Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma Highlights from ASH 2022

The Role of Bispecifics in the Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma

Patient advocate Jack Aiello is a 28-year survivor of multiple myeloma. When he was diagnosed, he was told he would only have two to three years to live and only two treatment options were available.

Jack underwent two transplants and then went onto a clinical trial for thalidomide but nothing worked until a third transplant.

In this conversation, he speaks with Dr. Ajai Chari, the Director of Clinical Research at the Multiple Myeloma Program at Mount Sinai in New York and Dr. Sandy Wong, a blood disease specialist at University of California, San Francisco, with a special interest in multiple myeloma.

They discuss game-changing treatments for relapsed/refractory patients, bispecific antibodies, treatment side effects, and emerging clinical trials.

Thank you to Janssen Oncology & AbbVie for their support of our patient education program! The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content.

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

- Introduction

- Bispecific antibodies

- Treatment for relapsed/refractory patients

- How is talquetamab is different from other bispecifics?

- What makes alnuctamab different from other bispecifics?

- What are common side effects for bispecifics?

- Lowering cytokine release syndrome with treatments

- Managing side effects for bispecifics

- Next steps for research

- Final takeaways

- Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma Patient Stories

For today’s newly diagnosed patient, you can be more optimistic about your diagnosis than [at] any time in history. We don’t have a cure [but] we have treatments available to manage this disease.

Jack Aiello

Introduction

Jack Aiello: I’m a 28-year survivor of multiple myeloma. When I was diagnosed in 1995, the doctor told me I had two to three years to live and [that] there were only two treatment options available. I remember going home to my wife, [telling] her the little bit I understood about this disease, and, suffice it to say, we shared a good cry.

I had kids who were 16, 14, and 10 years old at the time. I knew I was going to have to go to the hospital so I just told them that there was something wrong with my blood and I was going to have to have it treated. But I wondered, would I be seeing the kids graduate from high school? Who was going to teach my son to hit a curveball in Little League? Who was going to pay for them [to go] to college? It was a difficult time.

Since then, we’ve had 13 or 14 new drugs approved by the FDA, more combinations of these drugs, and even more are in clinical trials today.

I really believe that for today’s newly diagnosed patient, you can be more optimistic about your diagnosis than [at] any time in history. We don’t have a cure [but] we have treatments available to manage this disease.

For relapse/refractory patients, you’ll hear some great results from the recent ASH meeting. Many abstract presentations were on the topic of drugs and a category of drugs called bispecific antibodies.

To help us understand more are Drs. Ajai Chari and Dr. Sandy Wong.

Dr. Ajai Chari is the Director of Clinical Research at the Multiple Myeloma Program at Mount Sinai in New York.

Dr. Sandy Wong is a blood disease specialist at [the] University of California San Francisco, with a special interest in multiple myeloma.

Let’s kick off the conversation with what was the big buzz this year: bispecific antibodies. We’ve heard of monoclonal antibodies like daratumumab. Most recently, the FDA approved a bispecific antibody called teclistamab or Tecvayli. What exactly is a bispecific?

Bispecific antibodies

Dr. Ajai Chari: It’s a really exciting time. I’ll start with one of my favorite stories about the development of immunologic treatments in all humans. In [the] 1980s, the Nobel Prize was actually given for creating a standard antibody that was taken by fusing a myeloma cell with a spleen cell.

Every human antibody that we use — whether it’s for COVID, autoimmune diseases, [or] cancers — owes its legacy to myeloma. The first naked antibody, which is this Y-shaped structure, was not approved [for] myeloma until about 30 years after that Nobel Prize was given even though antibodies were helping everybody else.

The first naked antibodies were daratumumab and elotuzumab. The ends of the Y-shape bind to one target and typically that’s the myeloma cell or whatever cancer cell.

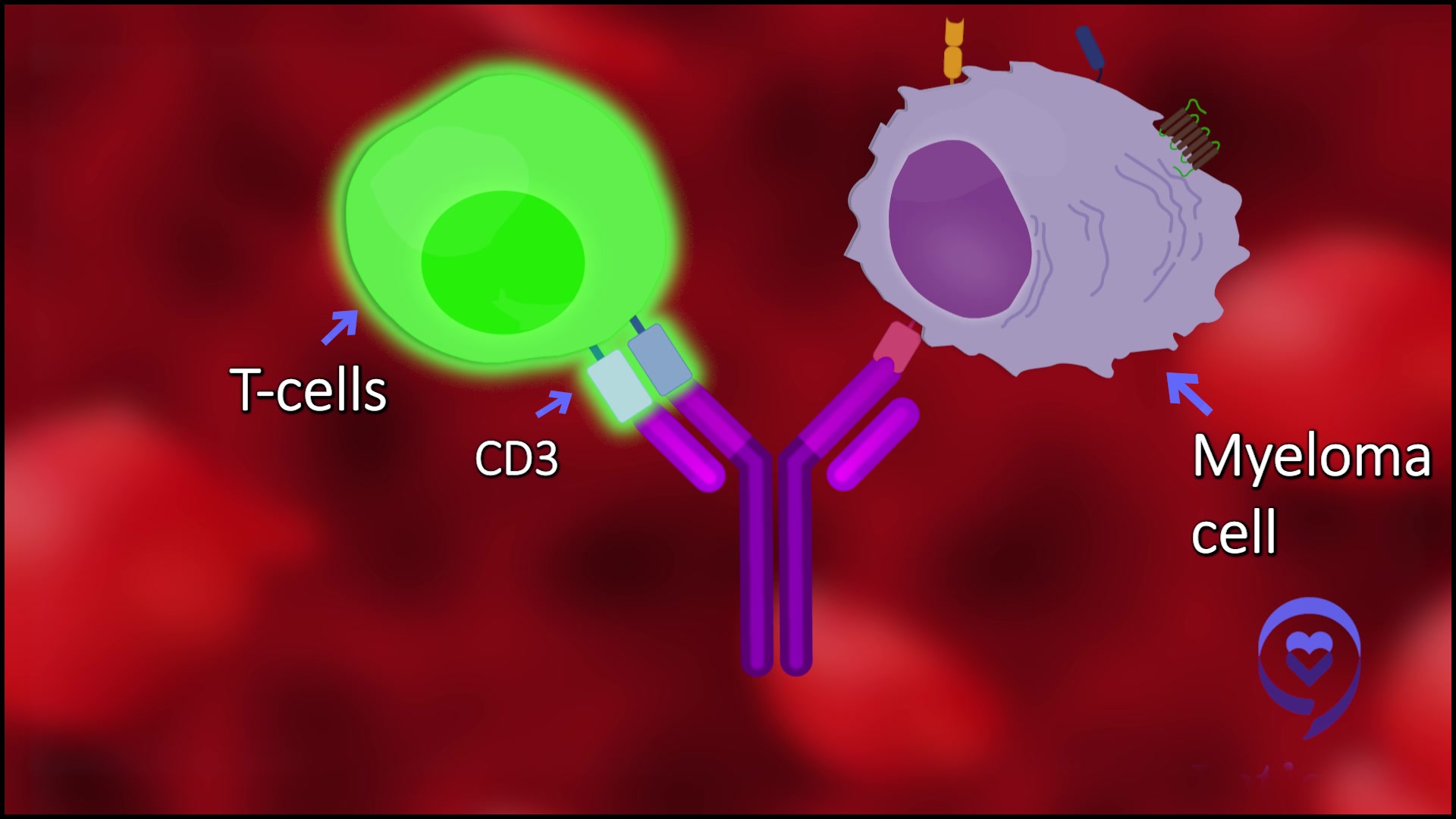

It’s either a handcuff or double-sided tape. Basically, what it does is it takes one side of the Y, binds to a T-cell through a target known as CD3, and the other side can bind to a myeloma cell. You can change that up based on the protein.

The one that’s commercially available now that’s called teclistamab binds CD3 and the T-cells to BCMA or B-cell maturation antigen.

It’s remarkable how well these agents are working.

Dr. Ajai Chari

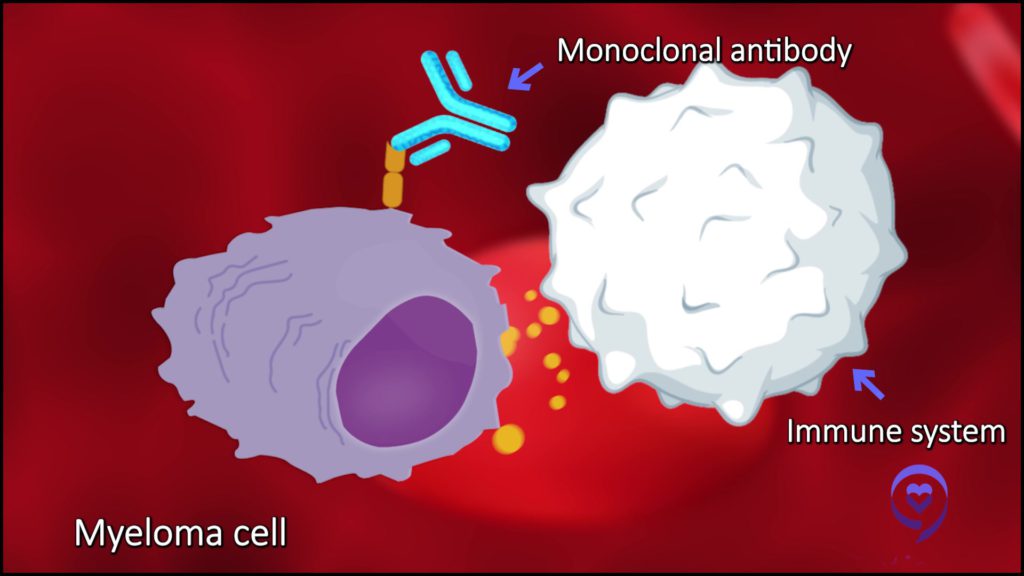

Jack: So the difference between that and a monoclonal antibody is the monoclonal antibody doesn’t have that second arm connecting to the T cell, is that correct?

Dr. Sandy Wong: That’s correct. Monoclonal antibodies activate the immune system in a different way.

For example, drugs like daratumumab or isatuximab activate the immune system [in] several ways. One is they act almost like Post-It Notes, if you will, where they flag cells [that] are not supposed to be there, i.e. the myeloma cells, and that leaves the immune system to know, “Hey, this is not supposed to be there. Let’s get rid of this myeloma cell.” That’s how a monoclonal antibody works.

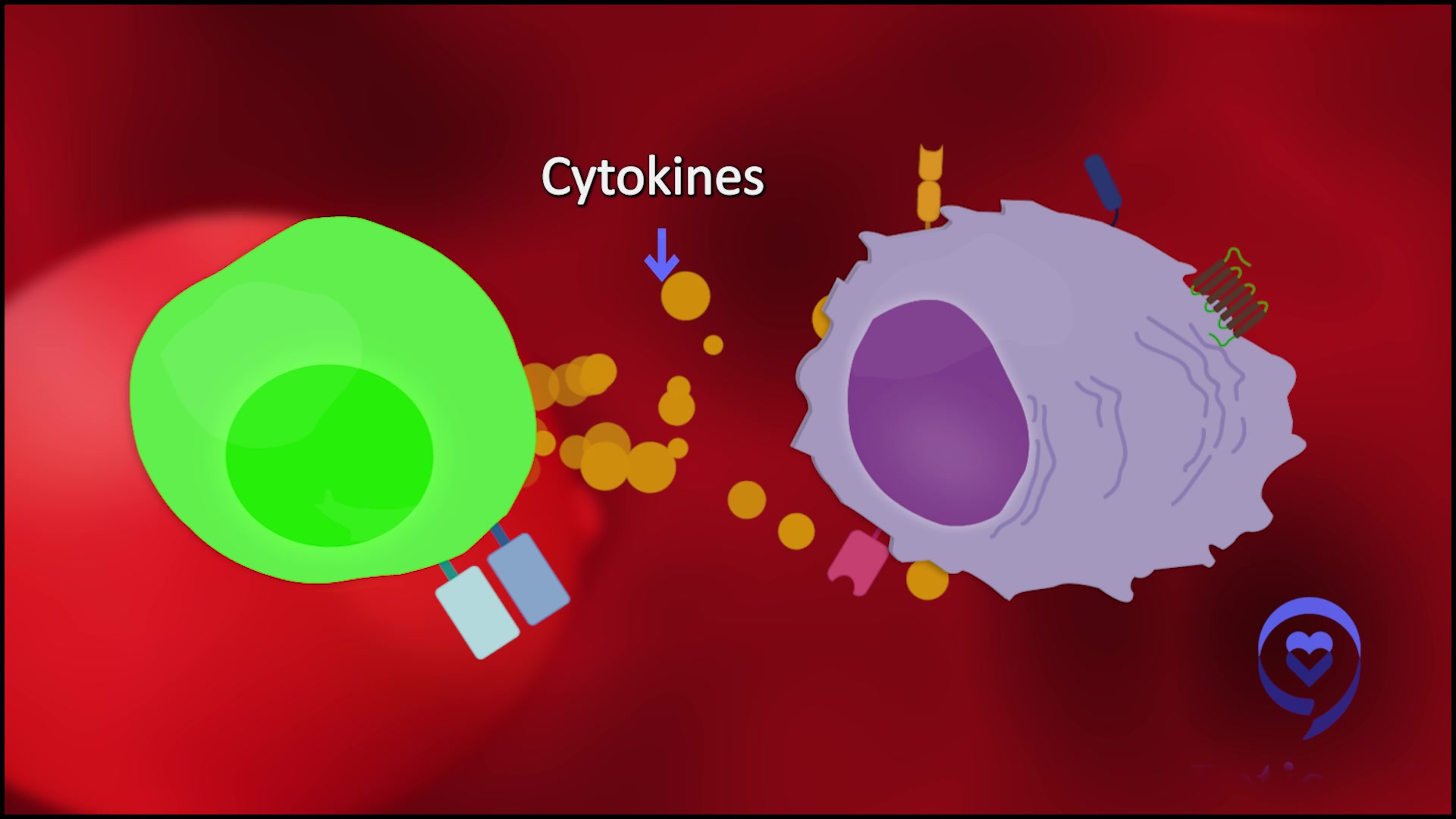

Bispecific T-cell engagers physically attach to T cells and bring the T cells in physical proximity with the myeloma cells. The T cells get rid of myeloma cells that [are] not supposed to be there so they secrete their toxins, etc., and get rid of the myeloma cells. They work very differently.

Dr. Chari: It’s remarkable how well these agents are working. Basically, it’s an off-the-shelf product so that’s important.

A lot of people may have heard about CAR Ts that also target BCMA, but the difference is this is ready to go. It doesn’t have to be manufactured for each patient.

You don’t need to go through the T cell collection, manufacturing, and waiting. This is an off-the-shelf product. That’s the same for every patient with myeloma.

What the drugs do is basically traffic the T cells in our bodies to whatever you’re trying to bring them to. In this case, the T cells in a patient are preexisting or trafficked to wherever the myeloma is, and when the T-cells are brought right up against the cancer, they recognize the cancer.

They release certain chemicals or cytokines that poke holes in the cancer cell and that lead to cell death. I say it’s like bringing your army straight to the enemy, as opposed to hoping and praying that they find the right place to go.

It’s a mind-changing, game-changing era that we’re in with this immunotherapy treatment.

Dr. Chari

Treatment for relapsed/refractory patients

Jack: The teclistamab that was just approved and the other bispecifics, just to let the [readers] know, are so far for relapsed/refractory patients. Those [are] patients who have gone through several lines of previous treatments before getting to these bispecifics. Is that right?

Dr. Chari: Yeah, that’s exactly right. Just to put this whole space into context, about five [or] six years ago, the way drugs get approved is that they’re first tested in heavily treated patients — as you mentioned, relapsed/refractory myeloma.

The benchmark to get a new drug approved was about [a] 20-30% response rate, lasting about three to four months. Those numbers sound modest, but we have to keep in mind those are in patients who had exhausted all available therapies.

When I started in myeloma 17 years ago, thalidomide was just coming on the scene. At that point, [to treat] relapsed/refractory, you had thalidomide and maybe a transplant. Now, typically, we’re talking about the big five drugs:

- lenalidomide (Revlimid)

- pomalidomide (Pomalyst)

- bortezomib (Velcade)

- carfilzomib (Kyprolis)

- CD38 antibodies, such as daratumumab or isatuximab

That is a very different patient than somebody who just had had thalidomide. As we keep approving drugs, this unmet need, which is patients who have exhausted their currently available therapies, keeps changing.

In spite of that, what’s remarkable about the entire T cell redirection, whether it’s bispecific or CAR T, is we’re saying 70-100% [response rate] is the new 20-30%. That’s how many patients are responding to these drugs. Even though these are much, much sicker patients and have had more treatments [and] more drugs, we’re getting better responses.

That’s what’s really exciting. I literally have patients [with] whom we had discussed hospice a few years ago and now they’re in their deepest, longest remission they’ve had in years. It’s a mind-changing, game-changing era that we’re in with this immunotherapy treatment.

How is talquetamab is different from other bispecifics?

Jack: For one who’s been watching new treatments being developed and now seeing [a] 60% or 70% response rate, it’s pretty incredible.

Dr. Chari, you presented a different bispecific called talquetamab, also from Janssen, the same manufacturer of teclistamab. Can you share the results of this trial and what might make talquetamab different from other bispecifics?

Dr. Chari: First of all, this work takes [a] tremendous team, starting with the patients and their caregivers and then the entire study team, Janssen, the pharmaceutical, the FDA, and other regulatory agencies.

With the phase 1 portion of the study, we’re looking to just find the safety and what’s the right dose and schedule. The phase 1 study just got published in [the] New England Journal so that was very exciting. It was also a large phase 1 study with over 200 patients.

Efficacy and safety (how well it works in the safety profile) were then validated in this phase 2 study and that’s what we presented at ASH [2022]. The phase 2 study had 3 major cohorts of patients:

- One got a dose of what we call 0.4 mg per kg subcutaneously every week

- A second cohort got 0.8 mg per kg every two weeks

- The third cohort could have gotten either one of those doses, but [in] a very important subgroup of patients who already had prior T cell redirection therapy, meaning patients who had had other CAR Ts and bispecifics

Even though these are 60-100% response rates, we’re still seeing relapses so you still need new agents. The goal of this study was to really look at these three subgroups. I would start with who these patients were. These were patients with heavily-treated disease.

About 60% were high-risk in some way, which is a very high number. That could be defined either by what we call high-risk genetics, so cytogenetics and FISH; high risk because they had myeloma coming out of the marrow, what we call extramedullary disease; or high risk because they had so-called ISS stage 3 disease at the time of study entry.

In this population, with the typical five to six lines of therapy over six to seven years where almost 95% of patients were refractory to daratumumab, 75% were what we call triple-class refractory (proteasome inhibitor, IMiD, and CD38) and 95% of patients were progressing on their last therapy.

In this heavily, heavily treated group, as a single agent drug, we saw [a] 73-74% response rate in both of those schedules that we mentioned. That response rate was maintained in high-risk patients, ISS 3 patients, and patients regardless of lines of therapy, regardless of the number of drugs they were refractory [to].

One group who had [a] slightly lower response rate was those with extramedullary disease and even those had a 50% response rate, which I think is outstanding. I think safety is also equally important and distinguishes this from some of the other drugs.

What makes alnuctamab different from other bispecifics?

Jack: Dr. Wong, you presented on a bispecific called alnuctamab from Bristol Myers Squibb. Can you share the results of this trial and what might make alnuctamab different from other bispecifics?

Dr. Wong: We presented both the updated follow-up on the intravenous alnuctamab cohort as well as the subcutaneous alnuctamab cohort. The intravenous cohort was actually presented initially in ASH 2019 so there’s been quite some time that’s elapsed.

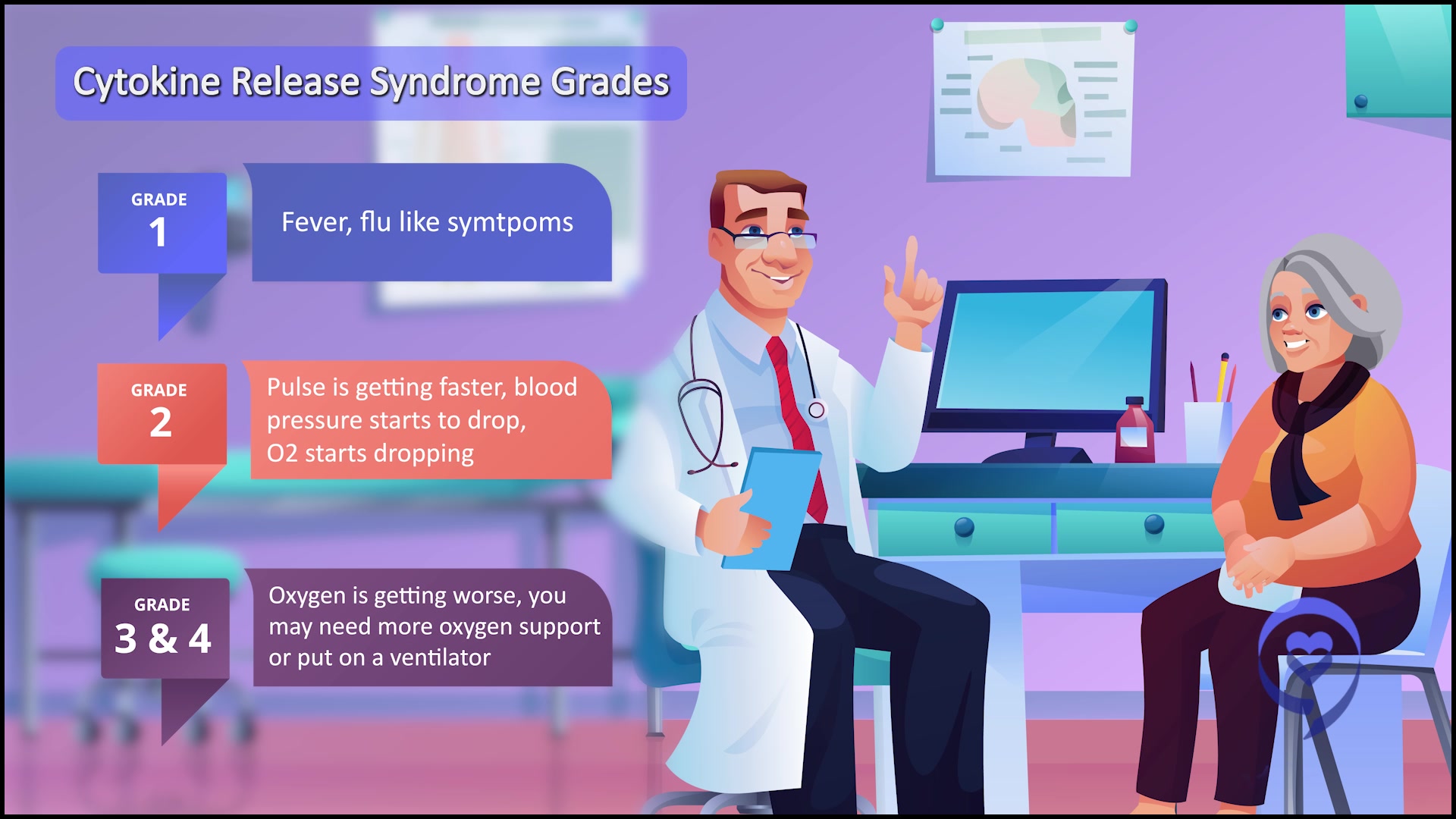

Basically, the take-home message with the IV alnuctamab was that even though the response rates initially looked exciting, when we got to target doses of 10 mg, there was a lot of high-grade cytokine release syndrome. People got really sick from CRS and one person actually died from it so it was not really optimal in terms of the side effects. Obviously, we don’t want people to get sick from these treatments.

Patients that were on the intravenous alnuctamab responded for a really long time so we’re really, really excited about that. However, we had to pivot to the subcutaneous alnuctamab because of those safety concerns. With the subcutaneous alnuctamab, the overall response rate was at 65%, which is very much in line with other T-cell engagers.

In terms of safety, all the CRS events were very low-grade. They were short-lived. They’re what we call grades 1 to 2 and, in terms of safety profile, it was a lot more manageable compared to intravenous alnuctamab.

That was what was really exciting about our presentation. Not only is subcutaneous obviously more convenient for patients, but the CRS events were much easier to handle and the overall response rate was 65%.

How does this stand out from the other T cell engagers? Several things. This is not the only subcutaneous BCMA-directed T cell engager, but there are some that are intravenous. For example, ABBV-383 is intravenous. So this is great that this is subcutaneous.

It’s hard to compare apples to oranges because all these different BCMA-directed T cell engagers have different follow-up time frames. For this one, the follow-up was very, very short. The median [was] only around four months.

In terms of infectious events, in terms of opportunistic infections, we really haven’t seen much of that for this particular drug so maybe that eventually will pan out longer follow-up studies but unclear because follow-up is pretty short.

What is really exciting is that the MRD negativity was 80% despite these patients [not being] followed for that long. That is actually really exciting. We don’t have a signal for these high-grade infections or opportunistic infections though. Again, follow-up is pretty short with this drug.

What are common side effects for bispecifics?

Jack: Speaking of infections, what are the common side effects we’re seeing with bispecifics altogether? I understand some research is unearthing data about how myeloma patients on certain drugs do with COVID and the vaccine.

Dr. Chari: I’ll start with what’s the most severe toxicity and then we’ll go to what’s common because I think they’re different and they’re both equally important to address. From a patient perspective, if it’s severe but rare, you may not be as concerned, but if it’s common and frequent, that’s different.

The most severe side effect is low blood counts. We see that in about a third of patients with this drug. Typically, it happens in the first few cycles.

My personal hypothesis, I think what’s happening is when the army is going to the marrow where a lot of myeloma lives, you kill the myeloma but you may temporarily also affect the rest of the marrow. Then once the myeloma clears, you see that [improvement].

Jack: Patients may hear that called cytopenia. Is that correct?

Dr. Chari: Correct. That’s exactly right. It could be the white cells, the red cells, or the platelets. Those are important. This is already a little bit less than some of the other drugs, which can have as high as 60%. This is about half of that.

The second huge thing, which you alluded to and it’s very important, is the infection. I can tell you, being in New York City [during] the pandemic, this was really a difficult situation. We had patients on experimental therapies and we were facing these life-threatening COVID decisions every day. We didn’t know what to do with this setting.

I think the infection profile of talquetamab is very unique. I’ll give you three ways why I think it differs from some of the other products.

First, the rate of severe infections was about 10-15%. We want it to be zero, but to put that into context, some of the other drugs are 45%.

We’re not just talking [about] minor infections, which can be seen with any myeloma patient because of the nature of the disease. [These are] severe, life-threatening infections, what we call grade 3-4. That was relatively modest.

Second, the COVID signal is very different with this agent. Talquetamab as well as a lot of the other bispecifics are all accruing during the era of COVID. Yet in the phase 1 study that was published in [the] New England Journal with about 250 patients, there were zero COVID-related deaths.

In this study, there were two COVID-related deaths despite 10% of the patients having COVID. That’s a unique signal. In fact, in our laboratory at Mount Sinai, when we’ve tested people getting talquetamab [and] their response to the COVID vaccine, they do very well. They’re able to generate antibodies, which we don’t see with some of the other bispecifics because of the nature, I believe, of the target.

The third and final difference between this drug and some of the other bispecifics is the need for infection-prevention treatments. Is there anything we can do to reduce infection? There is IVIG, which is intravenous immunoglobulin, that’s an intravenous infusion given once a month to boost IgG levels. Here, only about 10% of patients needed IVIG.

All of those features of this drug are very unique. Some of the other products are having as high [a] rate [as] 40% of patients needing IVIG. I think this bodes well because these are probably the two most important features, which [are] cytopenia, blood count, and infections in terms of how these drugs are used in the future.

The ability to combine drugs depends on each agent’s side effect profile. Because infections and blood count issues are quite common, that can make some of these bispecifics difficult to combine. I think, in contrast, that bodes well for talquetamab.

There are some issues with talquetamab that are common but typically low-grade. One you’ve alluded to is cytokine release.

I would say as a class, all the bispecifics have cytokine release syndrome on the order of 70% or so, typically low-grade. In contrast, some of the CAR Ts have a little bit higher, more severe cytokine release.

What is cytokine release? It’s when the army recognizes the cancer. The T cells release their chemicals and those chemicals can cause symptoms such as fever, low blood pressure, low oxygen, confusion, lethargy, seizures, and even death, in rare cases. With bispecifics, it’s generally very low-grade. Most of the patients are getting a fever.

Everybody eventually would love to be able to use these drugs [in] an outpatient setting… If we’re able to do this safely as an outpatient, that would be really a big game changer for patients and their quality of [life].

Dr. Sandy Wong

Lowering cytokine release syndrome with treatments

Jack: There’s a big focus on lowering cytokine release syndrome with treatments like bispecifics. In particular, I saw one trial which looked at trying to reduce CRS by giving tocilizumab ahead of time. I’ve seen things like step-up dosing to reduce side effects. I know doctors have asked for possible pre-treatments for reducing infections. Can you share more about this?

Dr. Wong: Everybody eventually would love to be able to use these drugs [in] an outpatient setting. Nobody wants to be admitted to the hospital for a week just to get started on these drugs. If we’re able to do this safely as an outpatient, that would be really a big game changer for patients and their quality of [life].

Dr. Chari: We have to keep in mind one of the very things that’s going to make bispecifics different than CAR T.

CAR Ts are done at transplant centers and specialized large academic centers. These are off-the-shelf products that we hope eventually can get to the community because we recognize that most myeloma patients are not being treated in the global setting and academic centers. They’re being treated by community doctors.

If we want to get these drugs out to the community, we have to make them as safe as possible. How do we reduce that 70% cytokine release? One is by giving tocilizumab. In one of the studies with a bispecific known as cevostamab, [the] rate of cytokine release dropped from 70-80% to about 30%. That’s very encouraging.

The other way to do that, which you mentioned, is don’t throw the whole army at the disease at once. Gradually increase the doses so that if there is some chemical release, it’s not all at once. That creates a lot of drama. You start with a low dose and you gradually work your way up.

Both strategies are being done. With talquetamab, we did do preventative tocilizumab, which is the anti-IL-6 antibody, which blocks the fever. We were allowed to give it when patients had cytokine release, but we didn’t give it preventatively, which is what was presented at ASH [2022] in that one study.

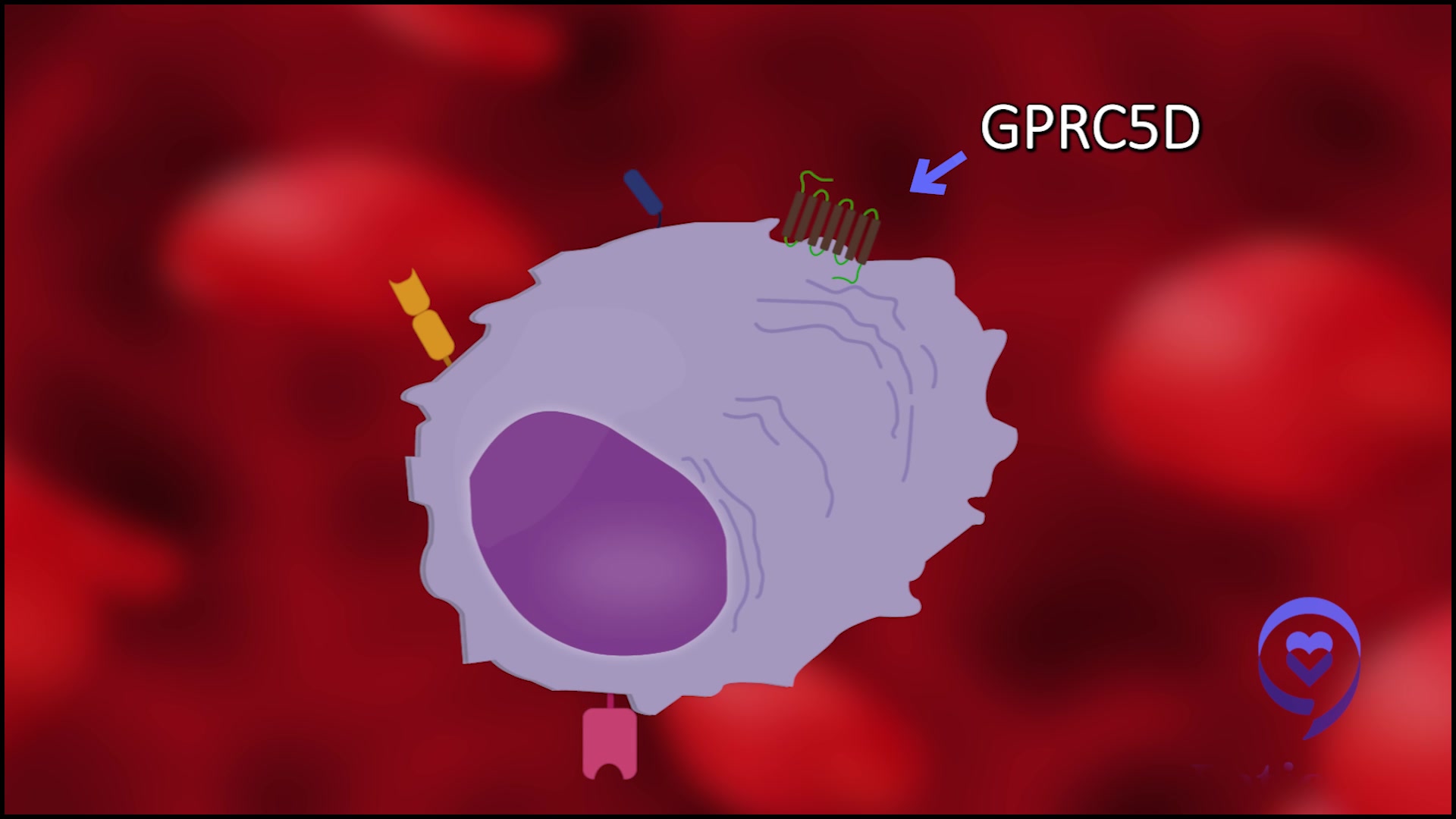

The other side effects [of] this drug are three things. One could ask, “Why is this one different than other drugs in terms of why potentially the infection was better? Why were the blood count issues perhaps not as bad?” We think it has to do with the target.

The target is GPRC5D, which is basically a protein that is expressed on myeloma cells primarily. We think [it’s expressed] less so [in] normal plasma cells and even less so in the normal hematopoietic compartment, which is the precursor cells that give rise to our blood counts.

Perhaps the specificity of this protein is what underlies the favorable blood count and cytopenia issues, as well as the infection profile. There are a few tissues that do express GPRC5D and, fortunately, it’s not the major organs. We didn’t see [the] heart, lung, liver, [and] kidney. Those organs were not affected.

The main thing we did see is GPRCs expressed on heavily keratinized tissue. Keratin [is] in the skin, nails, hair, etc. We didn’t see a lot of hair loss, but we did see some rashes in the early part of the treatment, which [is] typically managed with either oral or topical steroids.

We did see some nail changes and taste changes. We saw dryness, difficulty swallowing, [and] change of taste. That, I think, is the most difficult to manage. We’ve tried artificial saliva and other things.

In spite of everything, the one signal that you can look at to see the tolerability of a drug is how many people came off for non-progression. This was 5%, which means that we were able to manage the side effects to keep people on the drug. I still think we need to do better.

We have to keep in mind that the side effect profile that a heavily treated population might accept is going to be different than the side effect profile of maybe somebody who’s only had one line of therapy.

The good news is that we do think these side effects are responsive to modulating the dose and intensity, so either dropping the dose or skipping a dose, giving it less frequently. Those seem to help. I think that’s why the rate of discontinuation was relatively low.

Again, a huge shout-out to the nurses because they’re really on the front lines and helping patients deal with these side effects. I never take my entire outstanding, talented nursing colleagues for granted. They’re really doing an amazing job. Those are basically, I think, the main side effects to cover with talquetamab as well as most bispecifics, I would say.

We have to keep in mind that the side effect profile that a heavily treated population might accept is going to be different than the side effect profile of maybe somebody who’s only had one line of therapy.

Dr. Chari

Managing side effects for bispecifics

Jack: Let’s summarize the side effect profiles for these bispecifics. I would stay on bispecifics typically until they stop working. I take them every two or three weeks, depending on how they’re dosed. Do these side effects change? Are they worse at the beginning? Whatever side effect I get at the beginning, [does it] continue as I’m taking the drug?

Dr. Chari: There [are] three major bispecific targets that are being explored. We’ve talked about GPRC5D with talquetamab. There’s actually a second company also pursuing that. That was also presented at ASH [2022] from Roche, targeting GPRC5D.

The BCMA is a very busy space. I think it’s like the statins of myeloma, like Crestor [and] Lipitor. It’s great for patients because more competition means more choice [and a] better cost profile. I think it’s great for the market.

I would say the BCMAs seem to keep having a rate of infection that we don’t see a plateau in. That’s what’s concerning to a lot of us. How do we find the right dose, schedule, and duration?

It’s one thing to have an infection in somebody whose myeloma is uncontrolled because that we’ve seen before. Myeloma patients whose myeloma is uncontrolled will get infections because that’s part of the cancer.

What can be sometimes difficult to tease apart in these single-arm studies is you can’t isolate what’s coming from the patients (like if the patient is a very sick patient), what’s coming from the disease of the myeloma itself, and what’s coming from the treatment because you don’t have a control arm in which to compare it to.

One of the things, as your question astutely asked, is there any change? With the infections, we’re not seeing that level off with the BCMA. With talquetamab, we’re not seeing it as much.

I would say with the cevostamab, it’s probably somewhere in between. That’s targeting another protein called FcRH5. I would say [with] infections, we haven’t found the right magic sauce yet. Perhaps IVIG.

One other interesting paper that I think speaks to this topic is Genentech/Roche, the same company that did the prophylactic or preventative toci (tocilizumab) also happens to have the only bispecific that is a fixed duration. They don’t treat the progression. They treat for about a year.

What we saw is there’s a small number, but about 17 patients that had come off the therapy and were in longer follow-up on that study. What we know so far is of the patients that had a deep remission, they’ve been doing pretty well off therapy. Again, [that’s] amazing for patients to have a treatment-free interval.

With talquetamab, we’re not seeing that relentless increase in infection — and to the opposite, the side effects [with] skin, nails, and taste actually seem to get better with time. There may not be as much of a need to do the fixed duration there. Maybe it’s once-a-month dosing or something.

We’re pursuing all of these different strategies, but I would say that we’ve got to look at everything. We’ve got to look at the dose, the frequency, [and] the duration of treatment and figure [it] out for a given patient, based on a given target and on their response.

That cevostamab data, which [was] discontinued for those patients that were not in a complete response, did have [an] earlier relapse.

I think you can’t have a blanket statement. You just got to look at each patient as an individual. It’s nice to have these options that are giving such outstanding responses.

Bispecifics are here. It’s a dawn of a new era… We have multiple drugs against multiple targets that are showing impressive response rates.

Dr. Wong

Next steps for research

Jack: Thank you so much. I’ve learned a lot about bispecifics. I can also tell there’s still a lot of work to do to understand the dosing, to understand if there will be prophylactics that go along with them to minimize those side effects, to see if fixed duration or use till progression will be the right treatment, or just to reduce the dosing going forward.

I still go back to what you said earlier that we’re seeing response rates so high for just this drug, not even combined with something else, and for patients that have already gone through lots of prior treatment lines. It’s certainly an exciting field.

Dr. Chari: Not only are we seeing these responses, [but] the median time to response is one month and the median time to best response is two months. I mentioned those points because it gives us, as physicians, a lot more comfort in backing off on the dose and schedule.

You’re seeing the response early and it’s deep. If somebody has side effects, you’re not as worried about backing off. That’s what’s really nice about these drugs. Even if somebody does have side effects, it’s very gratifying to them to have this myeloma that was shooting off and suddenly it’s completely flattened out. That’s why I think the side effect profile we’ve got to do more work on.

What are the next steps? All the phase 1 and phase 2 single-arm studies have confirmatory randomized studies where the drug’s being combined with different backbone agents.

Also, because of the unique side effect profile, talquetamab in particular is also being combined with all those standard myeloma drugs in single-arm studies as well as with the other bispecific, which is really cool. Completely chemo-free teclistamab with talquetamab is being studied.

Lastly, we’re trying to also improve the T cell function because we think one of the reasons the drugs may peter out is because of T cell health. There [are] approaches using things like checkpoint inhibitors, which boost your T-cell function, in combination with these agents.

Bispecifics are going to be a fabulous treatment option for myeloma patients… I’m excited to see what comes next in myeloma.

Jack

Final takeaways

Jack: Doctors, as we wrap up this discussion on the latest in myeloma, specifically bispecifics, what are your thoughts on where we are in myeloma treatment and research? What’s your message to myeloma patients and families in 2023?

Dr. Wong: Bispecifics are here. It’s a dawn of a new era because finally, we have [an] off-the-shelf drug, which means that you can just take it right off the shelf and just give it to a patient. And for an off-the-shelf drug to have a response rate of 60 to 70%? That is absolutely amazing.

Previous to this, dara (daratumumab) was our darling drug. We use it so common nowadays in the front-line setting and the relapse setting. When dara was FDA-approved, the single-agent response rate in patients who are relapsed/refractory was only around 30%. Right now, we’re hitting 60 to 70% so this is extraordinary.

And it’s not just one drug. We have multiple drugs against multiple targets that are showing impressive response rates. I think really good news this ASH. I’m really excited to see all that amazing data being presented.

Dr. Chari: I think it’s a really exciting future. We’re just in the beginning and, of course, in less heavily treated patients, it’s also a big area of investigation in addition to combination. Stay tuned for all of those exciting new studies, hopefully soon.

Jack: Bispecifics are going to be a fabulous treatment option for myeloma patients. Thank you so much, Dr. Chari and Dr. Wong, for your presentations, [for] helping us better understand bispecifics, and [for] being part of this conversation.

I hope you took away something helpful and hopeful from this conversation. I’m excited to see what comes next in myeloma.

Special thanks again to Janssen Oncology & AbbVie for their support of our independent patient education content. The Patient Story retains full editorial control.

Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma Patient Stories

Theresa T.

Diagnosis: Multiple myeloma, relapsed/refractory

Subtype: IgG kappa Light Chain

Initial Symptom: Extreme pain in right hip

Treatment: Chemotherapy, CAR T-cell therapy, stem cell transplant, radiation

Laura E.

Symptom: Increasing back pain

Treatments: Chemotherapy, stem cell transplant, bispecific antibodies

Donna K.

Diagnosis: Multiple myeloma, refractory

1st Symptoms: None, found by blood tests

Treatment: Total Therapy Four, carfilzomib + pomalidomide, daratumumab + lenalidomide, CAR T, selinexor-carfilzomib

Connie H.

Diagnosis: Multiple myeloma, relapsed refractory

1st Symptoms: Chronic bone pain

Treatment: IV Chemotherapy, CAR T cell therapy

Elise D.

Diagnosis: Multiple myeloma, refractory

1st Symptoms: Lower back pain, fractured sacrum

Treatment: CyBorD, Clinical trial of Xpovio (selinexor)+ Kyprolis (carfilzomib) + dexamethasone

Beth A.

Diagnosis: Multiple myeloma, relapsed/refractory

Subtype: Non-secretory (1-5% of myelomas)

1st Symptoms: Extreme pain between shoulder blades, sternum, head, burning sensation

1st Line Treatment: VAD chemo, radiation, stem cell transplant

RR Treatment: 8 chemo regimens, successful combo→selinexor+bortezomib+dexamethasone

Scott C.

Diagnosis: Multiple myeloma, relapsed/refractorySubtype: IgG lambda (majorityof myelomas)

1st Symptoms: Pain in hips and ribs, night sweats, weight loss, nausea

Treatment: Clinical trial, chemo, kyphoplasty, stem cell transplant