Montessa’s Small Cell Lung Cancer Story

Montessa shares her small cell lung cancer story that started with a diagnosis at 28 years old. She highlights how she got through treatment, from concurrent chemotherapy and radiation to brain radiation, and recovery.

She also talks about how she navigated life with cancer, being a non-smoker blindsided by the lung cancer diagnosis, how she approached work and time off, finding support in a cancer community, and her lung cancer patient advocacy work. Thank you, Montessa!

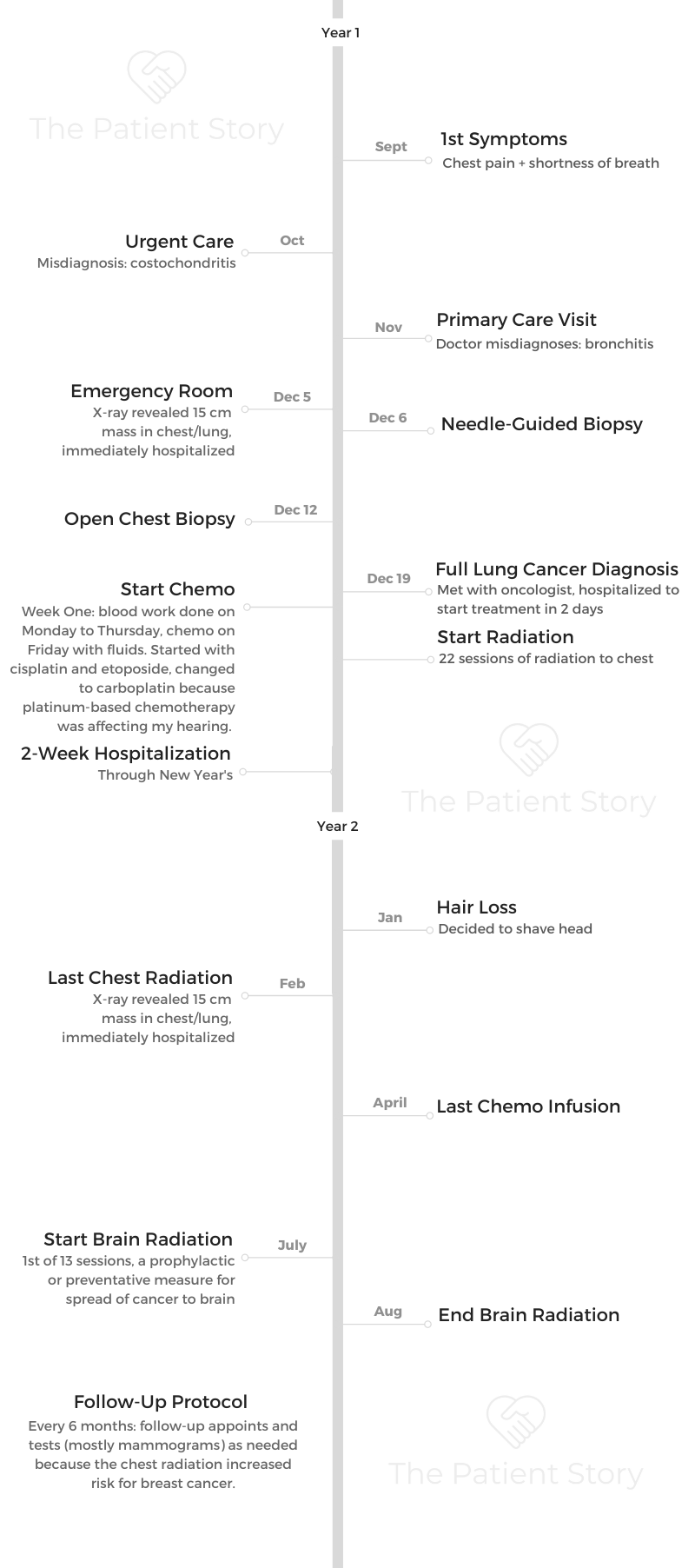

- Name: Montessa L.

- Diagnosis (DX)

- Lung cancer

- Small cell

- 15 cm mass

- Age at DX: 28 years old

- 1st Symptoms

- Chest pain

- Lingering cough

- Treatment

- Concurrent chemotherapy and radiation

- Chemotherapy:

- Cisplatin & etoposide

- Then substituted cisplatin with carboplatin because of side effects

- Radiation: 22 straight days

- Chemotherapy:

- Brain radiation

- 13 sessions

- Concurrent chemotherapy and radiation

- Videos: Montessa's Story

- First Symptoms

- Diagnostic Tests & Procedures

- Lung Cancer Diagnosis

- Treatment Plan

- Chemotherapy & Side Effects

- Describe the chemotherapy treatment regimen

- What were the chemo side effects?

- Self-advocating to get the regimen changed (because of the fatigue)

- What were other side effects?

- Describe the hair loss and how you handled it

- Any tips on dealing with the hair loss?

- It was hot also because of the hot flashes from hormone therapy (Lupron)

- Radiation Therapy

- What was the radiation treatment regimen?

- Describe the actual radiation treatment

- What were the radiation side effects?

- Making treatment decisions

- Describe the plan with brain radiation

- Describe the brain radiation

- Any guidance to others on getting through this type of radiation?

- How did everything look at the end of treatment (final scan)?

- Navigating Life Through Treatment

- Support, Community & Advocacy

- How did you get through treatment?

- Asking for help is tough but necessary

- Importance of self-advocacy

- What are the top updates that small cell lung cancer patients should pay attention to?

- Find your cancer community

- Small cell lung cancer and new treatments

- The trend toward personalized and precision medicine

- The importance of diversity in research and clinical trials

- You see yourself as the ultimate advocate for others

- Small Cell Lung Cancer Stories

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Videos: Montessa’s Story

How I Got Diagnosed

Treatment: Chemotherapy & Radiation

Navigating Life with Cancer

First Symptoms

Tell us about yourself outside of cancer

I appreciate that we can’t be defined by a box. Beyond patient advocacy, I’m a mentor teacher. Specifically, I work with novice teachers.

My background is a special educator. I have a master’s in autism and inclusion. I really prefer working in populations in our schools that have autism or any teacher who is working with a large group of children with special needs.

I do work for that, and I’ve turned some of the advocacy work I’ve learned from lung cancer into education. I am currently a doctoral student as well. With all of these things, I don’t know how I could keep my calendar and my mind managed!

What were your first symptoms?

I had chest pain, a cough. I remember because it was a day in September where we were having a going-away party. I have a friend in the military, in the Navy, and she was going to be stationed away.

That’s probably why that date and month stick in my head.

I went to the urgent care clinic. They poked around and said, “Oh, you have costochondritis, inflammation around the rib cage.”

It sounded legitimate because I had been working out that summer pulling weights. I don’t know, you trust the medical professionals.

They gave me Motrin, and I went on about my business. Then I developed a cough that wouldn’t go away. A lingering cough. The chest pain was still there.

Describe the first doctor’s visit

I went to a primary care doctor. This was a new doctor. I had never seen this doctor before going to meet her. They said, “Oh, you have bronchitis.” Never gave me an X-ray.

At the time, I was 28 years old. I didn’t know I was supposed to have an X-ray for bronchitis. I work in a school system with kids. I was like, “Sounds legitimate. Maybe the kids get sick. Maybe I just got sick.”

Then she said, “You have a whopping heart murmur. Anybody tell you that?” I was like, “No, nobody has ever told me this in my life, that I had a heart murmur.”

She was keen to the heart murmur. She sent me to go get an echocardiogram, but never gave me an X-ray and sent me home with an inhaler and antibiotics. November, I remember driving home.

I had back pain. I would have back pain throughout. Even my teachers I was working with would later tell me that I would complain about back pain, but I didn’t connect the two.

Trip to the emergency room (ER)

By the first week in December, I was in grad school for my master’s. The pain came back. I lived with my cousin at the time. I called her and said, “The chest pain came back. You have to take me to the ER.”

She’s like, “Oh no.” She had told me, too, that the cough was still there even after I had finished the antibiotics. I said, “Oh, I made another appointment. Maybe it just lingers. I don’t know how bronchitis works.”

She said, “Shouldn’t that cough be gone?” Red flags are coming out. I went to the ER at the regular hospital this time. I was in so much pain.

Ironically, by the time I got home from the grad square, I’m like “Oh, I have to take a test.” I have no idea even how I made it through the test because I was really in pain.

The pain had subsided, and I wanted to eat something. I was not worried. I said, “Maybe the ER can give me some medicine, so go ahead and take me to the ER.”

She took me, and they immediately hospitalized me after realizing my oxygen level was like 83 or 85.

They did an X-ray and said, ‘We found a mass, and we’re keeping you.’

All I heard was ‘IV,’ which meant needle in my head, and ‘biopsy,’ which meant surgery. I was like, ‘I have to go to work in the morning. No, I can’t stay here.’

I’m sitting in the bed, if you could imagine, sitting in the chair. My cousin’s standing above me, [saying], “They found a mass in your lung. You’re sick.” I’m like, “No.”

In my head, I’m thinking somehow I’m functioning, I’m walking around. I can’t afford these bills. I’m a teacher. Not knowing, the fear of the unknown. Right now, it’s all questions.

They said, “Do you want to see the X-ray?” I said, “Let me see.” I had no idea what I was going to see, but the way I describe it to people is if you have no knowledge of what your lungs are supposed to look like, if you look up in a dark sky with some binoculars, you’ll see dark lobes and maybe some white lines.

Imagine someone taking a paper towel, balling it up, and covering one of those lenses. Three-fourths of my lung on the left side was not visible. Only one-fourth was visible. That’s how large a 15-centimeter mass was by the time they found it.

Processing the gravity of the situation

I looked to my cousin and said, “Oh, I guess I’m staying.” I still had no idea. At that time, they were just whispering things like, “Oh, is it possibly cancer? Possibly not. We don’t know. We’re still going to do some tests.”

Actually, they said they were going to do all this before I saw the scan. Then it made sense. I understood. I visualized in my mind what the mass was that they were talking about.

Things started becoming clear, like why I was having trouble sleeping. Before, I thought it was my pillow [and] everything else.

Describe your mindset as a 28-year old non-smoker facing this diagnosis

My normal temperament would have been pessimistic, like, “Oh, well, it’s me.” Go into a hypochondriac mode.

That’s where my faith comes in and part of the book that I ended up writing.

I heard a voice of life whisper to me and say, ‘This is going to be bad, but it’s not going to kill you. It’s going to be a healing testimony for someone beyond yourself.’

I didn’t know at the time whose story this was for or what journey I was going to go down, but I had to hear that because my normal temperament would have been, “Let me lie on the bed.” I would have been a worrywart, a “negative Nancy,” the whole way through the journey.

Everything happened rapidly. I didn’t have time to process, especially when you’re sick like that. They did immediately hospitalize me.

Diagnostic Tests & Procedures

Describe the needle-guided biopsy

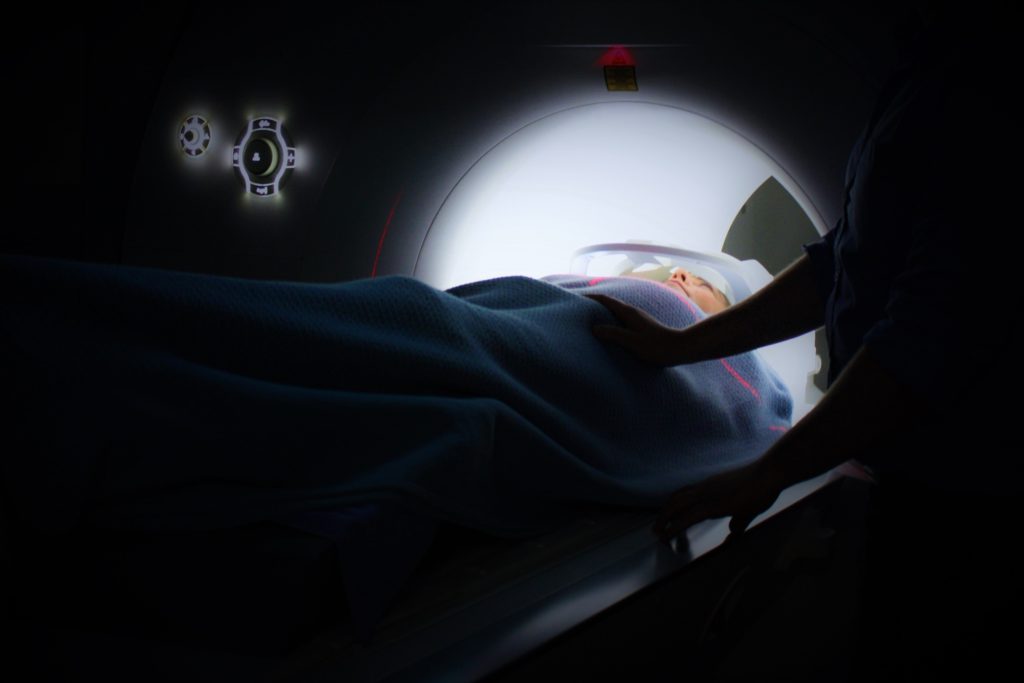

That was the first time I was hospitalized. They did the needle-guided biopsies, where you sit on something like a CT scan or ultrasound. They can visually look at where they’re doing the biopsy. They get a syringe or a needle and take out the tissue. I believe I was awake. It was not as invasive.

I got a call back probably at the end of that week, and they said, “Hey, we didn’t get enough tissue sample. You have to come back in for an open chest biopsy.”

The doctors and surgeons were going back and forth, I think because of the theory of cell spreading. I didn’t know all the science behind what they were explaining at the time. I went back probably a week later.

Dealing with such a large mass

The surgeon at the time was trying to connect me with an oncologist. My cousin, who worked at another hospital, was actually on the call the whole time because he didn’t believe it the first time I was in the hospital with 15-centimeter mass.

He told me, “You must be mistaken. It is not a 15-centimeter mass.” I still had no idea that it was huge. Even though I saw it, I didn’t know it was abnormally huge. I just said, “Okay, it’s the size of a cantaloupe.”

The doctors were very calm telling me these things — until I went later on, and people I met in patient advocacy were like, ‘That was humongous!’

I was the talk of the water cooler probably because everybody would come in and say, “Was anything lighting up? Did you visibly show anything?” That was probably the medical student there.

Describe the open chest biopsy

I did break down and cry that time. I don’t know why they tell patients some things, but they’re like, “We can’t fully sedate you.” In my mind, I was thinking I was going to be awake.

It had something more to do with the intubation or something. They couldn’t do something because of me lying down flat on my back. I wouldn’t have been able to breathe, but I still was out enough that I do not remember anything.

Lung Cancer Diagnosis

What do you remember from getting the diagnosis?

It wasn’t until I met my oncologist that I got the diagnosis, even though they probably knew about the cancer because the surgeon was trying to connect me with an oncologist. I didn’t get the diagnosis until I met my oncologist that next week. The doctor was very, very calm.

I have a large family here. Before my mom came up from North Carolina, my extended family was driving me back and forth. A male cousin and I were in the office, and the oncologist said, “It’s a really stupid name. We used to call it oat cell cancer because it looks like oats in the microscope. Now, it’s small cell lung cancer.”

My cousin and I looked at each other, laughed, and said, “That is a dumb name.” He said, “We’re going to hospitalize you and start X, Y, Z.”

I asked if he could give me one more day because my mom and my aunt were coming in soon. I asked for one day before I had to go back to the hospital.

I don’t know if he willingly did it, but he caved in and let me wait one day until they arrived. I can’t remember the exact day, but it was one day in between. He let me wait, and then immediately I was back in the hospital again.

What were the details of your lung cancer diagnosis?

I started looking up what “small cell” was. I had no reference. My grandfather had died of lung cancer, but I still had really no reference of how deadly the disease was, especially the difference between small cell and non-small cell. I think the paper said “advanced.” It might’ve said “extensive,” because usually it’s extensive or limited.

I know I had limited, but I don’t know if the doctor put “extensive” on there as a call to speed up the process of things or because the tumor was so large at the time. They thought it was in the lung. By the time they found it, it was in the mediastinum area, but it had not metastasized.

I looked at it, thinking, “How could this be right?” Because again, my body wasn’t functioning at 100% by any means, but I was going day-to-day at work, and then immediately, everything stopped.

How did you process how the cancer would impact your life?

Looking back, I couldn’t wrap my head around it.

I took what he said and heard, “You’re going to start chemo. Your hair might fall out, might not. My patients usually don’t get nauseous because I give them X, Y, Z medications.”

I remember him talking about the type of chemo I was on would impact my kidneys and that I should drink a lot of water. I’m surprised I could remember all this, but he was telling me all of these things.

Describe the radiation treatment plan

My oncologist did say we’d start radiation, but the radiation oncologist talked more about that treatment side. I think he said after 6 or 8 cycles of chemo, we would start radiation.

Actually, they started a PICC line first, before I had another surgery, to start the first dose of chemotherapy when I was hospitalized.

»MORE: Read patient PICC line experiences

I didn’t know about some of these other issues, like I had fluid around my heart. I ended up getting a pericardial window when I was hospitalized at that time. They put a mediport in.

I don’t even remember him telling me if I was getting a mediport, but it was the best thing that could have happened when they did that surgery as well, to also put the mediport in.

I was there longer than they thought because the fluid wouldn’t drain off from that pericardial window. I remember him coming in because it was around Christmastime, too, so he was on vacation for some of that time. There were your physician assistants and others coming in during that time.

How did you break the news to loved ones?

That’s a good question, because I don’t even know if I called anyone to tell them. My cousin who was with me at the time, who lived with me, called the doctor. She also called my aunt, and she told her to call my cousin Keith, who’s an interventional radiologist at the hospital, and get us connected.

We got on the ball, and Keith also called over to the hospital to talk to the doctors to get the doctor language and get what was going on. My cousin called my parents and said I was in the hospital. They called another aunt. The chain got passed through.

My dad would always say, “Tell Montessa. Telephone or telegraph. Tell Montessa; it’ll get around.” I lived with some of my close friends from work, so one of them called the others, and they connected with my principal [manager at work]. Three of my really good friends from work ended up coming to the hospital that night.

»MORE: Breaking the news of a diagnosis to loved ones

Did you get a second opinion?

I was very happy with my oncologist. I trusted my family, so I went with him.

But I think people need to get second opinions. I’ve met several people now, all these years later, who all needed to get a second opinion. I have a friend now dealing with a different type of cancer who got a second opinion, because she didn’t want this radical surgery that they had recommended at first.

We patients have to be educated.

All they can do is tell you no or yes if you go get the second opinion. I didn’t go to one — I won’t name the hospital or treatment center — because I had a coworker who said they treated her husband like a specimen or a research project.

They weren’t looking at a holistic approach, and I needed somebody a little bit more personable. I just wanted to stick with my oncologist.

Treatment Plan

Describe the start of treatment (chemo, surgery, radiation)

Originally, because they wanted to start the chemo right away, they started a PICC line.

I won’t forget this either, even though I do say sometimes chemo has affected some of my memory, but they put the PICC line in.

I remember it wasn’t pointed in the right direction. They had to go back down to interventional radiology to get pointed in the right direction, and these things in my mind when they’re like, “We can’t get it.”

Again, I don’t know why they tell patients all these things, but they were like, “If we can’t get it to work through your arm through here, we have to go up through your thigh or something.” I’m like, “Oh no,” but they got it working and started the chemo right away.

I must have had the surgery after that first round. They put the mediport in and did that pericardial window. I started radiation when I was hospitalized as well.

The important role nurses play

I remember one of the nurses saying, “I want it to be there to start the chemo,” which was quite interesting. It shows you that personality and the bedside manner of the nurses. They started the chemo then.

You had to travel between different treatment centers

There was a different little caveat because when I was released from the hospital, my oncologist had me go to an infusion center at another hospital, but the radiation oncologist was at the original hospital. I’ll say hospital A and B. I would have to get picked up, and the church arranged rides for me.

This was just miraculous. They arranged rides for me to be picked up at my house and took me to radiation treatment. Somebody picked me up from the radiation hospital A and took me to B to get the chemotherapy on the days that I had both radiation and chemo.

Chemotherapy & Side Effects

Describe the chemotherapy treatment regimen

The chemo would be cycles of like 3. Week 1, I’d have blood work done on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday. Then I’d get chemo Friday.

I’d get fluids. They started with cisplatin and etoposide. Eventually, I had to change to carboplatin because I had ringing in my ears. The platinum-based chemotherapy was affecting my hearing.

Somebody would pick me up [and] take me to the hospital every 3 weeks. That week it would be chemo week, and my mom would come up from North Carolina [on] those weekends when I had chemo treatment. Then I would have another week of blood work. It was always blood work, then chemo week.

What were the chemo side effects?

Every 3 weeks, I’d have these chemo weeks. Then it got to April. I was so fatigued that the doctor had to change the regimen a little bit. I had to take a week off of the chemotherapy treatment.

That type of fatigue, I can’t even describe it. Even to walk from my apartment around the corner to a neighbor’s apartment took every bit of energy that I couldn’t muster up.

»MORE: Cancer patients share their treatment side effects

Self-advocating to get the regimen changed (because of the fatigue)

Yes, because in my mind, I didn’t think that my oncologist was going to do anything. I give him credit, too, because from my other little advocacy groups I’ve been a part of, sometimes they say that the doctors don’t even ask them as a whole picture of, “How are you doing? Are you having any insurance problems, money problems? What are your issues? How are you?” Not just the treatment of the disease but, “How are you?”

I just told my oncologist, “Hey, I’m so worn out, very fatigued.” That week (off) actually made a difference. It helped.

What were other side effects?

Like my oncologist stated at the very beginning, a few of his patients get nauseated. I think he tries to get out ahead of that and have patients handle the nausea. He said, “You should drink water.”

The days I was nauseated were the simultaneous days of radiation and chemo. I would go to chemo those next mornings, and I would feel a little queasy. Those mornings, I tried to drink water and tried to stay hydrated.

Describe the hair loss and how you handled it

The hair fell out after I got out of the hospital, and my mom helped me comb my hair. Like a little office trash can — my hair at the time, I had an Afro, and so all of my hair completely filled that trash can, just coming out in clumps. I had little sprigs of hair. I went to my hairdresser and just got it shaved off, and it was bald.

I had come to the resolution before that I wasn’t going to wear a wig, because it was too hot for me. I didn’t know what my head was going to look like underneath, but I just resolved to the fact that I would be bald.

»MORE: Patients describe dealing with hair loss during cancer treatment

Any tips on dealing with the hair loss?

Yes, I just went through this with my friend who was just recently diagnosed with uterine cancer. When an oncologist tells you, “You could lose your hair. It could not. Maybe it’s going to stay in.” Right then is when I decided, “I’m going to get some hats, or I wear some scarves. I’m not going to wear a wig.” In my head, I had already decided.

I didn’t know what my head was going to look like. I still didn’t know for sure what was going to happen. I didn’t know what that process of losing my hair was going to look like.

My scalp became tender, and it hurt when my hair fell out. Who knew?

My hair was braided when I was in the hospital. Then coming back out and having that Afro, the hair was just coming out in clumps. When the hair was scraggly on my head, I said I looked like a cancer patient.

That’s very stereotypical, but my hair looked like little sprigs coming out of it. I said, “It’s better just to get it clean shaven, and maybe it’ll grow back even.”

My mom was there with me at the time. We went over to the hairdresser, and I remember her closing the door to give me some privacy. The hairdresser just cut it off.

Wigs are beautiful. Now I see a lot of very stylish ones. I just didn’t want it because it was so hot. It would feel like it was hot on my head, but you’ll see in some of my other advocacy pictures, I used to wear a wig to chemo, sometimes Afro wigs, and I acted like that was my hair again!

It was hot also because of the hot flashes from hormone therapy (Lupron)

I did have hot flashes. I remember joking with my coworker at the time. She was older, and she would always have a fan on. “It’s always so cold in here.” “Don’t turn this fan off.”

Then I said, “I know what you’re going through now because having these hot flash attacks now, I can’t joke with you anymore.” It’s like, “Now I understand. Now I can walk in your shoes. I understand why you have the little fan on.”

Radiation Therapy

What was the radiation treatment regimen?

The radiation oncologist explained it was going to be 22 days straight of chest radiation. They were going to resize and re-image the area.

They wouldn’t be radiating good tissue, because with small cell lung cancer, it usually responds well to that first round of treatment, but it tends to come back. The goal was, of course, to shrink that tumor with simultaneous radiation and chemo at the same time, so they explained.

Describe the actual radiation treatment

For the radiation treatment, it was very painful initially to lie down flat. It was extremely painful. It was so hard to breathe that I would cough.

All of these tests — MRIs, CAT scans, the radiation treatment — you had to lie down flat. I had to come up with a systematic way of lying there. I closed my eyes, and the machine moved over me.

I would count how many times it moved to know how close the treatment was to being over. I’m counting, like, “One, two,” in my head. I visualized how many times I had to move and get up from the radiation treatment.

What were the radiation side effects?

One of the side effects was I got a dark patch on the circle of my front and back from where the radiation was. They tell you some products to use beforehand, like Aquaphor. I started using some of those not during the treatment, but after. You could put the Aquaphor on to treat those scars.

I still have scars even from the surgery that I call my battle wounds. It took a long time for the dark patch to fade, the dark patch from the front and back.

It’s just something you notice after the fact. I don’t think I noticed it during treatment. You just look down one day, like, “Wow, look at that dark treatment.”

It was also so painful even to swallow saliva at one point from that treatment. I don’t know what made the pain go away. I don’t know if it’s just as they re-image the area that I can remember lying on the sofa, and it just being indescribable pain to just swallow saliva from that radiation treatment.

You don’t know what side effects are coming from what, because I was doing both radiation and chemotherapy at the same time. My red blood cell counts were down.

I had to take shots for that. With chemo, I got a shot to boost the white blood cell counts. You just have simultaneous side effects that you can’t pinpoint what comes from what.

Making treatment decisions

Chemo ended in April. Then in June or July, I remember the research coming out, because by then I was reading everything about prophylactic cranial brain radiation. This is the time I thought I would be able to navigate my choices.

During chemo, I had met a lot of cancer patients, mostly breast cancer patients. I met somebody with stomach cancer. They would tell their stories, like, “Oh, well, no, I got surgery, and then I didn’t have to do this.” My church had a cancer ministry. I’m meeting people, like, “Yes, I chose not to do X, Y, Z.” I was like, “You had choices?”

Like, “Wow, you got to choose.” When this news started to break in my head, I was like, “Okay, now I’m going to have choices. I’m going to have options.” I thought I could ask my oncologist, “Basically, can I choose not to do this and choose to do this?”

I went in, and I knew what the radiation oncologist was going to say. I was like, “Can I have an option?” I’m going to ask the radiation oncologist, “Would you get brain radiation done?” She’s like, “Yes.”

Describe the plan with brain radiation

Sometimes lung cancer will spread to the brain, this primary place, so this was a prophylactic. The radiation was to prevent the cancer from spreading to the brain. I’m sure they had been doing studies before, but I was just reading the research around the time I was sick.

Even after that treatment, I remember then going back to the surgeon because part of the mass was still there, though it wasn’t active.

There were no signs of cancer, but they thought it was the scar tissue. The tumor was just folding in on itself, but they couldn’t do surgery because the remaining mass was on my pulmonary vein. If they cut that, I could die on the operating table.

That was probably the most devastating for me, to go through all that, get to it, and not be able to take the rest of the tumor out. That was probably not the only one, but one of the breaking points, when they said, ‘Oh, no, we can’t do that surgery.’

Describe the brain radiation

It was 13 days of brain radiation that I had. That process was very different than the chest radiation, because it looked like a mesh-like mask. They conform it to your face, and they tack it down to the table. This mask is over you.

I decided to keep the mask after treatment because I said, “Every year, I’m a cancer survivor.” Even though I never followed through, I was like, “I’m going to put a sticker on this mask every year,” like a cancer-versary.

Any guidance to others on getting through this type of radiation?

I closed my eyes and tried to count how many times that machine moved. If you are claustrophobic or you don’t like anything over your face, just try to breathe in or do some breathing exercises. Keep your eyes closed during that treatment when they put the mask over you.

Now there’s so much technology, even the CyberKnife, on how they can do it. Then the key is to lie as still as possible. Don’t move, and it will be over quickly. That was my ammo throughout all of those sessions, to just lie there, get it over with, and count how many times the machine moved before I could get out of there.

How did everything look at the end of treatment (final scan)?

My whole scalp, the top of it was dark. It was odd because I had hair here, the nape of my neck, so it looked like a mullet with no hair on the top. I had to get that cleared up [and] cut them in back, too.

It was interesting that the hair grew there, and I guess that’s the part where the brain radiation was, the cranial part up here. I would get some type of ointment for my head to my scalp.

I was still bald, but until looking at the pictures, I didn’t realize how dark my scalp was. It was a two-tone for my head.

I was hospitalized in January or late in December. That’s when I started the radiation. By March, the scan started coming back clear. The PET scans showed there was no evidence of the disease.

The chemo cycle still continued until the end of April. I believe it was every 4 months to get a scan, and then it went to every 6 months. Before I turned 35, they were like, “When you turn 35, you have to go get regular mammograms, because the radiation to your chest put you at risk for breast cancer.”

In my head, I’m like, “I remember signing my life away, but I don’t remember reading that specific side effect.”

Navigating Life Through Treatment

Were you able to drive yourself to the appointments?

The brain radiation, during the chemo, somebody drove me to all of those because some of the medications I was on also made me very drowsy. I couldn’t really drive and be loopy. Some of those pain medications made me out of it. The church organized those rides to pick me up.

I would drive myself to go get the blood work on the weeks I didn’t have the chemo, because I wasn’t on the pain medications the whole time. The anti-nausea medications made me drowsy, too, so they drove me to those.

I remember the last day of my brain radiation was my first day back at work. I’d missed a whole half of the school year. The kids weren’t there yet, but it was the pre-work for the teachers. I went in and left to go get my last brain radiation treatment.

I came in that morning for check-in and did half a day, then left to go get the brain radiation treatment. I’m like, “Look, I’m tired of sitting here.”

Do you wish you had taken more time off?

I probably took the right amount of time off, because it was good to have a clear start. Originally, I was supposed to go back in May. I would have missed months and come back almost mid-school year, trying to wrap up. It was a clean break to start back.

I was strategic about the time I still had to take off because I was going back every couple of months for checkups and more scans. I remember even my aunt working it out one time I had to get a bone scan.

I went to work. Somebody picked me up from work [and] took me to the hospital to get injected with that substance they inject you with for a bone scan. Some radioactive stuff. [I] went to go get injected, and you have to wait a couple of hours.

They brought me back to work, finished the day out, [and] went back to the hospital to get scanned. I think I had no leave, so I had to strategically work things out.

Any guidance for others on how to approach work?

This is a good conversation. Really, I just went through this with my coworker, and I was telling her, “If you have to take time off…” We have a sick bank leave, and you have to go fill out the paperwork with our union or bargaining agreement.

The stigma of “not looking sick”

This is a stigma with cancer. Sometimes people say, “You don’t look sick.” I said, “I’m going to be walking in here (during treatment),” and they’re like, “She’s walking. How can she not work?”

I was young, and she said, “Who cares? Your doctor has written this note for you, and it says you can’t work.” Looking back, I know there’s no way I could’ve worked.

At that time, I didn’t envision how much I was going to be going back and forth to the doctor and how long these chemo sessions were. Actually, I was in there 6 hours all the time.

You don’t realize you can only focus on yourself. You can’t focus on work right now. You can’t do that. It’s not plausible because still it was a whole shift at work. Now you’re in a different life.

Any guidance on how to deal with the PICC line?

You can relate it like an IV. It’s not going to be in there permanently, and it’s in a better position because it was in my upper arm. It wasn’t right here at the bending part of the arm.

You’re awake when they do the procedure, so it’s not invasive. I don’t know if they do it for people if they’re outpatient, but we know it was fine because I was already in the hospital, and they could maneuver it or treat it right there.

»MORE: Read patient PICC line experiences

There are products that help with quality of life with things like PICC lines

I just came from my checkup at the Cancer Treatment Center, and they’re putting a covering in there. They had started an IV, and I’m like, “Those are much better.” I knew band-aids used to tear my skin, so that new bandage they have that they can wrap around you is really good.

You don’t think about these little things. I can remember peeling off the coverings very slowly. Some of those bandages, you hold your breath and pull it off.

Support, Community & Advocacy

How did you get through treatment?

It’s important that something else I had to learn was swallow your pride, and don’t be afraid to ask for help.

Like that day when I was fatigued and having to go walk to my neighbor’s apartment, I had already had a ride scheduled.

Our church was having a big event that happened to be that week that I would end up having chemo. I had to go ask my neighbor for a ride. Just swallowed my pride to say, “Hey, I need help. I can’t do this on my own.” I had friends who supported me, my family, extended family, and the church family as well. Their help was a big part of it.

Then finding something to do, like a hobby. I remember doing some arts and crafts when I first was diagnosed, before I knew how long I was going to be home for.

Now everybody knows what it’s like from being in this pandemic, but being home when you’re used to being out, or out and on the go all the time, isn’t easy. Find things to do and pick up hobbies. Read books. I read a lot of books and picked up different hobbies. I actually picked up painting now.

Just finding things to have an outlet. I was using a lot of Google, but that might not always be a good thing. You probably have to have your time limit of what you read on the internet as far as medical concerns.

Asking for help is tough but necessary

Yes, and it’s hard to realize, especially if you’re young. Even if you’re an older, independent person, and you go to, “Wow, I can’t drive. I’m too loopy; I can’t drive. My mind is too drowsy. I can’t do it,” or, “I’m not feeling well, I need help. I need somebody to bring me some groceries or food.”

Things you don’t think about, just the care of people. You really find out who your friends are, too. Also understanding what some people can deal with.

One of my brothers didn’t want to see me bald, or he didn’t want to see me in that state. He wanted to visualize me as he knew me before the sickness. That’s the picture he wanted to maintain in his mind.

Importance of self-advocacy

You can’t be afraid to be a self-advocate for yourself. That means asking questions, and if you don’t know the questions to ask, have somebody there with you. I met a couple recently, and the wife was too emotionally distraught, so I told her husband, “You’re going to have to be the one to ask these questions now.”

Because I’ve been doing lung cancer advocacy, I was able to give them some questions. This picture is my mom and my sister with me as a celebration of life when I started getting treated at cancer treatment center. There they are, and this is a fight.

I think I don’t know if people realize that cancer is a journey, but it’s also a fight. You put your boxing gloves up and fight whatever comes at you. Imagine a boxing bag in front of me, kickboxing bag or whatever, and punching it down. Yes, so lung cancer can’t defeat you.

There’s a famous poem about that, what cancer cannot do. It doesn’t define you. I’m not just a cancer patient; I’m so much more than that.

What are the top updates that small cell lung cancer patients should pay attention to?

I think it depends on what your focus is when you come out. At the time in 2006 when I started reading all that information, of course, it was bad.

I saw that the bridge had not been moved in the way we treated lung cancer patients, period, non-small cell or small cell.

I was angry, and I turned that anger into advocacy and having a voice. I saw when I got into that advocacy work. I would go to these conferences. Then I saw that there were a lot of things for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In the last 5 years or so, there have been a lot of advancements for non-small cell lung cancer.

If you turn on your TV, you could see a Keytruda drug announcement or other commercials and advertisements for lung cancer treatment options for non-small cell lung cancer, specifically for immunotherapy. We were waiting.

We want to focus on small cell lung cancer [and] say, “Okay, look, some drugs and some of these treatments, we’re not going to be the Cinderella step trial of lung cancer. Let’s get this out here.” I started to realize that there weren’t many of us who have small cell lung cancer who are still surviving.

So we wanted to give that voice. Some of the other advocates are like, ‘Let’s show them survivorship. Let’s show them hope.’

I want people to know that if your doctor tells you, “Go home and get your affairs in order,” which is what I was hearing from some patients in 2006. Matter of fact, I just heard it from somebody. He didn’t have lung cancer; he had another cancer. They told him the same thing.

I’m like, “No.” I said, “Your doctors aren’t God. Nobody knows.” Sometimes I think your mental state can help you through that survival, [as well as] who you surround yourself with.

Find your cancer community

If you get involved in some of these groups that have the same cancers you have, you can hear stories.

- How did I get through the hair loss?

- How did I get through the neuropathy?

- How did I get through this?

- What stories did I read?

You have somebody who’s walking through the journey with you. Your family is fine. They’re there. They have their own journey being caregivers, but somebody who is walking that journey with you, or has walked it, I think it’s very important that we get connected.

I guess ‘connected’ is a keyword. Just like when I had to swallow my pride, you need to get connected with people or a network of people.

I know some people don’t want to do that. They want to keep it private to themselves, but I think you have to find someone, even if you go to a therapist. Therapy is not bad to get someone to talk to. Keep your whole person — mentally, spiritually, physically — whole and healthy.

Small cell lung cancer and new treatments

We are on the verge of something. You cannot imagine how many times I’ve been contacted in the last couple of months. I think it was in 2019 that Tecentriq was made from Genentech, an immunotherapy drug for small cell lung cancer.

Now the dates are blurred together, but I’m glad that this is what I’ve been waiting for it and seeing we are on the cusp of saying options, being plural, as treatment options for small cell lung cancer.

I just can’t wait to see that there’s going to be X number of genetic biomarkers for small cell lung cancer, so we can have targeted treatment. How did we know?

I had faith and I heard that word, too, but how do we identify these other patients who might be 12 years down the road with the regular treatment option that hasn’t changed in 30 years, versus the people that will work with this immunotherapy drug?

I hope they have hope. There’s a new group of small cell lung cancer patients who bring a voice to the advocacy as well, who had an EGFR mutation that then transformed over to small cell lung cancer.

At one point, a researcher told me that even the tissue samples weren’t around to go look at my tissue samples and have them re-examined to see if by chance I have an EGFR mutation. It transformed, but by then the tissue samples weren’t around.

The trend toward personalized and precision medicine

I don’t know if they’ll automatically do it for small cell lung cancer, but I think we’re on the cusp of that happening. We have a stigma in the lung cancer community, as it’s associated with smoking.

Now things are changing, though much of the focus has been on non-small cell lung cancer. Of course, we are the smaller percentage of people, but 10% of the people have small cell lung cancer. That’s still a lot. That’s still a lot of people who will be diagnosed with small cell lung cancer.

The importance of diversity in research and clinical trials

I want more African Americans to get involved. My passion for advocacy and the focus areas have shifted some, even starting with me wanting to get the voice out that young people could get lung cancer.

I think we’re already there, but now:

- How do we get into the communities where minorities are affected more or when cancer is deadlier for some of us?

- What are the comorbidities?

- What do we do?

- How do we go to these clinics and tell people your tumor should be tested?

- If you go to your local community hospital, you should get the same standard of care as if you’re going over to a university hospital. How do we educate them?

You see yourself as the ultimate advocate for others

Starting with working with students with special needs and being an advocate for small cell and lung cancer, period, I see myself as a fighter for the underdog. You have these voiceless populations.

At a recent checkup, I was down there talking with a gentleman who was there with his wife. They are a minority couple. She couldn’t handle the information. I said, “No, you need to ask them this, this, this, and this.”

It’s not like the people at their community hospital were trying to talk to them, like, “Oh, we’re just going to do this.” They were not really explaining anything to them. It sounded like they hadn’t even had tumor genetic testing done, but they were already treating it like they had a mutation. I’m like, “They never told you any of this?”

I’m becoming irate and enraged because regardless of who you’re talking to, you should have somebody, even a layperson, be able to explain it to anyone who comes into your hospital or clinic.

I have an example related to the follow-up for my breast cancer side effects from the radiation. When I first went to get the scans, the radiologists were like, “Oh, yes, you have dense breast tissue tissue,” which is common in African American women.

My OB-GYN doctor called me after she got the results. She said, “They might tell you that and tell you to come back in 6 months, but with your history, I would go see a breast surgeon.” Just like that.

Having a stereotypical mindset that it’s common, too, and you’re young, you’re an African American woman, [and] you have dense breast tissue. Just come back in 6 months, whatever. Not being thorough enough. I would not have known.

Inspired by Montessa's story?

Share your story, too!

Small Cell Lung Cancer Stories

Montessa L., Small Cell Lung Cancer

Cancer details: Small cell lung cancer

1st Symptoms: Chest pain, lingering cough

Treatment: Chemotherapy (Cisplatin switched to carboplatin, etoposide), chest radiation, brain radiation (prophylactic)

...