one knows.” It’s very nice to have people that still treated me as a whole and didn’t treat me as cancer. Even though it was 1,000% on my mind all day long, it was nice to have those moments.

Drawing boundaries for yourself as a patient

I do feel that you have to ask for help, but you also have to tell people no. There are days when I literally did not leave my bed for 24 hours, and my family would be like, “Why didn’t you tell me? We would’ve come over.” I’m like, “No, I needed to be alone. You’re going to stare at me. I don’t need you to stare at me.”

It’s very much of knowing yourself and knowing what you need as far as do you need someone there? Are you someone who needs somebody there, whether they’re doing anything or not, or are you someone who needs to be alone?

You have to have your core group and be able to say, “I need you now. I don’t need you now. I want you to come here now. I don’t want you to.”

It’s just a lot about self: knowing yourself and being self-aware.

Maintaining a sense of self and positivity

I remember I told the psychologist in the hospital that I didn’t want to hate my life moving forward. I didn’t want to lose my positive outlook. Many people are like, “Oh, I got cancer.” I see the silver lining in things. I enjoy the little things.

I was like, “Enjoy the little things. Enjoy the sunshine, sunrises, sunsets, these things.” I was always that girl, and I was so afraid of losing that person. I feel that I have worked extremely hard to maintain that person, where I did have a harder time with myself when I felt weak. I’d be like, “Why am I feeling so weak? I need to be stronger. I need to do better. I need to be this.”

Now I’m like, ‘Wow, I didn’t give myself enough grace when I went through this.’ I want to encourage more people that when you’re going through this, some days will be terrible.

Some days will be okay. Days that are terrible, you have to just let them be. You will be okay. It’s okay to not be okay.

One of my good friends told me that 7,000 times. “You do know it’s okay to not be okay today?” I’m like, “But I just want to be okay.” I fought it so hard. I feel that’s something that moving forward, give yourself grace.

I still have days. There are still triggers that happen. The triggers come, and I can’t control them. I don’t know when they’re going to happen.

Whether it’s a baby shower that’s brought up, and I’m like, “Oh, God. I’m not ready to talk about a baby shower.” I’ll talk about babies all day long. I work in the hospital, and then someone will say something, and I’m like, “I can’t have kids.”

I feel there are certain times when I didn’t process things. There are certain things that I’m happy for other people, certain things where I am not happy for other people.

Your tips on how to minimize “scanxiety”

I’m all about making plans as far as keeping your anxieties down for certain things.

I make sure that I see my doctor within 24 hours of my scan. That way, I don’t worry about it for weeks on end. I also make sure that every time that I do have a scan, I have a plan for that night after I get my results with somebody.

Whether it’s the same person or not, I need to have dinner planned that Thursday night. That way, if I get bad news, I have someone to be there with me. If I get good news, we can celebrate.

Cancer is probably 98% of my day. It’s not 110% anymore, but it’s still something that’s part of my day.

It’s more so now feel that it’s part of my day trying to be supportive to others and to show others– Just even mental health-wise, you have to just move forward and be okay with where you’re at. If you need help, you need help. If you don’t need help, just let that day go kind of thing.

How have you processed the loss of fertility from cancer?

I honestly can say that I have not processed and dealt with it. I don’t think that I ever will. I would rather my significant other have a biological child, so my goal would be a surrogate.

Obviously, my goal was my own child, so that’s not going to happen. It is one of those things that in my head I have that as my plan. My plan is my husband will get a surrogate. If that doesn’t happen, we would work on adoption. I do want to be a mom.

In the beginning, this was a topic that would not be talked about without me sobbing my eyes out. I would not be able to have this conversation. Not that I’m better with it. I can’t control that, especially with my boyfriend. I had to have the conversation early on that I can’t have kids.

He’s younger than me. To have to tell him, “You can’t have kids with me. This isn’t going to work,” was a very big step. Once I started getting to know him, I told him, “We need to have a talk. I need to tell you some things.”

We sat down, and we talked about it. I explained it to him. I had given an out. I said, “You can stop dating me. I don’t have a choice in the matter here. This is my reality. You have a choice.” Thankfully, he did not leave me for that.

Say 10 years from now, I’m doing very well; everything’s still stable. I’m still no evidence of disease. We have a surrogate, and we have a baby. I feel that it’s one of those things that at that time, maybe I’ll have a different perspective on things, like, “Okay, it doesn’t matter how you got that baby, how that baby became yours. You’re his or her mother.” That’s what the ultimate goal is.

There are people who try with fertility treatments for years on end and never get pregnant. That’s how I approach it with my boyfriend as well. I’m not fertile from the get-go. We don’t have to do thousands of dollars of IVF treatments to try to have a baby. We just can’t.

That helped me a little bit to be like, “Okay, I don’t have a choice. This is my reality.” Obviously, in the beginning I was told the fertility versus survival situation.

They basically told me, ‘You can keep your other ovary, but you will not probably be alive long enough to raise that child.’

At the time, I felt like saying, ‘Oh my God, that’s mean,’ but I think that I needed to hear it that firm to be like, ‘Okay, you’re making the right choices.’

How has the transition been to survivorship?

It’s hard because COVID happened. It was not until about three months after chemo ended when I actually ended up being able to be like, “Okay, I’m getting more of control back.”

Certain things came back. I started to see how I would feel that day, be okay with that, and stop fighting a lot of it.

I met my amazing boyfriend about three months after I finished chemo. As much as he tries to understand it, he doesn’t understand it to a certain extent, but he is very much super, super supportive. Bless him for getting all of this dumped on him and then being in for it.

He has helped significantly with the transition. I do feel that that’s something that I would not be where I’m at had I not met him at the time that I did, because there were many times that he didn’t know the “cancer me” as much.

He knows me now, so he doesn’t know the really sick me. We’re able to do things that don’t relate to cancer, and I think that that’s a huge thing with moving forward and past the chemo time frame.

Do things that are not chemo or cancer related. If you like to work out, do that. If you like to go for hikes, do that. It’s more that it helps you remember cancer’s not you.

Inspired by Sara's story?

Share your story, too!

Ovarian Cancer, High Grade Serous Stories

Randalynn V., High-Grade, Stage 1C

Cancer details:Account for up to 70% of cases

1st Symptoms:Pulling sensation when emptying bladder; abdominal pain

Treatment:Chemotherapy (Carboplatin & Paclitaxel) & surgery

...

Shirley P., High-Grade Serous Carcinoma, Stage 3C, BRCA1+

Cancer details:Account for up to 70% of cases

1st Symptoms:Pulling sensation when emptying bladder; abdominal pain

Treatment: Chemotherapy (Carboplatin & Taxol), de-bulking surgery & PARP inhibitors

...

Suzann B., High-Grade Serous Carcinoma, Stage 3C, BRCA1+

Cancer details:Account for up to 70% of cases

1st Symptoms:Inability to urinate

Treatment: Chemotherapy, de-bulking surgery & total hysterectomy

...

Susan R., High-Grade, Metastatic

Cancer details:Account for up to 70% of cases

1st Symptoms:Pulling sensation when emptying bladder; abdominal pain

Treatment: Chemotherapy (Carboplatin & Paclitaxel) & surgery

...

Sara I., Clear-Cell, Stage 3A

Cancer details: Account for ~ 5-10% of ovarian cancer cases

1st Symptoms: Random sharp pains, unrelated scan showed ovarian cyst

Treatment: Debulking surgery, chemotherapy (carboplatin & paclitaxel/Taxol), clinical trial of PARP inhibitors

...