Sonia’s Stage 1-2 Relapsed PMBCL Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Story

Sonia was 24 years old when she was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) subtype.

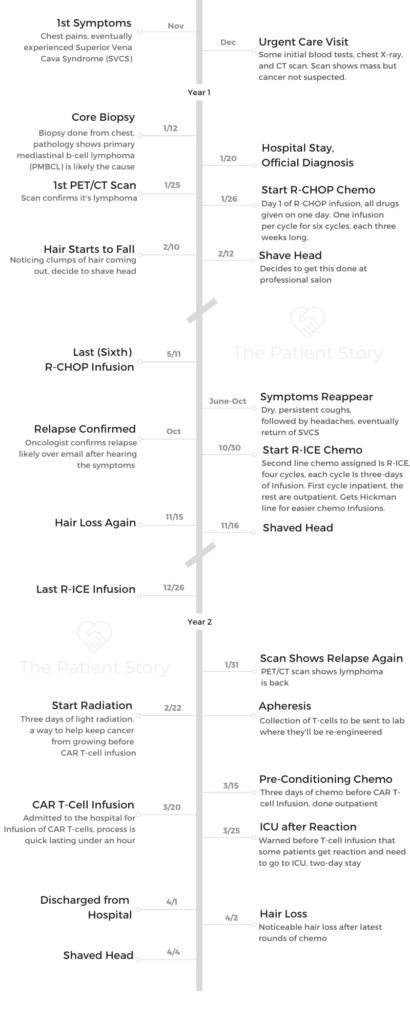

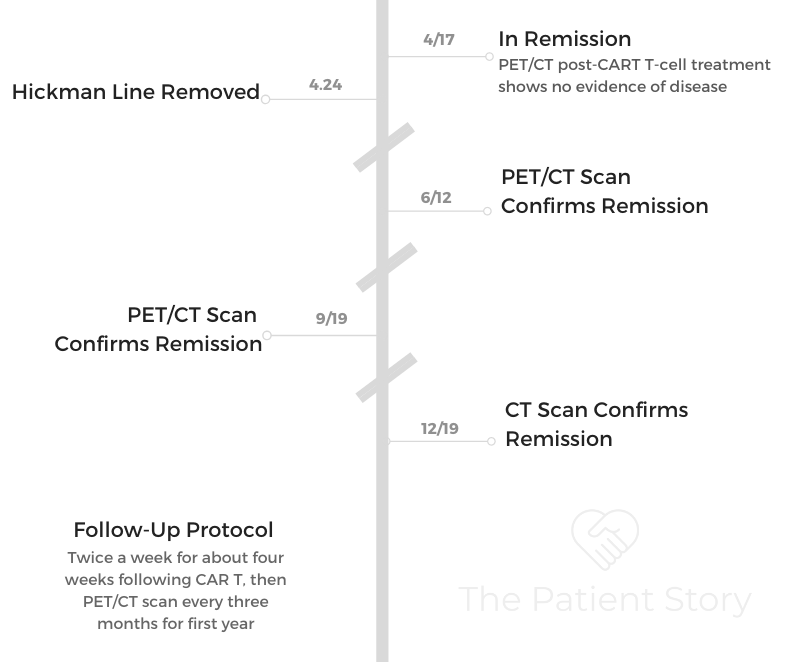

In her extensive story, Sonia details going through chemo before relapsing and undergoing more chemo before CART T-cell therapy. Sonia also describes losing hair (multiple times), what support helped her the most and survivorship.

- Name: Sonia S.

- Age when diagnosed: 24

- Diagnosis:

- Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Primary mediastinal large B-cell

- Stage 1 or 2

- 1st Symptoms:

- Chest pain

- Turned into superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS)

- Misdiagnosis: Costochondritis

- 1st-Line Treatment: R-CHOP chemotherapy

- 6 cycles, each cycle = 3 weeks

- Outpatient: go into clinic for hours-long infusion 1 day per cycle

- Relapse Symptoms:

- Persistent, dry coughs

- Headaches

- Return of SVCS

- 2nd-Line Treatment: R-ICE chemotherapy

- 3rd-Line Treatment: CART T-cell therapy

- Sonia's Full Story on Video

- Diagnosis

- Treatment Plan and Decisions

- How did you finally get admitted to the hospital?

- How did you navigate the waiting for answers?

- Figuring out where to go for medical treatment

- Did you have to do more tests before getting admitted to the new hospital?

- Describe the PET-CT scan

- Describe the contrast dye during the scan

- How did the oncologist describe the treatment plan?

- Did you have a choice with getting an IV, port or PICC line?

- Why didn’t you get a bone marrow biopsy?

- Did they talk about fertility preservation?

- 1st-Line Treatment (R-CHOP Chemotherapy)

- First Relapse

- 2nd-Line Treatment (R-ICE Chemotherapy)

- Stem Cell Transplant

- Second relapse

- CAR T-Cell Therapy

- After CAR T-Cell Therapy

- Reflections

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Sonia’s Full Story on Video

There’s varying degrees of gratitude, and at this point, I don’t even know how much gratitude I can express, but every day is a blessing.

It’s ironic and a cheesy cliché, but it’s true. Sometimes I think I can’t believe I’m still here and that I can do what I do. It’s a lot.

Sonia S.

Diagnosis

When did you feel something was wrong?

I remember this very clearly because I was in my first semester of grad school at Georgetown. I usually go home to my parents’ home in Maryland on the weekends. I was home alone on a Saturday night, I had ordered dinner, and for some reason, I felt some chest pain.

I thought it was maybe because of the food. I had no idea what it was, just thought, “This is weird and should get this checked out at some point, or at least monitor it.”

At the time I was approaching finals, really busy with school and life in general, so I waited a week or so before I decided to check out Student Health.

I think everyone knows how not-so-great Student Health can be in diagnosing things and checking you out. I didn’t think it was anything serious at the time; I just thought it was weird that the chest pain wasn’t going away.

The student doctor diagnosed me with costochondritis, which is essentially some kind of soreness with the chest bone or something. I got some painkillers or random meds that didn’t do anything.

When did you get some tests done?

I kept on ignoring it, letting it go until the end of semester since I had so much going on. It was closer to Christmas when I decided to check out the urgent care near my house, maybe get some blood tests or scan.

It was at that point where they found there was a mass in my chest.

At that point, we were still like, “Okay, a mass, that’s interesting. We’ll just need to follow up with another doctor.” We were referred to a surgeon at Georgetown. We had to schedule it for after New Year’s because of the holidays. I, myself, was traveling.

This chest pain was still going on, and it grew worse until I got back from vacation. We went to the surgeon, who said, “There’s a mass. We need to do a biopsy before we take it out.” They thought it was a benign mass that they would take out.

What scans did they do?

They did an X-ray, then eventually they did a CT. They said it was a mass, but they didn’t know if it was malignant or cancerous. It wasn’t until after the biopsy that confirmed everything. I walked out of the surgeon’s office. It was like, “Okay, we’re done with you. You’re going to need to go to an oncologist for this.” It was all so quick.

Describe the biopsy

They did a core needle biopsy. I was under. They take a small sampling of the tumor or mass. That’s the sample they used for diagnosing everything.

How long did the biopsy results take?

It wasn’t very long, probably within a week.

Cancer hadn’t even crossed your mind

No, it was still, “I’m going back to school,” or, “I might have to take a couple weeks off for the surgery,” because I was told I would need surgery.

How did you learn your results?

The biopsy was a separate thing. The surgeon had received the results. We were going in for our next consult, getting ready to get the surgery.

That was when he told us it’s not benign, it looks pretty malignant, and we’ll refer you to an oncologist. That was about it. He said, “Sorry, this is not for us.”

»MORE: Read different experiences of a cancer diagnosis and treatment

What was your cancer stage?

They weren’t really clear, and I don’t think at that point it mattered. I remember they said, “It doesn’t matter if you’re stage 1 or 2; you’re getting the same treatment.” So I never really looked that much into it, as long as it wasn’t stage 3.

Treatment Plan and Decisions

How did you finally get admitted to the hospital?

It was awhile before we decided to figure out the oncologist because we were still navigating everything. We had an appointment scheduled for the following week, but that weekend the chest pain was getting a lot worse, to the point where my face started to swell, and I was really worried about that.

My face was getting really bloated. The pain was getting worse. I was still in my apartment in D.C. My mom was still at home listening to me describe these symptoms.

She was like, ‘This is getting really serious. I need to contact the hospital to let them know we can’t wait till next week to see the oncologist.’

My mom faxed all my medical records to every local hospital she could find. The fact that she even needs to fax medical information these days [is crazy].

Johns Hopkins was the first one to respond. That’s how I got admitted the next day. They knew this was SVC, and it could get serious and deadly very quickly. I was admitted immediately.

They gave me some steroids to calm it down a little bit. That was when the bedside manner, he comes in and tells you, “Yes, this is lymphoma.”

I knew it, but that was when it was confirmed. He said I’d have to start chemo the next week and presented my plan.

How did you navigate the waiting for answers?

It was me and my mom in that surgeon’s office. We came in thinking we’re getting surgery. Then we get thrown for a loop.

I don’t know about your parents, but I don’t think any parents would ever imagine this happening. My mom has always been the very upbeat, positive, happy type of person. Even with some terrible news such as this, it’s crazy to say this, but I think she’s already pretty resilient due to a lot of other circumstances in our lives.

Both her parents passed away from cancer, so this is something really close to our family. She’s also really good at hiding her emotions, so I’ve always been amazed, to this day, how well they hid it throughout the journey, not only in the beginning.

We were just processing everything. People assume once you’re given that diagnosis or told this is actually malignant and could be cancerous, that your whole world falls apart.

But it takes some time to even process that information. It’s not just, “Oh it’s the end of the world!” It’s that this is the new life we’re going to deal with, and we’re going to deal with it together.

Figuring out where to go for medical treatment

This is another thing that was pretty frustrating. I wasn’t even sure myself where I would be treated because I was in school in DC, so we thought maybe we’ll try Georgetown. But my parents are closer to Baltimore, so maybe I should stay with them, and they can take care of me.

We consulted both Georgetown MedStar and Johns Hopkins around the same time, within the week or 2. We were trying to get second opinions, thinking about where I should be treated.

Ultimately, we decided on Hopkins. It was the best choice because it was most convenient for my parents to come and see me and work out everything.

There was really no time to consider, “Do I like this person more or the other?” It was really just, “What’s more convenient?” It would have been either a 30-minute drive or over an hour, depending on traffic. When it comes to chemo and having my parents take time off of work to drive me to and from treatments and things like that, there was really nothing else to consider.

We thought Hopkins is great, and it’s true, Hopkins is really good at what they do. Might as well just do that. Didn’t make much more sense to go to Georgetown, so we stuck with that.

Did you have to do more tests before getting admitted to the new hospital?

I didn’t do anything else after the biopsy. They needed to check all the records. I did the biopsy at Georgetown, then they needed me to transfer my own records through them to another hospital. It was a whole ordeal.

Honestly, they scheduled everything when I was admitted because of my swollen face. They gave me the meds and gave me the schedule. “You’re coming in next week, and you’re going to start.” I didn’t do much else. I may have done one more scan at that point, but it was very fast.

Describe the PET-CT scan

A PET scan takes all morning or all afternoon. Usually it’s in the morning because you’re not supposed to eat for at least a couple hours. Patients get all this information usually the day before, making sure they’re following the procedures.

You go in on an empty stomach, no fluids either. You have to drink something, but it depends on each hospital. For some it’s white, and some it’s a lemon flavor. There’s different flavors. It’s a contrast, but also this other liquid you drink that lights up your body, making it easier for the scans to read your body.

You sit there for about an hour or so drinking that, and it’s usually in a room where you’re by yourself. It’s better that your body is warm and not cold for some reason. They’ll usually give you a blanket to keep you warm.

Sometimes they say you can’t use your phone because you can’t have brain activity, but it depends. If they’re not scanning your brain or don’t care about that part, maybe it wouldn’t matter.

I was peacefully waiting in the room drinking that fluid. The scan itself doesn’t take that long. They call it PET-CT because it’s 2 different scans.

I did the PET first, which was maybe 10 or so minutes. The CT was maybe 5 minutes. [I was] in and out of there pretty quickly.

It was pretty much an all-day process because depending on the hospital you go to, you may also be able to meet with your doctor the same day after.

Mine are usually in the morning. I will have lunch with my parents at the hospital, wait for the results and then meet the oncologist after lunch for him to explain the initial results with me.

Describe the contrast dye during the scan

That’s CT with contrast. Usually for me, I always got them with contrast, so I always got the IV in if I didn’t already have a line in. They warn you it feels like you’re peeing. You get a warm feeling down there.

I would have the IV on my arm, but I think I grew sensitive to it. Every time it went in, it would burn my veins so much. After a while, I thought it was just part of it. Afterwards, my veins are fine. It’s just what I have to deal with every time I get a scan.

It’s never fun to have to go get the scan anyway, because I don’t have a port or line in right now, so even getting the IV in takes awhile. If anything, it got a little worse because my veins were crying from the contrast every time it goes in.

How did the oncologist describe the treatment plan?

Doctors will say different things. Mine at Hopkins recommended R-CHOP. He said that would be outpatient, once every 3 weeks. Mine was usually every Friday. I’d go in basically all day. The first one is usually a little slower because they don’t want to give it to you all at once.

It was for 6 cycles. I started late January and ended around early May. That was half a year of R-CHOP. There’s another one they recommended, R-EPOCH chemotherapy . It was another option, but it would have involved more consecutive days each cycle.

We brought that up with the Hopkins oncologist. He said it’s a slight difference in success rate. He said this is just what we do.

It made sense because it’s Hopkins. If you go to a big hospital like that, they have their ways of doing things. If you bring up any other treatment, they’ll be like, “We could, but no.”

Part of that second opinion during that 1- or 2-week period, we went to Georgetown MedStar. The oncologist there said, “Yeah, we can do R-EPOCH if you want.” That one was completely like, “This decision is up to you. If you want to do this, we’ll do this. If you want to do that, we’ll do that.”

Did you have a choice with getting an IV, port or PICC line?

No, I got an IV each time I went. I think it made sense because I only had go in once every 3 weeks, and it was for only one afternoon or one day. At the time, my veins were amazing for a young person who had no prior experience to this.

It wasn’t until I relapsed a couple months later when I started R-ICE — that was when each time I had to go in 3 days every 3 weeks. That was when I got the Hickman line, which is a central line, 2 or 3 tubes that literally pops out of your chest. It’s not like a PICC line that’s hidden; it’s popping out.

They had wanted to insert a PICC line, but for some reason my veins just weren’t having it. They couldn’t get in it, so the Hickman was the last effort. “This will work. We’ll just do this.”

It’s not the most attractive or convenient because you can’t wear anything lower unless you want people to see. There’s a whole regimen. You have to clean it. It’s a lot.

Why didn’t you get a bone marrow biopsy?

I didn’t know that was part [of the process]. I think they just went by the biopsy and PET scan and were good with going with everything.

Did they talk about fertility preservation?

No, when I first started, this was all happening within a week or 2, so there was no discussion at all. I hadn’t even thought about that. I was just like, “Okay, let’s do this. We’ll be over with this in a couple months.” Very naïve of me.

No discussion at all or even thought about it. Maybe they mentioned it briefly, but there was no discussion of, “You should get this done.” It wasn’t until after I relapsed where they said, “We’re going to put you on R-ICE, and you’ll be on track for a stem cell transplant. Has anyone talked to you about fertility?”

I said no, and they offered to refer me to someone. I eventually did speak with someone over a year later, when I was in the process of preparing for the transplant.

In the end, I decided not to go through with it because at that point, I was really exhausted by all the medical treatments.

Just listening to the fact that I would have to stab myself in the belly every day for a while, I was like, ‘I’m just tired. Can I not?’

This was not something I decided immediately. I was with my boyfriend, who was long distance. We went through the options and with this, there was a small chance that it would even be successful — at least that’s what I was told.

I thought if there’s a small chance, and I don’t have to pay fees every year to maintain it in storage. I also didn’t know if insurance would cover it, because it was that year when Maryland passed the law where insurance had to cover cancer patients’ fertility treatment.

For some reason, my insurance rejected my appeal. I don’t know why. I think everything compounded together — the insurance rejection, the small chance of it working, the fact I’d have to continue paying (storage fees), and not sure I want kids. From all of that, just thought not going to go with it.

It’d be great to know if I’m still able to have children, but I’m still getting periods. They’re pretty normal. I think it should be all okay.

»MORE: Fertility preservation and cancer treatment

1st-Line Treatment (R-CHOP Chemotherapy)

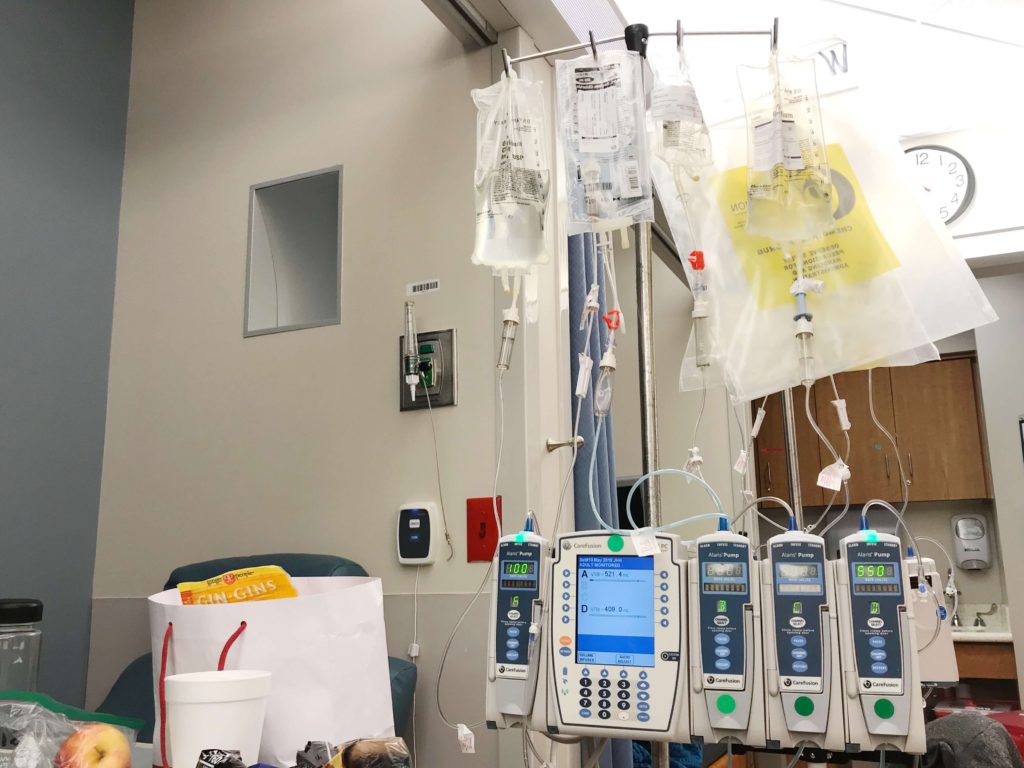

What were the infusions like

The infusions usually started in the mornings because they know you have a long day. The first one was all day because they do try to ease you into it. Even in the beginning, it’s not like you go in and they immediately give you chemo. They give you fluids, and they give you some Benadryl to make you sleepy. They do a lot.

It’s maybe 2 hours later after you arrive when they actually start everything. When they do, it’s pretty uneventful, to be honest. It’s like any transfusion or blood draw, except for the part where, depending what you’re getting, they’ll get some extreme outfits.

They’ll wear some protective gear to protect themselves. You’re thinking, ‘Wait, you’re wearing all this for something going inside my veins?’

It makes sense because they are exposed to this constantly, so maybe that’s the concern there, but at the same time, I’m like, “Oh man!”

Otherwise, it’s pretty uneventful. I brought my laptop and books every time, but I decided I didn’t have the bandwidth to even read. I watched a lot of Netflix.

My parents are amazing. They went with me to every single appointment. They sat there on the phones just talking to each other, keeping me company. They’d bring bags of food every time, snacks and things like that. It’s an all-day affair. They’d have to get lunch down at the cafeteria.

My parents are immigrants who have been here for awhile, but at the same time, American food is just meh — they’ll have it if they need to. I felt a bit bad, but it was all the hospital had. They’d get Subway or random cafeteria food that wasn’t healthy at all, which was ironic!

I was, of course, the youngest person there always.

It depends on the center, but I was in an area where there were a lot of other patients. You don’t get your own room. You get your own nook. Sometimes it’s a bed near the window, an actual bed, or a reclining chair in front of a TV.

I had a choice. Sometimes they’d ask, “Do you want the bed or the chair?” Sometimes it’s busy with people getting treatments, so you don’t have a choice. It’s just chilling at your own nook for basically all day.

Having company at the infusions

[My parents] were with me because this was pre-COVID and pre-visitor restrictions, which I’m really grateful for. I can’t imagine going through all of that by myself. I would feel so lonely. This is something that is so important, to have that support with you if possible.

Anyone who can be there to support you, even if you’re not talking and just sitting there for hours.

When did you feel the R-CHOP side effects?

That day, I didn’t feel much of anything. Maybe I was very thirsty. But definitely starting the next day, I was feeling weird. I wasn’t sure how to describe it. I think it was nausea, but I didn’t know what it was at the time.

I remember very vividly because I was still part of this club on campus, a magazine club. I was still editing for the campus publication. We had a meeting that Saturday, the day after I got my first chemo.

I still had my hair. I was like, “I’m good. I can go to this meeting.” I was so ambitious. Yeah, don’t. After you get your chemo, try to stay home as much as possible, get some fluids, and get some rest.

But I was so ambitious thinking, “I can do this. I can go to this meeting, and I can still edit for this magazine.” I did still work for them, but I remember I was feeling sweaty, feeling weird during that whole meeting.

My parents drove me there. They’re amazing, because at this point I had moved out of my apartment and was back at my parents’ house. They drove me back and said, “How do you feel?”

As soon as I got in the car, I was like, “Not good.” Drove home, immediately rested for the whole day because I felt so nauseated. I realized, “Okay, I can’t do this. I can’t go to school after chemo.”

I’m glad I’m taking medical leave of absence for the whole semester and taking things really slowly. The next few days, I was trying to get the rest.

When did you start losing your hair?

My hair started falling out a couple days before my second treatment, so within 2 weeks or so. That was interesting just because it started off slowly. When I would run my fingers through my hair, some things would come out. But then it accelerated super quickly.

At one point, maybe after I washed my hair, I’d see the shower full of hair. I’d see literally bald patches. That was really bad. I decided I don’t want to see this anymore. I don’t want to keep looking at my hair falling out, so my mom helped me shave.

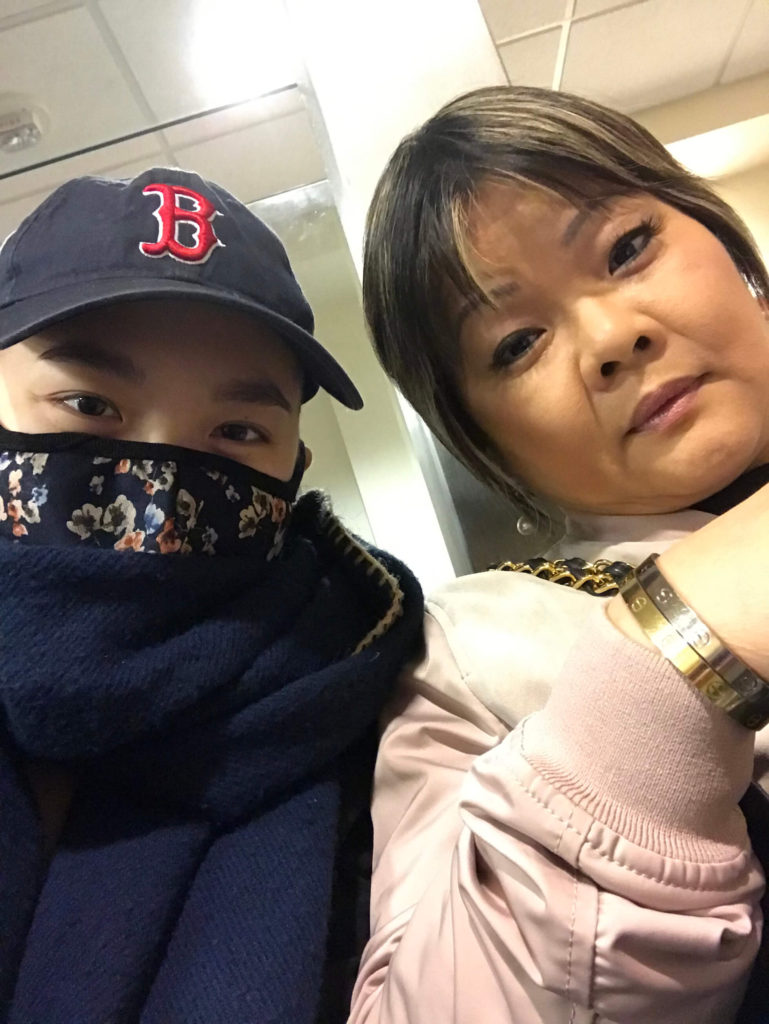

My mom shaved the second and third times I had to shave, but the first time I actually had to go to a hair salon nearby because my mom was a little worried. She hadn’t dealt with this before. We went to a hair salon, saying we need to shave. My mom casually mentioned that I had cancer, which was really awkward to tell people.

They were like, “Oh my gosh, of course!” They ended up not charging us, which is so kind of them. They charged my mom because she got a cut as well, a brief trim.

I got my hair shaved in public in a salon. I just wore a hat at that time because it was still around winter, so it was okay to be covered.

How did it feel getting your head shaved?

For most girls, they define their beauty by their hair in a way. If they don’t have hair anymore or if they’re bald, they just don’t feel pretty. That’s definitely how I felt.

But I don’t think I really knew how influential that would be until after it all happened. As it was happening, it was like, ‘A stranger is shaving my head. I’m not going to get that emotional. I’m going to be fine.’

Even after that, I put my hat back on, bundled up with my scarf. You couldn’t really tell. I was like, ‘Okay. It will be okay.’

After that, every time I looked at my hair, it was almost amusing. My parents would say, “You’re bald. I’ve never seen the shape of your head! Your beautiful head!” They’d want to touch it and say, “Wow, it’s so cool! You have a great head.” You’d get random compliments when you’re bald.

Everyone is pushing and encouraging you, saying it’s okay. But when it starts growing out — even now it’s pretty short — it just doesn’t feel the same.

Of course, it’s different for everyone. Maybe it’ll be more emotional for others. Maybe others are like, “I’ve always wanted to shave or try this.”

For me, it was, ‘I have no choice. I can’t do anything else.’

»MORE: Dealing with hair loss during cancer treatment

Describe the post-treatment PET-CT scan

At Hopkins, because it’s such a huge hospital, they have a lot of fellows and students. Because they have so many patients, my primary oncologist actually took a back seat throughout my treatment. I was really working with a fellow.

The fellow told me that the last scan was basically okay. It was never really clear, to be honest. They were just saying, “It looks pretty good. There’s slight activity that’s likely scar tissue.” They dismissed it as scar tissue, and I accepted that.

First Relapse

Feeling symptoms again

I took that as an okay to essentially go abroad after that because, again, ambitious me. I didn’t want cancer to stop my life, so I had received a fellowship to study abroad in Taiwan. I said, “Hey, can I do this? Is it okay to go?”

He had told me, “I wouldn’t really recommend it. You just went through all this. You still need to do check-ups, but as long as it’s not a third-world country where you can’t get blood tests, then it should be okay.”

I said, “Okay, I guess I’ll do it.” At that point, I didn’t feel the need to stay because this felt like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for me, so I decided to take it.

To this day, I don’t regret it because things happen for a reason. I had left around June and had just finished treatment in early May. I arrived, and within a day, I started coughing. That wasn’t my initial symptom. I hadn’t been coughing before all this started. It was really just the chest pain.

This was a new thing, and I chalked it up to pollution or a new environment or anything. I even saw a cancer center in Taiwan just to make sure and double-check everything is good. Everything was good.

But the cough was consistent. It was a dry cough, so that made things seem like they were really okay, that it was just something. That cough lasted from June through my relapse in October, when it was confirmed.

The cough only got worse. I couldn’t even get a word out without coughing something. It was really awkward, too, because I was doing an internship. I was starting classes with people and wearing a hat, too, because I was still pretty bald.

You chose to keep the cancer private

I feel like I was the odd one out. I think cancer really affected my outlook in terms of trying to make friends and trying to make connections. I didn’t want to be like, “Hey! I’m Sonia. I’m on this fellowship, but I also just had cancer.”

Eventually some people did figure it out because I was very public about sharing it on my blog. If they added me on Facebook or anything, they would have found out some way or another.

I still didn’t tell anyone except for my boss at my internship. It really prevented me from getting social. I tried to hide everything, even though I had this weird cough and was bald.

When did your symptoms noticeably worsen?

Closer to October is when I realized this was actually getting really serious. The swelling came back. I was getting serious headaches. I was in communication with a different fellow at Hopkins. She’s like, “Keep track of it. It should be okay.”

I decided to book a flight back home at some point just to get everything checked. That was one of the scariest moments of my life. I remember when I was at the airport in Taiwan, I was already starting to get winded.

When I was home, it was really bad. I was carrying my luggage. I was carrying everything, and I couldn’t even walk without taking a break. I couldn’t breathe. It felt hard to breathe. I was like, “This is really bad.”

In the meantime, I’m emailing my oncologist, saying, ‘I’ve just arrived. What do I do? Should I go to the emergency room?’ They said, ‘Yes, go now. The symptoms you’re describing sound like you’ve relapsed.’

This was through freaking email on my phone. When I just landed, I’m emailing this fellow and just describing all the symptoms. I’m like, “I can barely breathe.” They’re like, “Yeah, you relapsed.” That was what happened.

You wound up going to the emergency room

My parents picked me up. We went home. I ate dinner. It was around nighttime, and we were just preparing because we were thinking, “Let’s go to the emergency room to get things checked out, to at least get some blood tests and then a CT scan.” Obviously, with a PET scan, it requires more insurance approvals, so the least they could do was a CT scan.

That was a nightmare in itself. In addition to the nightmare of relapsing, there was the nightmare of going to the emergency room because I had been dehydrated, I guess.

I hadn’t drunk enough water because I was around the world, so they couldn’t find my veins. They had 3 different nurses poke me 8 times at least. This was 11 at night, and they couldn’t even get a needle in my arm.

They managed to get some blood, but they couldn’t get the IV in for the CT scan, so we spent a few hours there for essentially some blood draws.

Admitted to the main hospital next day

It was the next day when I could actually go back to Hopkins, and I was admitted immediately.

Everything else from that was a blur because they immediately gave me chemo. It wasn’t even a question. It was, “Describe your symptoms,” and, “Okay, we’re starting chemo tomorrow. We’re going to monitor you, and you’re starting.”

In the blood draw, they saw a certain indication — a level was extremely high. It was the LDH (lactate dehydrogenase). That was the indication that the body’s fighting off something.

They were able to do the CT scan at the hospital, thankfully. While I wasn’t able to do it at my local general hospital, they were able to do it before I was admitted and then started everything.

2nd-Line Treatment (R-ICE Chemotherapy)

Preparing for 2nd-line treatment

This was a little different in that I was assigned to another team this time. That’s the thing. I was bouncing back and forth. I don’t even know what team I was on at that point.

I saw a new oncologist, saw a new doctor, saw a new fellow every time. I was assigned to this group.

I remember lying in the hospital bed, and a team of people would come. All of them would be fellows, and there’d be one [attending].

Every time they’d come see me, the whole team would come. Maybe one of the fellows would speak to me directly. Before everything started, they told me this would all be in preparation for a stem cell transplant. I’m not just getting these 4 cycles and done with it. I’m getting these 4 cycles and then moving on with the transplant.

I was still a little bit confused, to be honest. I wasn’t sure why I couldn’t get this and be over with. Through all these treatments, your blood cells are going to be diminished down to basically nothing. It’d be really hard for your system to just make more blood cells, so I guess that’s why [the need for] the stem cell transplant.

I was on track for that. They said 4 cycles. After 2, I was back in remission, which is a good sign. But for some reason, they still wanted to continue because that’s part of their process. Even though you’re in remission after 2, you have to do 2 more, which was not fun.

Describe the R-ICE chemo cycle

R-ICE is 3 days outpatient, another couple hours each day. They’ll distribute it over 3 days, every 3 weeks, for 4 cycles. I remember I tried to debate with them, saying, “Can we only do 3 or 2?”

Getting a second opinion on treatment options

While I was doing all this, I went to National Institutes of Health (NIH). That’s another thing. I feel really lucky to be in this area where there’s Johns Hopkins, NIH, amazing hospitals.

I went there with my scans, told them my whole journey, because I wanted another opinion to see if this is okay. Should I be considering CAR T-cell therapy? Because I had heard about that.

They saw my scans and said, “Technically, you’re clean. I think what they’re doing at Hopkins where you’re on track for a transplant makes sense. If something goes south or something changes, you can come back to us.”

If I even would have called or applied for CAR T or anything else, the CAR T I would have received was already approved for at least a year at that point.

While it was pretty new, it was not a clinical trial, so I didn’t need to go to NIH. I could get it done at another hospital.

R-ICE chemo side effects

It was pretty similar. Nothing markedly different. It was really the same process, where I lost my hair again within 2 weeks or so.

I had nausea. Some people have mouth sores, but I actually didn’t get mouth sores. Going back to R-CHOP, I didn’t have it until the sixth cycle.

For R-ICE, it wasn’t an issue for me, either. It was really just the nausea and fatigue.

What helped with the side effects?

With R-ICE, I was extremely constipated. I did bring it up with my nurses, and they said over-the-counter medicine to treat that would work, MiraLAX I think. Other than that, I didn’t have major issues where I needed to get other medications.

In general, just stay hydrated.

That’s sometimes not a problem because your body’s just begging for water. They tell you to try to drink more to flush everything out because you don’t want all that staying in there.

Also, try to eat. I know that my appetite was not great. I think the worst was when I had the conditioning chemo right before CAR T. That was when I had literally zero appetite.

I was just bedridden. I couldn’t drink; I couldn’t eat anything. My tip there would be just find 1 or 2 things that you can stomach. For me, it’s really weird to say, but it was this fruit juice smoothie that I got from my local organic restaurant, and also cornbread.

Those were the 2 things I could eat. I couldn’t eat anything else. You couldn’t even ask me to eat an egg!

»MORE: Cancer patients share their treatment side effects

What’s it like losing hair a second time?

It was more like, “I’ve been through this before.” My hair hadn’t even grown out that much at that point. It was a boyish style. I was like, “I’d be fine cutting this.”

My mom always said she could cut hair for a living. She cut our hair as children, but those children’s haircuts didn’t count. She was really on board with shaving. She said, “I can do this.” It was pretty easy. I didn’t have to go to a salon and ask them to shave my head because I have cancer.

It was much different the second time around. It was much easier because I knew what to expect. I already didn’t love my hair, so it wasn’t a problem.

Stem Cell Transplant

What tests did you undergo before the stem cell transplant?

At the end of the 4 cycles, I had to start all the tests that they needed to do for the transplant. Before you do a transplant, they have to make sure everything else is okay with you because if anything goes wrong with the transplant, they need to know it wasn’t because of a pre-existing condition or some other issue you had before. They have to know it’s because of this.

I remember going in for a lot. They schedule you as if it’s your full-time job, where you have to go in constantly for a million tests. I think the busiest day was January 31st. That was when I went in for maybe 30 tubes of blood drawn for me. It was a table full of blood. They have to test out literally everything.

I had a lumbar puncture to test if the cancer spread there. I had to test my lungs. I had to get a scan for my brain. I had to test everything. It was really exhausting just to be there all day and have my parents be there as well.

I’m sure it was really hard for them to just sit there and wait for me to do all this stuff. I also had gotten a PET scan, one last one before the transplant.

Getting a stem cell donor match

I found a match at that time. After R-ICE, I had to go through a whole Be the Match thing. I had to get all my friends and say, “Can you please join this registry?” I’m Asian, so it’s really hard for me to find a match.

Luckily, I ended up finding 2 matches. One either dropped out or something, and it didn’t work out. One did confirm.

I went through orientation. You sit in a room where they have a slideshow of going step by step, “This is what to expect,” as if it was my first time with cancer.

They really just want to make sure you know exactly what to expect because a transplant is no joke. You could have serious side effects, short term and long term. I remember being there, experiencing all this.

Second relapse

The next day, I still had some things going on. I had just finished up the lumbar puncture, and I get a call. I’m supposed to meet with the doctor later, but I get a call. The nurses tell me, “Actually, you need to meet with the oncologist now.”

I’m like, “Okay, that’s weird, and that’s not good because I had just gotten the [PET] scan the day before, so it has to be the results from the scan or something. It has to be something.”

I just knew it was bad news. Why else would your oncologist want to see you immediately? If you see your oncologist, usually you’re going to wait an hour or 2. It’s never on time; it’s always going to be late. If it’s early or on time, there’s something wrong.

I ended up seeing him. I was exhausted because I had gotten all these tests. “Please don’t tell me this bad news now.” He told me it came back for a third time. That transplant was cancelled because you have to remain in remission to be going through a transplant. They’re like, “There’s no transplant.”

I’m like “Oh, so all these tests were useless? All the tests were for this very purpose?” I remember just crying. I hadn’t showed any emotion to the oncologist before that. I was just very calm and collected. But at that point, I’m like, “Oh God, a third time? It’s over.” That was devastating.

Deciding on third-line treatment

The plan after that was really just to see another doctor about radiation because they were planning on, “Okay, let’s do aggressive radiation, more chemo, so we can get you back into remission and then do the transplant.”

That plan to me, I’m like, “Are you serious? I just went through all this, and you want me to do more?” I actually hadn’t done radiation before this. Radiation and chemo and a transplant. I’m like, “Oh no.”

At that point, I knew I had to be my own advocate and try to figure out other options.

»MORE: How to be a self-advocate as a patient

Getting another opinion on CAR T-cell therapy

I decided to check out University of Maryland down the street, just consult about CAR T-cell therapy being an option. I had heard about it, and I heard it was an option as a third-line [treatment] if your previous treatments failed. It was still relatively new at that point. It had only been FDA approved for a year. It had been in clinical trials before that.

After that consultation — and they essentially said I was okay for CAR T — I was so relieved. I immediately was like, “We’re going with this. There’s no way I’m going through what they wanted me to do at Hopkins.”

CAR T-Cell Therapy

Describe CART T-cell therapy

CAR T is a whole ‘nother animal because they’re not giving you chemo or radiation, standard treatment that they have for everyone.

They take your cells, something called apheresis. They collect your T-cells and send them to a lab in California. Now I think they’ve opened a lab in the hospital.

At the time, they sent them off to California. They kind of freeze them in a way and then re-engineer them into new T-cells, which are told to essentially find your cancer and attack it.

In terms of the actual process of CAR T, it’s like any blood transfusion, but you have to be admitted because they expect you to stay for at least 7 to 10 days.

They give you back your own cells, except they’re slightly different and essentially an army of T-cells that are going into your body and attacking everything.

The day of CAR T — I say it’s my best and worst day because before CAR T and similar to the transplant, you have to go through pre-conditioning chemo.

You have to give some room for your blood to come back into you so they have to essentially deplete your blood cells and blood. Also, it’s ideal to have as little cancer load as possible from what I heard.

»MORE: Read other CAR T stories

Getting radiation before the new T-cells infusion

I actually ended up getting radiation therapy. It’s what they call bridging chemo, where you’re in limbo. You’re waiting for your next treatment, but you can’t wait that long, so you have to get something else in between.

I had a very light dose of radiation in between having my T-cells collected and waiting for them to come back. That process takes about 2 to 3 weeks.

During those couple of weeks, I was thinking, “This cancer is growing inside me. I don’t want to keep waiting.” It was another moment where I elected to have radiation. I said, “Hey, is there some way or something I can do while I’m waiting?” I ended up getting the light radiation.

Describe the radiation

For a new treatment, you have to do a consult with the doctor. They will prescribe this treatment for you, depending on what you have. I was also thinking about proton radiation, where it’s even more precise. For me, regular radiation was good enough.

You’ll have a couple appointments, but at first they have to draw some marks on you so they knew where exactly to target on the day of. They used a permanent marker to draw on my chest.

You just have to make sure you don’t get it wet. They’ll give you some things, a guard, so when you shower, you can protect it.

You go in to have them get you ready and prepare you mentally, as well as physically. When you go under radiation, my team was incredible. They were super nice to me, and I felt really relaxed and comfortable. You don’t feel anything. You’re just on the bed for maybe a couple minutes, and then you’re done. It’s very simple.

Pre-conditioning chemo

If you take into consideration the fact that they need to give you fluids before, it takes a couple of hours. There were about 2 to 3 days of that.

Then you get 2 rest days. It was during those 2 rest days when I felt so exhausted and drained and couldn’t eat anything. I was in bed for those 2 days.

Describe what happened right before the T-cell infusion

I had a really early morning appointment. I remember waking up, and it was still dark outside. It was cold because it was March. My parents drove me. I got my own room, and as soon as I walked in, I was like, “Okay, let’s get this over with.”

Even when I went to check in before I got to my hospital room, I couldn’t even stand up for more than a couple seconds. I had to hold my mom’s hand and arm and walk.

When you’re admitted, they take a photo of you. I had my hat on. I had my glasses on. They took a photo, and I still have that photo. It’s in my records. I look dead. That’s exactly how I felt.

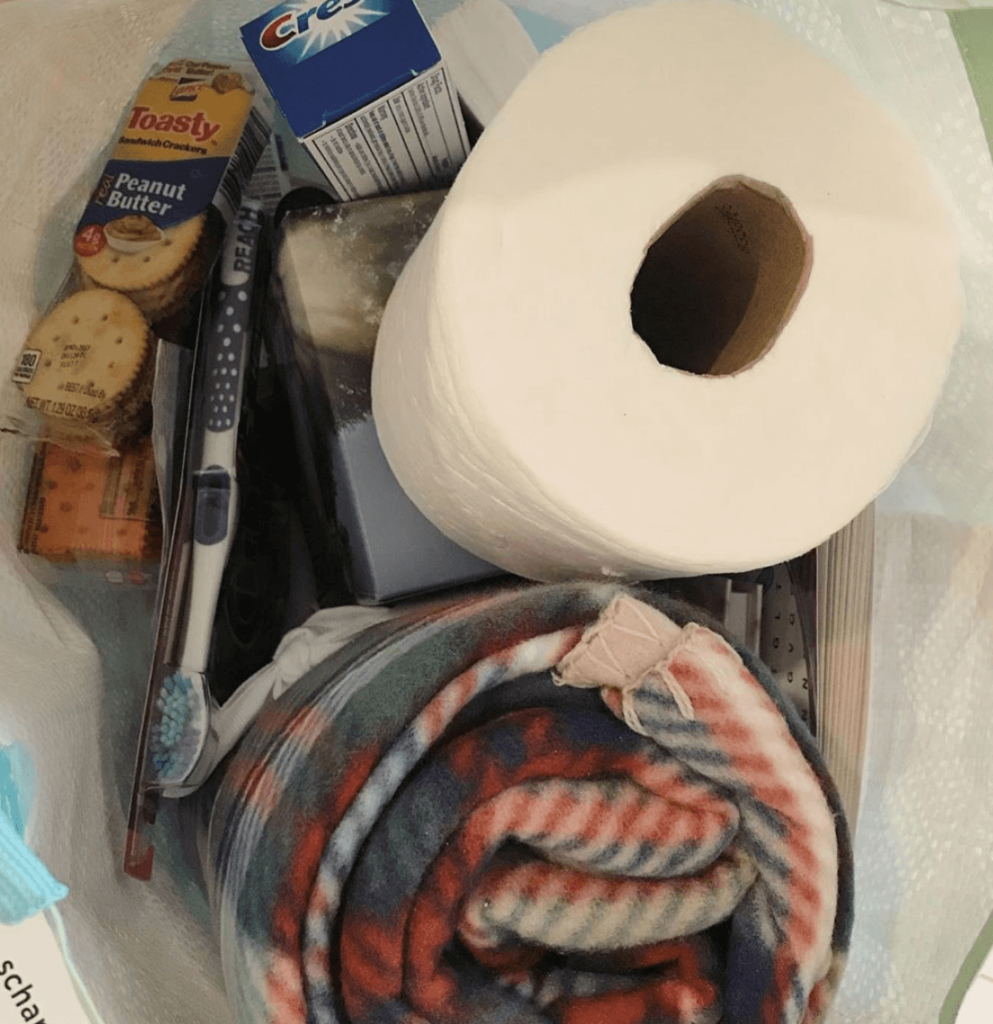

I just walked to the room. The sun was finally starting to rise. It was a pretty good, spacious room. But I saw a bag on my bed, and I was like, “Oh, it looks like a goody bag.” I thought it was from the hospital. Actually ,when I asked the nurses, they said it was from a former patient. I was like, “Wow, so sweet.”

I looked into the bag. It was so special to me. I opened it, and there was a note from a former patient who was in that unit a year prior. It said, ‘Hey, we’re wishing you the best. I’m doing well now a year later.’

There’s a gift card, blankets, toothpaste, all these goodies. Honestly, it didn’t even matter what was inside at that point. That note was more than enough. It was what I needed. It was everything to me at that point.

I latched onto it and was like, “Wow, this is amazing.” I was like, “I’m going to do this. I’m going to steal this idea and do this when I’m out of there.”

It gave me the hope and motivation to keep going. That also gets into what I’m doing now. That gave me so much motivation and inspiration.

Describe the actual CAR T infusion

The CAR T infusion was so uneventful, which is a good thing when it comes to cancer. It was so uneventful. I just sat there on my bed. They give you some candy to suck on because there is a weird taste.

There’s some kind of preservative to keep the blood fresh, which is strange to think about, but there may be some weird taste for some people. I’m sucking on candy, just sitting there. My blood is coming back to me. I’m feeling fine.

There happened to be a student who just decided to join in because CAR T was and still is a very new thing. So they like to have students in whenever possible to witness the whole situation.

Poor her, nothing happened. I’m just sitting there just chatting with her. She was probably my age or younger. It was a really pleasant conversation.

So I think that conversation with the care package, those combined just made me feel like I had a 180. I was a completely different person. I had felt miserable, terrible, dead going in. But the whole process ended up being not as bad as I thought and totally fine.

How long was the infusion

I think it was even less than an hour. It really wasn’t that long. For the rest of the day and the time, it’s just a wait and watch. What will the T-cells do to your body?

After CAR T-Cell Therapy

Recovering from the CAR T infusion

They do tell you to expect a fever after a couple of days and that you may experience some neurological toxicity, meaning you might not recognize who you are, or you might not recognize what’s going on in life because your T-cells are doing their job. They’re attacking not just your cancer cells, but some other cells in your body.

The first 4 or 5 days were like nothing happened. I was just staying in the hospital, feeling fine. I had some side effects from the chemo I received a few days before, but otherwise, I was okay.

What sent you to the ICU?

It was on the night of my birthday. I turned 26. It was midnight. I remember waking up and vomiting multiple times, just feeling terrible. The day or 2 before, I did start having a small fever, but it was manageable still. It was like, “Okay, it’s starting.” I expected this; I knew it.

The fever was getting worse, but it was fine. It was nothing compared to chemo. When it really got serious, it was when I started vomiting, and it just kept coming. They gave me some meds to control it, but the whole experience was just, “Wow, it’s getting serious.” My memory was also starting to go.

All I remember is that they told me, “You’re going to be transferred to the ICU.” Before the infusion, they had said, “You’re most likely going to be in the ICU.”

The things they tell you before to prepare you are terrifying, but at the same time, I’m thankful they told me because I know if I’m going to the ICU, it’s fine. They know how to treat this.

It’s not like I’m in a clinical trial, where I’m going to be in this thing that’s unexpected and they try whatever. They have a standard procedure, where if you have a fever, we’ll give you this. If you have neurological toxicity and you have to go to the ICU, they’re going to give you this.

I ended up staying there for 2 days. I don’t remember most of it because I did have that extreme reaction. Throughout this, they have to test you, so you have to write your name and where you are on a piece of paper every couple of hours. When you’re in the ICU, you have to write it every single hour.

Looking back on my sheet, I remember my sheet was totally a mess. I couldn’t even write beyond “my,” and it was a bunch of scribbles. It was crazy.

Some people have no symptoms, and some people have to stay in the ICU for a couple of days. For me, it was in the middle. It wasn’t a serious reaction, but it was serious enough to go into the ICU. After I was out and back into my room, I was feeling okay again. I felt normal. I was doing a puzzle that my sister had sent me for the rest of the days, and I was just really anxious to get out.

»MORE: Mental and emotional support when leaving the hospital

Recovering at home

I was just relieved at that time because I think any hospital stay is just not really welcome. You usually don’t want to stay in the hospital, especially when your parents are there. My parents rotated their shifts to stay with me. They could not leave me alone, which was a good and a bad thing.

They would bring me home-cooked meals, which was amazing because hospital meals are not that great. I would order them but give them to my dad. My mom would cook the actual meals I would eat, which was really amazing.

I honestly would have lost a lot more weight if it weren’t for her meals because I was hardly doing any activities through my stay. I would maybe take some walks around the ward.

I was in the same ward as the stem cell transplant people, so it’s extremely isolated. This was pre-COVID, and you couldn’t go in and out without wearing a mask. You had to be very careful.

Just being out of the environment was super relieving because I didn’t like to be checked every couple of hours. I had to be given meds every couple of hours. There’s a constant beep of the machine.

The hospital noises are just not very comforting, not a good environment for sleeping or getting any rest. It was really relieving to be back home.

I just remember the couple of weeks after CAR T, I was really exhausted. I was fatigued. I would just stay on my couch and not really do much. I didn’t have any energy, but I didn’t feel any worse than that. I was able to take some walks and get some fresh air, but other than that, I wasn’t able to do much.

How were you feeling before the scan after CAR T?

Mentally, I was just glad I was alive. Whatever happens, happens. I felt good, so I didn’t go in expecting doom. I remember sitting in that room with my parents right before the scan results came back, and the doctor was really busy, but his fellow briefly stopped by to give me a thumbs up or to say it’s good.

I was like, “Oh my God.” We had a mini freak-out before the official confirmation that everything was good. We were just like, “This is amazing!” I remember taking a picture of my parents because they were like, “Thumbs up!”

The oncologist came and officially confirmed it all looks good. That was the biggest relief of my life, especially given everything that had happened.

It felt amazing.

Processing news of no evidence of disease (NED)

I just remember feeling very happy and couldn’t think much more beyond that. That’s great news! I’m not going to think about anything else.

Reflections

Talk about survivorship

Throughout this journey, every little good thing or good news is just an accomplishment in itself. I knew that it still wasn’t over, in a sense. Even still now, it’s not really over because I still have to go back for check-ups all the time. I still have to get scans.

My upcoming one is in a couple of months. It’s never a sure thing. That’s the part about survivorship. People say, “Yeah, it’s kind of like you’re done with treatments, and you’re supposed to go back to real life?”

But the reality is for me, I’m always thinking about it still. Any little pain, any little medical concern, I’m thinking it’s cancer.

I try not to get too depressed or think too deeply into it, but that thought really does come up a lot, especially with my relapses.

If I hadn’t relapsed, if everything went well the first time around, things would look a lot different. I’d be grateful, but not this grateful.

There’s varying degrees of gratitude, and at this point, I don’t even know how much gratitude I can express, but every day is a blessing. It’s ironic and a cheesy cliché, but it’s true. Sometimes I think I can’t believe I’m still here and that I can do what I do. It’s a lot.

How did cancer impact the relationship with your parents?

It drew me closer to them, especially because they really accompanied me to every single appointment. Not only treatments, but the check-ups, scans and everything. They still have their jobs. They’re business owners, so they’re able to be more flexible with their schedules and come with me when they need to.

Especially with my mom, she was the primary caregiver. She had to help flush my Hickman line every single day. She had to cook my meals when I wasn’t able to. She had to make sure that I was staying hydrated, staying in bed. I took her back to taking care of her daughter.

It wasn’t too long ago where she had to be in that role, in terms of me being a kid in high school or something. I had just graduated, and I had only been working for maybe a year or 2 at that point.

She and my dad both hid their emotions really well for me, and so of course, it was hard on them, but they were so strong for me, which I really respect and admire.

It definitely brought us closer together because with any health or life event, this is something that really makes you rethink your values and your priorities in life.

Maybe that minor fight with someone or this minor habit that you’re annoyed with about your mom, that’s nothing compared to what they’ve been doing for you and what we’ve been through together.

Advice for others in getting support during treatment

The main one was transportation. I couldn’t imagine driving myself to and from treatments. That was the main thing.

Being there to take care of me in terms of being fed. There were some days where I couldn’t take care of myself at all.

They had to give me my meals or try to feed me if I could have an appetite. Made sure I was generally okay, not in pain. If I needed anything, they would just be there for me. It’s important to just have someone you know you can call on the phone or down the stairs, “I need you.”

My huge mental support at the time was my boyfriend at the time, now my husband. We were actually long distance. We met in Taiwan. Not during my fellowship in Taiwan, it was the year before that. It weren’t for him and FaceTiming him every single day, I don’t know how I would have gotten through what I did.

Sure, I could call my sister, but she was also technically long distance in Los Angeles. I had friends, and they would reach out to say, “If there’s anything I can do, let me know.” But of course, it’s, “What can I really ask you to do?”

That’s nice of you to say that, and I really appreciate it. I think just having people reach out is better than complete silence, especially from friends who you thought were friends.

There are some people who will definitely ghost you because they just don’t know what to say. Maybe some people have never been affected by cancer in any way, which is amazing, so they just have no idea what to say.

For me, some people reached out, but I didn’t really rely on any friends as much as my boyfriend and parents. They were the ones I could really rely on just for that mental and physical support.

How did you power through the bad news throughout treatment?

It’s always a struggle, even if you have good news. Cancer is just something that enters your life and never goes away. For me, I try to rely on the smallest things to give me happiness or hope.

My sister had just gotten a new dog, so I would ask her to send me photos and videos. I’m a huge dog person, so that was enough for that moment. They also surprised me. After my first relapse, they surprised me by flying over here with their dog.

I remember waking up in bed. I heard some scratching on the door. I’m like, “Oh my God, did my parents buy me a dog?” I opened the door, and the dog comes in and flies and hugs me. It was the most amazing moment.

Just finding the little things that have always given you comfort, just seeing that, but also finding new things.

The new thing that I discovered throughout all of this that mentally gave me a lot of energy and required little energy of me was watching YouTube videos.

Watching mukbangs, which is when people just eat in front of the camera. I never thought I’d be interested in that, but when you have no appetite and you can’t eat yourself, you kind of want to watch other people eating. That’s entertaining, and it requires zero brain energy!

I’m laying in bed watching this and like, “Yes, this is entertaining, and this is enough for me.” Discovering things you never thought would be interesting, like videos, dogs, Instagram, anything.

It was also having my boyfriend there, knowing he was there to talk to me. Our conversations weren’t even about cancer. It was about literally anything else, like his life, things going on in the news or in his family, my family, anything else. Try to distract yourself with as many entertaining things as possible.

I found taking walks was also very helpful, if you’re able to.

I tried to walk with my mom as much as possible. When my boyfriend came, we would try to go for long walks, taking it slow. I’m not trying to go hiking. Just go step by step, day by day.

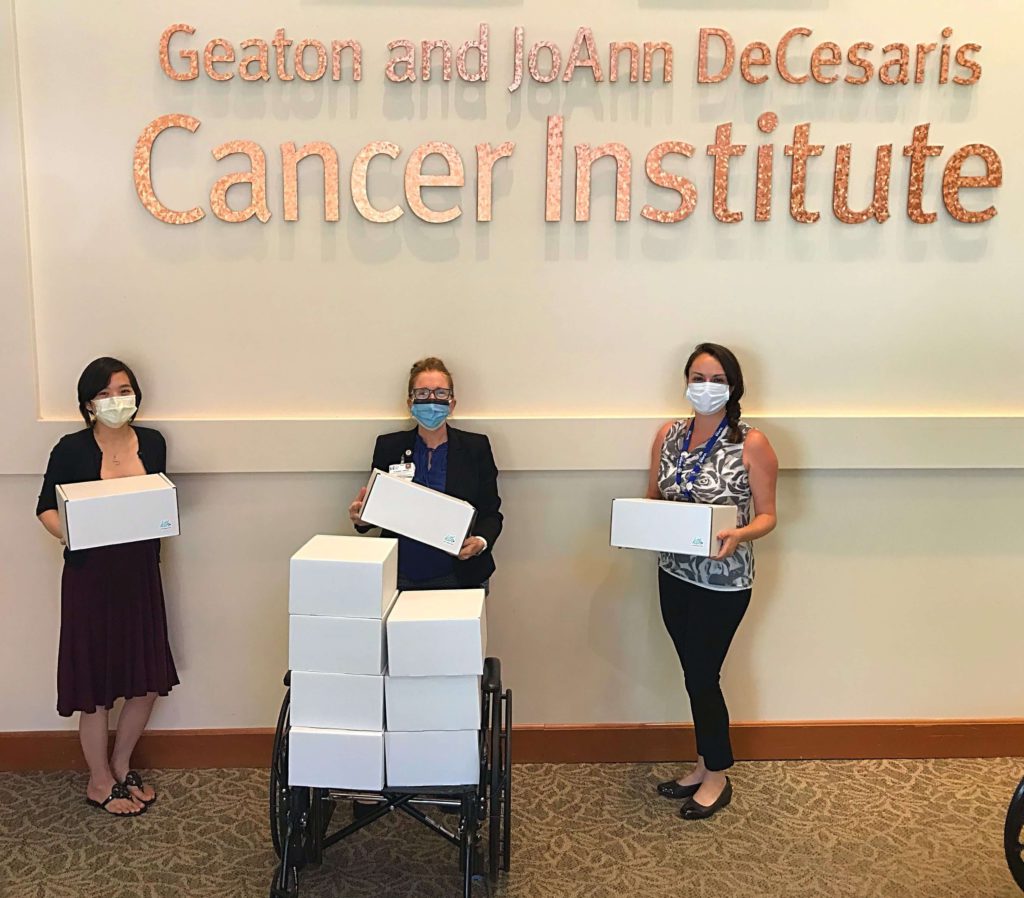

You created a nonprofit to pay it forward

I basically saw that care package and said I needed to pay it forward. It was something that I thought was so kind.

I had to go back to school, though, after I found out I was in remission from CAR T. I was focused on school, and then my last semester was this past spring. I decided to try out some entrepreneurship classes and try to develop this idea, because I wanted it to be more than just an occasional thing, where if I have the time, I’ll come up with the care package to give to the hospital.

I knew this was a need because throughout my years of experience with the hospital, I knew there was so much lacking, especially for young adults like myself and younger people in general. You’re given a binder full of information and expected to read through that, or somehow rely on that for all your information and all your needs.

Nutrition, look at page 75. Flip to that tab. I got so many of those binders, too, because I had met with so many people. I had to go back through all that. They’ll just give you all that information, and it’s not helpful. Not inspiring, not hopeful. But that care package was.

This last semester I decided to speak with a lot of professors and mentors to develop this into what it is now. Now it’s a nonprofit, officially registered. What I’m trying to do is essentially make hospital drop-offs but also ship kits to whomever needs it.

In doing this research and trying to figure out how to make this sustainable, I did consider options of selling these kits, and other companies do sell their kits or similar care packages.

But for me, the idea of selling to cancer patients just rubbed me the wrong way, especially when you have so many other things to worry about. Not everyone can afford even just a $30 kit.

I knew from the beginning I needed to make it accessible, and so now I have these kits where I base it on my own experience, what I needed. I needed lotion with no fragrance because my skin was sensitive, but I also needed sunscreen because chemo affects your skin in other ways, making it sensitive to the sun. Also, lip balm. Just basic things. A reasonable water bottle that would make me want to drink water and keep myself hydrated.

Little things that I knew that were useful for me that I knew I needed to include in this kit. It changes every month, but right now I’m still shipping kits every week. I try to do 2 hospital drop-offs every month. It’s pretty much a full-time thing. I’m sourcing things, speaking with suppliers, speaking with hospitals, doing a lot as a one-person operation.

It’s a lot, but I knew this mission to essentially bring smiles and also solidarity to those affected by cancer is something that’s so important to me because it’s such a lonely journey. You feel you have your friends and family there, but to be honest, nobody’s really going to understand what you’re going through personally.

I wanted to make sure through this kit, I’m able to provide essentials people actually need and also let them know there is hope. I’m here. I went through all this, and I want to let you know I’m here rooting for you. You can do this.

→ Learn more about Kits to Hearts here

Inspired by Sonia's story?

Share your story, too!

Primary Mediastinal B-Cell Lymphoma Stories

Arielle R., Primary Mediastinal (PMBCL)

1st Symptoms: Swollen neck lymph nodes, fever, appetite loss, weight loss, fatigue, night sweats, coughing, itchy skin, trouble breathing

Treatment: R-EPOCH (dose-adjusted) chemotherapy, 6 cycles

Keyla S., Primary Mediastinal (PMBCL), Stage 1

1st Symptoms: Bad cough, slight trouble breathing

Treatment: R-EPOCH (dose-adjusted) chemotherapy, 6 cycles

Donna S., Primary Mediastinal (PMBCL), Stage 1-2

1st Symptoms: Visible lump in center of throat, itchy legs, trouble swallowing

Treatment: R-EPOCH (dose-adjusted) chemotherapy, 6 cycles

Patrick M., Primary Mediastinal (PMBCL), Stage 2

1st Symptoms: Bump pushing up into sternum

Treatment: 6 cycles of DA-EPOCH-R (dose-adjusted) chemotherapy at 100+ hours each

Crystal Z., Primary Mediastinal (PMBCL), Stage 2

1st Symptoms: Chest pain

Treatment: 6 cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy

Stephanie C., Primary Mediastinal (PMBCL), Stage 3

1st Symptoms: Visible swelling around the jaw and neck area, major fatigue

Treatment: R-EPOCH (dose-adjusted) chemotherapy, 6 cycles

Sonia S., Primary Mediastinal (PMBCL), Relapse, CAR T-Cell Therapy

1st Symptoms: Chest pain, superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS); persistent, dry coughs, headaches

Treatment: (1st Line) R-CHOP chemotherapy, 6 cycles (2nd Line) R-ICE Chemotherapy (3rd Line) CAR T-cell therapy

Mags B., Primary Mediastinal (PMBCL), Stage 4

1st Symptoms: Exhaustion, migraines, persistent coughs, swelling and discoloration in left arm

Treatment:(1st Line) R-CHOP chemotherapy, 6 cycles

Stephanie Chuang

Stephanie Chuang, founder of The Patient Story, celebrates five years of being cancer-free. She shares a very personal video diary with the top lessons she learned since the Non-Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosis.

Stephanie V., Primary Mediastinal (PMBCL), Stage 4

1st Symptoms: Asthma/allergy-like symptoms, lungs felt itchy, shortness of breath, persistent coughing

Treatment: Pigtail catheter for pleural drainage, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), R-EPOCH chemotherapy (6 cycles)

Daniella S., Primary Mediastinal B-Cell Lymphoma (PMBCL), Stage 2

Symptoms: Prolonged cough, low-grade fever, night sweats

Treatment: Chemotherapy (R-EPOCH), radiation, CAR T-cell therapy