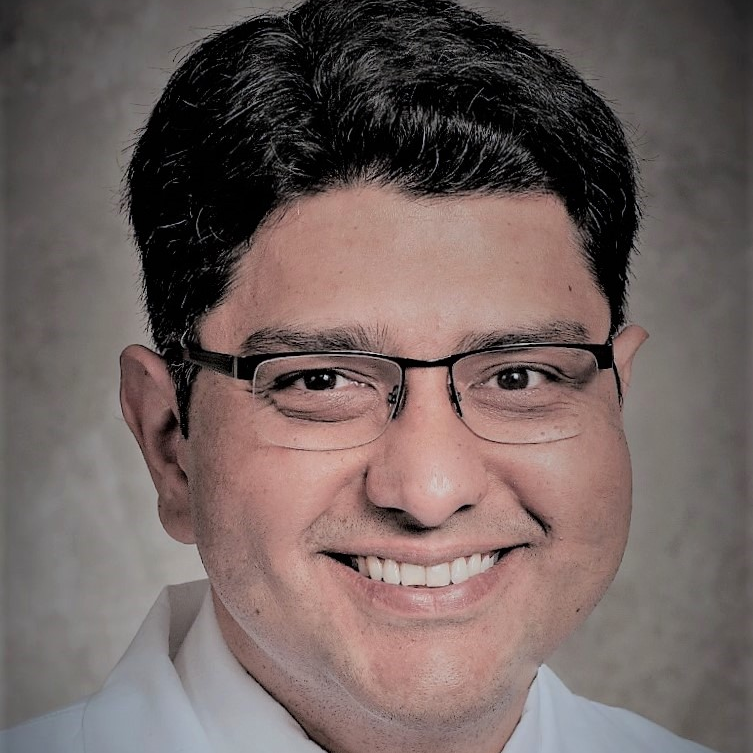

Nina Shah, MD

The Latest in Multiple Myeloma Treatment & Clinical Trials (2021)

Nina Shah, MD brings hope to multiple myeloma patients with news of standard of care trends and updates.

She lends here her expertise in managing multiple myeloma and experience improving patients’ quality of life.

Read Dr. Shah’s insights on the treatment decision-making process, patient and provider communication, and more.

Thank you, Dr. Shah, for the work you do and for sharing your incredible voice!

Introduction

Introduction of you and your work

My name is Dr. Nina Shah and I’m a professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, or UCSF. That’s where I focus mainly on multiple myeloma clinically.

That’s what I see in my clinic, but on the inpatient side, we see everything including leukemia and lymphoma. I’m particularly interested in immunotherapy, as it relates to multiple myeloma and cellular therapy.

This would include things like chimeric antigen receptor T-cells, or CAR T-cells, as well as natural killer cells, dendritic cell vaccines, antibodies, and T-cell engagers. All those exciting immunotherapies that are coming down the line.

I also have a secondary interest in patient experience, including quality of life, patient-reported outcomes, and some life coaching applications that we’re trying to use to improve patient experience.

Understanding Multiple Myeloma

What is multiple myeloma in human terms?

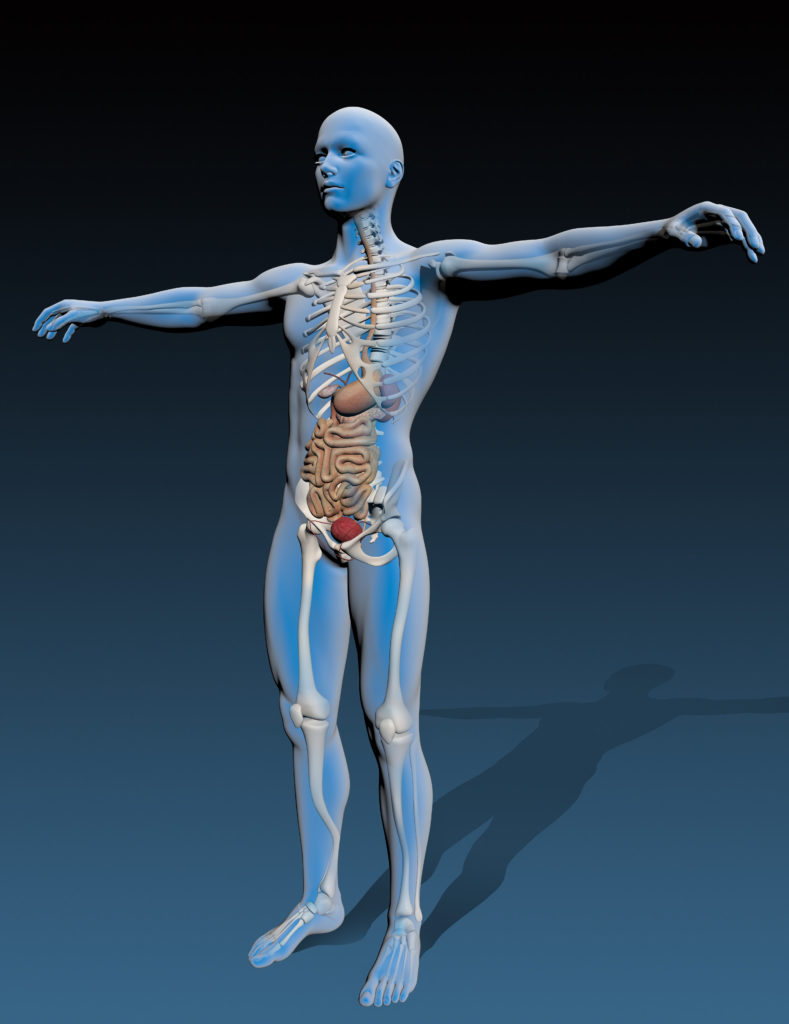

Multiple myeloma is a cancer of a cell called plasma cell. A plasma cell is part of your immune system. Normally your immune system is made to fight viruses and bacteria and one of its soldiers is called a plasma cell.

Particularly, plasma cells are supposed to produce antibodies, which we’ve heard a lot about recently. COVID antibodies, antibodies to zoster, all these things.

These antibodies are proteins that help you fight and tag bad things so your immune system can know to kill those things.

In the case of multiple myeloma, one of these plasma cells goes haywire. It grows out of proportion to the other cells, and that’s really the definition of cancer.

When one cell gets selfish and replicates its own clone, it takes up the resources of the other cells. That’s what happens in multiple myeloma.

One plasma cell grows and it starts taking up the space in the bone marrow. It starts producing a protein that eats the bone around it and that’s why people can have holes in their bones, or lytic lesions.

Then the protein that it produces—that antibody is now one antibody. It’s not a variety of antibodies. It’s just that one clone.

That’s why you will often hear the term monoclonal protein or monoclonal or clonal protein, M protein. That’s something that we can use to measure how many plasma cells there are.

It’s like the petals on the flower; the more petals you see around, the more you know they have flowers and that’s what we often use to measure in the blood.

The proteins that are produced from these cells can be in such high quantities that they also can have detrimental effects. That’s why some people with myeloma will say, “Well, my light chains were really up.”

That’s part of that M protein, those antibodies, and they can clog up the kidneys.

You hear about multiple myeloma as a disease that affects almost every part of the body—the bones, the kidneys, the blood system, and it all comes from having this one immune cell get a little out of whack. It’s supposed to help you, but in this case, it’s harming you.

What are the chances of it relapsing or being refractory

Unfortunately, multiple myeloma is considered an incurable disease, but it is a disease that one person can live with for a very long time.

We have patients who’ve lived 10, 15 years with it. It really depends on where that myeloma is going and what it’s like.

Sometimes we can predict that and sometimes we can’t, but on average, our standard myeloma patients are living longer than 10 years, at least, because we have new therapies.

What I tell all myeloma patients I meet is that, “You’ve been newly diagnosed and we’re starting therapy on you. We’re hoping that we can stretch out this time as long as possible so that we can have this first remission, meaning the first time you have a response that lasts as long as possible so that you don’t have to worry about it and you get back to your life and start being a person and not a patient.”

First Line Treatment

First line of myeloma treatment

For anybody who’s been newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma, it is very overwhelming because there’s a lot of information about what this disease is, then what is your life going to look like, what treatments are there and how can you predict what’s going to happen to you.

Those are all unknowns and if we had a crystal ball, of course we would be able to tell you as best as we could, but we often don’t know.

Combination (induction) therapy

What I usually tell the patients is that we’ll start off with some combination therapy. This is called induction therapy, and it’s usually a three-drug combination.

The backbone of that usually is some steroids, like dexamethasone, the drug everyone loves to hate, and then two other drugs. We usually combine those three drugs and we give them for three or four-week cycles. Those are pockets of time.

VRd induction therapy

There can be a variety of choices that we may give upfront, and this is really dependent on what the physician’s style is. The standard treatment is VRd, or Velcade or bortezomib (they’re the same thing), Revlimid or lenalidomide, and dexamethasone.

VRd side effects and management

- bortezomib (Velcade) side effects: neuropathy or numbness in hands and feet

- lenalidomide (Revlimid): fatigue, diarrhea

- dexamethasone: energy level changes

The major side effects from the bortezomib or Velcade are potential neuropathy, or numbness, tingling, and a weird sensation in your hands and feet. A lot of times patients will say it’s worse at night.

We’ve tried to get around this by changing the dosing schedule and doing it weekly instead of twice weekly, although it was originally approved in a twice-weekly fashion. Sometimes, for older patients, we may reduce the dose.

The Revlimid often can make patients experience fatigue or diarrhea, but it’s generally well-tolerated when you do it upfront and when newly diagnosed. I would say more of the Revlimid symptoms happen after the transplant.

The dexamethasone can make you nutty. It’s like people are cleaning up their house all day long on the first day, and then on the second day, they crash. Their spouses now avoid the dexamethasone day.

Alternatives

There are other alternatives to the first one. Sometimes instead of using Velcade or bortezomib, we’ll use a drug called carfilzomib. This also works in the same mechanism of action, but has been studied in later lines. It’s also a very effective drug that has another side effect. It affects the blood pressure and has potential slight effects on the heart.

For example, if a patient comes to me and they’re healthy, except they have diabetes and they have really bad neuropathy from their diabetes, maybe a better choice for them would be the carfilzomib and not the bortezomib with Kyprolis and not Velcade, as their trade names.

That’s how we go about thinking about the side effects of these therapies.

High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant

After several cycles, if you’re healthy enough, we often would take you to a high-dose chemotherapy autologous transplant, or just transplant for short.

Stem cell transplant is what I would consider to be part of the standard of care for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. You may not hear that from every doctor, but I like to do transplants.

The reason for that is that while those three drugs at the upfront, the Velcade, Revlimid, and dexamethasone, are like the soap and sponge for cleaning a dirty pot.

But the melphalan, which is the transplant drug, is the Brillo pad. It really digs in and gets the deep myeloma cells that you couldn’t get. It’s another way of being smarter than the myeloma.

This process involves two things. Since we can’t give you a very high dose of chemotherapy without damaging normal cells, before we even give that dose of chemotherapy, we have first to collect blood stem cells so that your blood will recover from having that dose of chemotherapy.

We always initially do a stem cell collection. This is an outpatient procedure and can take about a few days. We put a big catheter, usually in your chest wall, or a big IV in your arm. Then we take out a bunch of blood and filter out those stem cells after having given you some medication to get those to your blood.

Usually about a week for it between the injections and the procedure. Then after that, we do part two, which is the actual transplant. That’s when patients are, in our case, admitted to the hospital, although you can do it as an outpatient.

They get one dose of this chemotherapy. Two days later, they get replaced with those stem cells. We thaw them and give them just like a blood transfusion; it’s pretty anticlimactic.

For the next two weeks or so, these patients recover from these traditional chemotherapy yucky side effects:

- nausea

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- hair loss

- infections.

Of course, they need transfusions because we’ve completely obliterated the blood system and we have to take time for those stem cells that we gave to come back and grow and repopulate.

That’s the time that you’ll feel those traditional chemotherapy side effects that are less present with the newer Velcade, ReV/Dex.

Those are the new chemos, but this is like the old-school chemo. It does its job because we know that patients who get transplants early and get it upfront as a planned procedure actually do better as far as how long their disease is in control.

Maintenance therapy

After that people would generally go on to maintenance therapy, which right now is just one pill of low-dose lenalidomide, also known as Revlimid.

That pill and that factor can go on for five years or as long as they can tolerate the revlimid. It’s not always easy to tolerate it, but most of my patients can tolerate some of it.

You can go back to work, go back to having a life, go back to their family life.

»MORE: Read more patient experiences with Revlimid (lenalidomide)

Shared Decision-Making

What to ask your hematologist

As far as understanding what they should know and what they should ask their doctors, it’s important to know what kind of myeloma you have because you want to be able to follow your own labs.

Being able to follow your own labs when you get them is an empowering thing.

Sometimes it’s an anxiety-provoking thing, but I find in general it’s empowering because you and your doctor can have a really good conversation about trends and where things are going.

You feel like you’re really a part of the decision-making, which you always should be.

The second thing is that it’s important to know what your cytogenetics or FISH studies are. These are DNA characteristics of the myeloma cells and how those myeloma cells are prone to grow or not grow based on what we find in these studies. That can help us determine the risk.

When we talk about risk, it’s how aggressive the myeloma really is, how likely it is to come back sooner than later. These are all parts of the discussion that are important to have with your doctor at the time.

There’s also other parts of discussion you want to have like supportive care. Other things you should be doing, for example, to make your bones stronger and to make you stronger to go through this process.

Higher risk versus standard risk

When we think about high risk versus standard risk in general, that means the malignancy is more aggressive.

In the case of multiple myeloma, high risk is defined by factors like a staging criteria. This staging criteria is called the revised ISS (international staging system). We use the beta 2 microglobulin and the DNA characteristics as well as LDH to determine. That’s a lab value that’s often overlooked, but is useful to help us figure out how myeloma cells like to grow.

Then there’s what we call cytogenetic risk. These are very specific findings in the DNA studies, you’ll see most commonly called cytogenetics or FISH. That’s a short term to talk about how these pieces of DNA look.

When we find things like 17p deletion, or deletion 17p, or translocations, that’s when two pieces of DNA break off and hook back up with each other. You may see that there’s a piece of 11 with a piece of 14 or a piece of chromosome 14 with a piece of chromosome 16.

We often see that there are some patterns of high-risk cytogenetic or FISH findings. Then we can say to the patient, “Your myeloma cells are getting a genetic signal that tells them to grow,” or, “They’re not getting a signal that tells them to stop growing.”

Then we know that those patients may have more aggressive disease. That’s what we talk about risk—either by disease burden or by what propensity or likelihood it is for these cells to grow.

Is it standard that doctors pursue these tests

Thankfully, we have grown a majority over the past 10 years and it’s almost always standard. In fact, I can’t remember the last time I didn’t have a bone marrow test that had this. At least FISH is sent, sometimes cytogenetics. They’re two sides of the coin. It is very critical that it is sent.

Even for patients who may have had a biopsy done, for example, on a bone in their back, because there was something that was biopsied by a neurosurgeon that turned out to be consistent with myeloma.

I still insist on FISH being run either on that specimen if it’s possible, or repeating with the bone marrow biopsy. It is so critical to get that DNA information.

Describe how you manage the treatment decision-making process with patients

It’s really important for the doctor and the patient to be partners in this process. It must also involve the caregivers because they’re part of the story too.

What I do is I try to give the patient background information so they can understand the pathophysiology. It makes them understand what’s happening in their bodies. Then we talk about what to consider when picking one treatment over the other.

A lot of times treatment decisions are based on what the patient himself or herself looks like. Some people may have kidney dysfunction, some may be older and frailer. Some people may have preexisting conditions like diabetes, et cetera. This information helps us to understand what treatment will do the least harm.

Many of these treatments do equal good, but we want to do the least harm.

It’s really important for me to know a patient’s medical history and what are the symptoms that he or she has. I can understand what would be a good fit for treatments and I can explain that to the patient.

Oftentimes, the patient and I, having spoken about their symptoms and some of their medical history, can come to an agreement based on the choices.

It’s hard because sometimes you don’t want to ask for recommendations that you don’t plan on taking. But you should always feel free to do that because it’s our job to give you the choices that exist and make recommendations.

Ultimately, you have to be okay with the path going forward.

Newer Multiple Myeloma Treatments

Proteasome Inhibitors

It’s a very interesting thing that the proteasome inhibitors exist at all, because it’s one of the few times where you can take advantage of something going wrong in the cancer cell.

The myeloma cells—the plasma cells—love to make proteins. They make that one antibody which is a real problematic thing, but it is a way for us to measure it. Because of that, their protein machinery is on overdrive.

The proteasome inhibitors work by irritating the garbage disposal of fat protein machinery. That then makes the cell extremely mad and it makes it die because it can’t get rid of all its waste.

That’s why these proteasome inhibitors are particularly good for myeloma cells because those cells produce a lot of protein. You generally hear about these drugs specifically for multiple myeloma.

New CAR-T-cell therapy

This is the BCMA-directed CAR-T-cell therapy and idecabtagene vicleucel or ide-cel. The trade name is ABECMA. You can look at any of those, we call it bb2121. Everything has five names.

It’s a way to take a patient’s own T-cells and genetically engineer them so that they will express a protein on the surface. That protein will specifically target a protein on the myeloma cell that’s called BCMA. It stands for B-cell maturation antigen and it happens to be a very specific protein that is on the surface of the myeloma cells.

These T-cells are engineered to recognize specifically that protein and those T-cells see the myeloma cells and they think, “Oh, you’re an infection, I better kill you.” That’s what they do. We take advantage of the T-cell ability to kill things that they consider foreign and these T-cells will bind to these BCMA plasma cells and kill them.

That’s what’s so exciting about it—it’s taking your own immune system and repurposing it to do its job of killing its myeloma cells.

This product was FDA-approved just this March of 2021. We’re very excited to start rolling in our clinic to make this available for patients as a standard of care after having received four prior lines of therapy.

Abecma side effects and management that you have to offer to patients and caregiver

Acutely, Cytokine Release Syndrome, or CRS, does happen and is like the worst flu you ever had. It’s appropriate because your T-cells are having a party with all the myeloma cells and that’s good. That means the T-cells are trying to fight the myeloma cells as they would any infection.

You do have fever and potentially lower blood pressure. Over 84% of patients had this in the pivotal trial, but very low grade, manageable with a drug called tocilizumab. It usually happens within the first day or so of getting these cells for Abecma. After that, it’s boring in the hospital thereafter, which is good.

There’s also an 18% chance of having neurotoxicity or confusion that’s also very treatable with steroids. After the first two weeks, it’s actually much better.

There is fatigue and some low blood counts, but we’ve just had an analysis of primary and secondary quality of life measures.

It showed that over time, going from time zero all the way to 6, 9, and 12 months, patients actually had improved quality of life with decreased pain and fatigue, and increased emotional and social functioning. This is very important in maintaining who you are, not just what you are as a patient.

Patient Response

The pivotal KarMMa study, which is the study that ultimately got this product approved, had patients with very heavily pre-treated myeloma. Median, so at least half the patients, had six prior lines of therapy. That’s a lot of therapy that people have had.

Usually, drugs get approved by the FDA for myeloma with a 30% response rate. That’s the bar, but here you have something with a 70% response rate and it’s actually upwards of over 80%, for the actual dose level that has been recommended to go forward. We think we can get 8 out of 10 people to respond, hopefully.

For those people, they can have a year without getting any therapy. Again, the progression pre-survival for most drugs with FDA approval in this setting is like two, three months. It’s not very long at all. To get 12 months a year without any other therapy is something that we’re looking forward to because our patients definitely want a break. They’d love to see our faces, but maybe not at the chemo suite.

This is something that is unprecedented, but we’re hoping that we can even improve upon this with future products.

Wave of Therapies

I think what we’re going to see now is this wave of T-cell therapy and immune therapy, which includes bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs). Those are like antibodies, but they engage T-cells and these are really exciting drugs.

Both of these are going through a lot more clinical trials. Although we have one product approved for T-cells, we have another one coming down the line, and we have to also alginate, which would be off-the-shelf T-cells, so patients don’t have to go through a T-cell collection. That will be coming down the line, not this year or next year, but soon.

In a concurrent way, we’re also going to have these T-cell engagers, which are not cell therapies. They’re actual drugs but they’re off-the-shelf drugs that can be given. The first dose or two needs to be given maybe in a hospital or monitored setting, but after that, it’s very well-tolerated. People will be able to receive this at their local oncologist’s office.

As we get more data for all of these drugs and understand safety and what’s best for treating patients, these will hopefully get FDA approved. There are already ongoing clinical trials to look at these agents, including the CAR-T cells in earlier lines of therapy, so we don’t have to wait for people to be on their fifth line of therapy to reap the benefits from this particular treatment.

Clinical trials enrollment process

If they want to set up a consultation, they can get to our new patient consult service and we try to see everybody within a week or two. Especially now with Zoom, it’s much easier. We can plug them in and we’re starting a queue now for people to get ready for this treatment.

At first, there will be a big line of people because we have people waiting and have been waiting for a year now, but we’re hoping that as 2021 rolls out, we’ll have a better way to space everybody.

Soon, we’ll be able to be in line as patients have relapsed disease, taking them and quickly getting them set up for Abecma.

»MORE:Learn more about the process of clinical trials from one program director

What is your message to the world and to patients

We are all limited by the same human things: time, cells, mutations, everything. I think this journey is one that has to be a journey of partnership between the provider and the patient.

It’s not anyone talking to you. It should be you having a conversation with your provider. The more that each of you is educated—and I get plenty of education from my patients—helps us understand each other better and ultimately make a better integrated and informed decision for your care path going forward.

Thank you, Dr. Shah!

More Hematologist Interviews

Rafael Fonseca, MD

Role: Interim executive director, hematologist-oncologist

Focus: Multiple myeloma, new drug development

Institution: Mayo Clinic

...

Farrukh Awan, MD

Role:Hematologist-oncologist, associate professor

Focus:Leukemias, Lymphomas, BMT

Institution:UT Southwestern

...

Nina Shah, MD

Role: Hematologist-oncologist, researcher

Focus: Multiple Myeloma

Institution: University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)

...

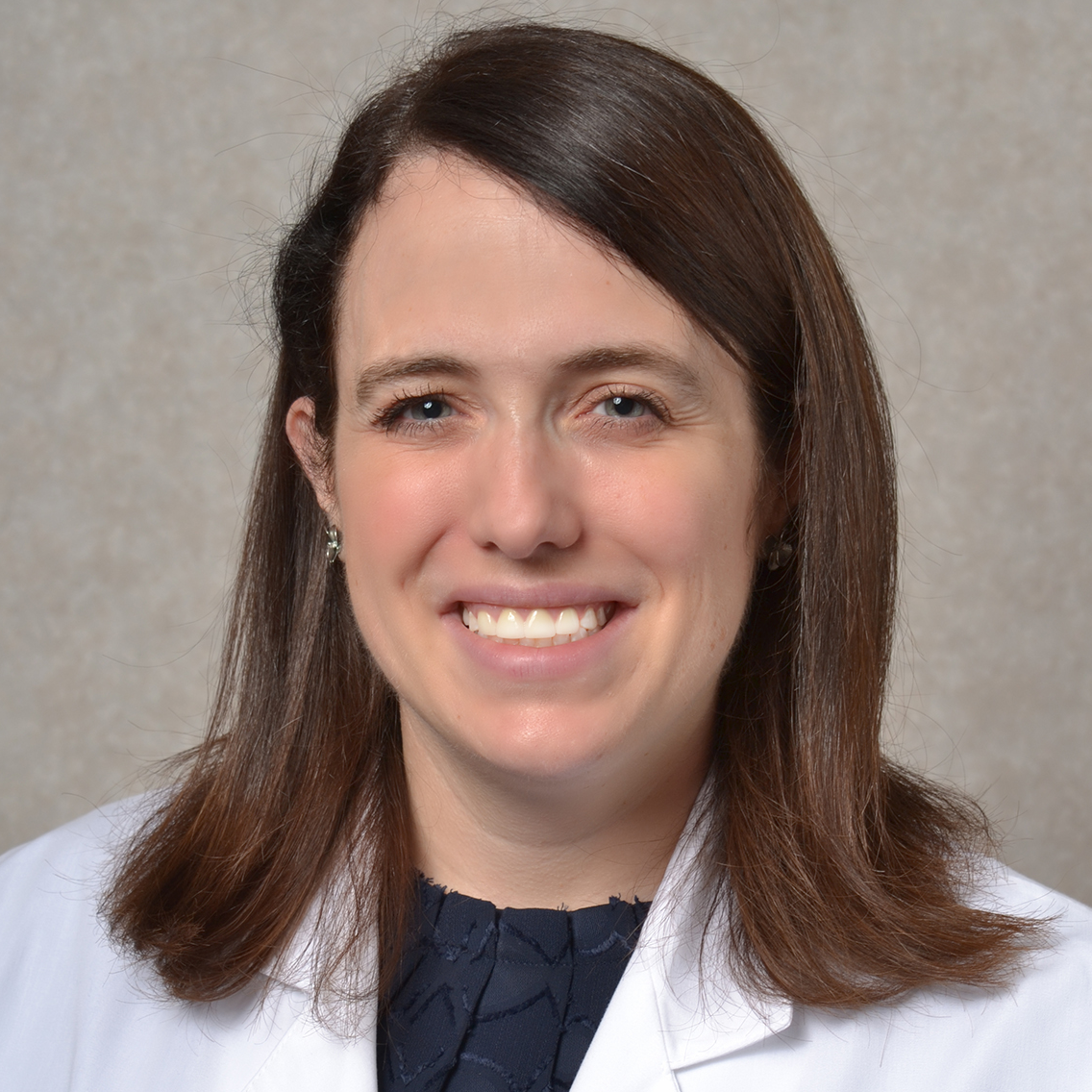

Kerry Rogers, MD

Role: Hematologist, researcher

Focus: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), Hairy Cell Leukemia (HCL)

Institution: OSUCCC-The James

...

Tim Fenske, MD, MS

Role: Hematologist-Oncologist

Focus: chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) & leukemia and lymphoma | CAR T, targeted therapy

Provider: Medical College of Wisconsin

...

Irene Ghobrial, MD

Role: Clinical investigator and professor of hematological oncology

Focus: Multiple myeloma, Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia, early screening, clinical trials

Provider:Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston)

...

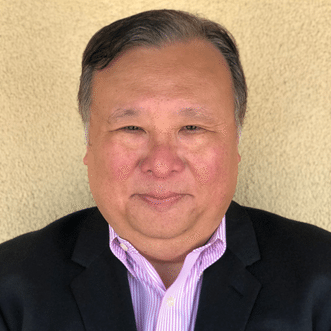

Edmund Tai, M.D.

Role: General oncologist, hematologist

Focus: Specialist in treating Chinese-speaking patients

Provider: Sutter Health (Bay Area, CA)

...

Jacqueline Barrientos, MD

Role: Hematologist, researcher

Focus: Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), lymphoma, 17p Deletion (Ibrutinib, Acalabrutinib, Venetoclax), IgHV mutation

Provider: Northwell Health (NYC)

...

James Berenson, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in myeloma and other blood and bone disorders

Experience: 35+ years

Institution: Berenson Cancer Center

...